Introduction

Trees play an invaluable role in enhancing city environments, providing everything from energy savings to climate-change mitigation. But it’s important to remember that not all urban forests are created equal — and evaluating trees by their quantity as opposed to their quality is to display a fundamental misunderstanding of city trees’ potential worth.

Healthy, mature trees are exponentially more valuable than their newly planted, youthful cousins. Planting a tree without providing it optimal conditions for flourishing growth is to potentially deprive your community of the benefits — both environmentally and financially — gained when the tree reaches robust maturity. Why plant new trees every decade when you can properly care for one tree and nurture it to prosperous adulthood?

Let’s examine the ways in which mature trees offer advantages unrealized with immature urban forests.

Photo courtesy of Matthew Henry

Mature Trees versus Newly Planted Trees

As urban areas become more populated, city development — in the way of new residential and commercial infrastructure — often leads to the clearing of trees, with some forestry officials estimating urban tree loss at 36 million annually.

The most obvious method for combating this is to plant new trees as replacements for those being removed — on the surface, this makes perfect mathematical sense: subtract one tree, add one tree. The complication is that a newly planted tree offers only a fraction of the value of its larger, older counterpart.

By failing to provide new trees with the proper environment for healthy growth, we’re also failing to realize the benefits of mature urban trees; and indeed, this is precisely what’s occurring: in an urban environment, 50% of trees are removed or replaced before reaching ten years of age. And research suggests that a tree “replaced every ten years provides no meaningful ecological benefits as the tree never develops adequate leaf area.”

We need to rethink the way we assess and invest in urban forestry initiatives, even from a strictly economic perspective. Simply sticking a tree in the ground, with little concern for the often-inhospitable soil environment, is considered the cheapest way to reforest cities. But is it?

According to a study titled “The Benefits of Large Species Trees in Urban Landscapes”: “The Financial benefits of large species trees far outweigh the whole life costs associated with planting and maintaining them.”

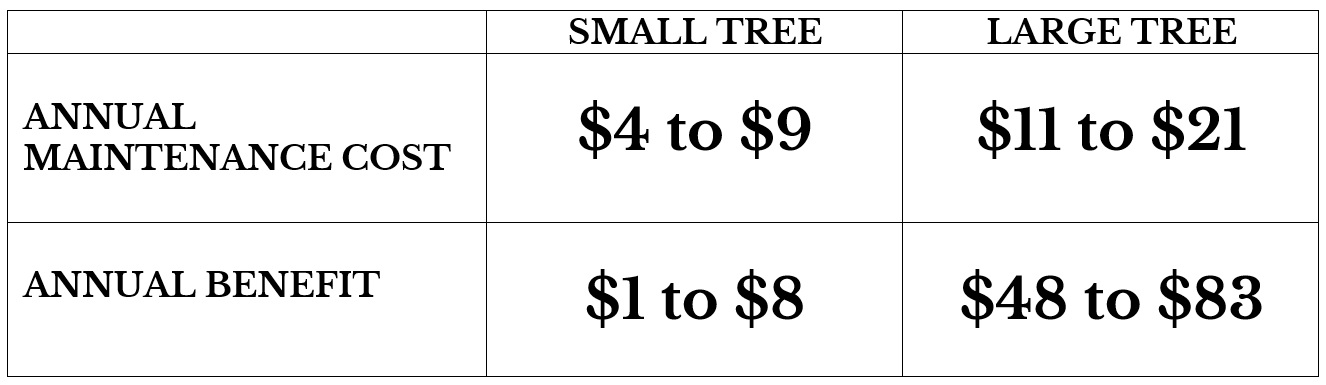

The study examined the maintenance and care costs of the trees versus their realized economic value — and the results are eye opening:

In other words, a large tree costs (on average) $16 annually to maintain and returns an average benefit of $65 — a four-multiple return on investment. On the other hand, a small tree costs about as much to maintain as it provides in value.

But what, exactly, are the specific financial and ecological benefits of mature urban trees?

The Tangible Benefits of Mature Urban Trees

The advantages of urban forests are well documented, offering residents a variety of health, community, and financial perks. But, while we often examine the benefits of city trees versus no city trees, it’s equally important to understand the benefits of mature trees versus newly planted trees.

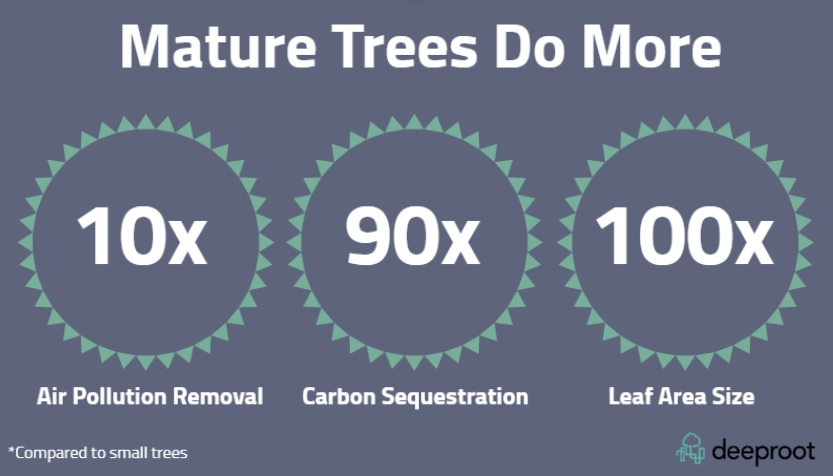

A City of Toronto study titled “Every Tree Counts” compared the environmental performance of a 6” diameter tree to a 30” diameter tree. The larger, mature tree was able to intercept 10 times as much air pollution, store up to 90 times more carbon, and possess a leaf area as much as 100 times the size.

Let’s explore in greater detail how these mature-tree advantages impact a city’s financial and ecological health.

CANOPY GROWTH

One of the primary ways in which mature trees offer significant advantages over smaller trees is their robust leaf canopy, a characteristic that leads to a litany of environmental and financial benefits.

Firstly, mature trees help mitigate the heat island effect, which occurs in shade-free city environments where the temperature rises above that experienced in outlying areas. According to the EPA, unshaded surfaces in these areas can be 20-25 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than shaded surfaces — and the air temperate can rise by as much as 9 degrees.

With a greater canopy area, mature trees provide shady respite from this dangerous condition. In tandem, community energy costs are also reduced: a study conducted on the financial benefits of green infrastructure (including tree canopy coverage) in Chester County, Pennsylvania, estimated an annual energy savings of $2.4 million.

Large, shady trees have other tangible health benefits. According to one study in which three rows of mature trees were planted outside an elementary school in Louisville, students “had increased immune system functioning and lower inflammation levels.” These health advantages have direct financial implications: “savings from health-related costs could be as high as 30 percent in Miami, 23 percent in New York City, and 19 percent in Los Angeles.”

Tree cover also, contrary to popular belief and as discussed in a previous blog, reduces community crime. Buildings with high levels of vegetation had 52 percent fewer crimes; likewise, a 10 percent increase in tree canopy coverage is associated with a nearly 12 percent decrease in crime.

AIR QUALITY

Mature trees are also far more effective at improving air quality and thus slowing climate change. As noted earlier, large trees can sequester up to 90 times as much carbon as can smaller ones; and, according to the USFS, a 30” tree removes 70 times as much air pollution annually than trees with a diameter of 3” or less.

The fundamentals of photosynthesis also work better with mature trees. Carbon dioxide is taken in by trees and turned into oxygen, which is released into the air. One estimate in Edmond, Oklahoma (population 90,000) calculated that 141,000 tons of oxygen are produced annually by city trees — and “the amount of oxygen produced increases with the size and health of a tree, and larger, older trees that are in better condition produce the most oxygen.”

WATER TREATMENT

City trees have the ability to assist with stormwater treatment, removing pollutants from street runoff before the water drains into the local waterways or sewer systems. Once again, mature trees are more effective in this function than smaller trees.

According to the EPA, “mature trees provide significant stormwater quantity and rate control benefits through soil storage, interception, and evapotranspiration. A tree with a 25-foot canopy and associated soil can manage the 1-inch rainfall from 2,400 square feet of impervious surface.”

This stormwater treatment efficiency also reduces a city’s reliance on grey infrastructure. By utilizing trees for a number of overlapping community functions, urban forestry can be better justified in the municipal budget.

COMMUNITY EFFECT

Finally, mature trees offer the community a series of additional, underappreciated benefits. To start, homes in tree-covered areas are proven to be worth more than those without canopy coverage (this leads to greater property taxes that can, potentially, be reinvested in healthy tree plantings). Shady urban areas, whether streetscapes or parks, likewise provide residents with places to gather for events or exercise, increasing the mental and physical well-being of the community. Large trees also serve as suitable homes for area wildlife, increasing the community’s biodiversity.

Some areas even embrace the historical heritage of their old trees — like the Treaty Oak in Austin, Texas. One of the oldest trees in the state, it predates European settlement with a lineage dating back over five centuries to the Comanche and Tonkawa native tribes. It remains a source of pride — and tourism — in the local community.

Hopefully the three new trees in the background will grow to the size of the mature tree in the foreground, offering the community all the benefits of large, healthy trees

Photo courtesy of Fons Heijnsbroek

Investing in Mature Urban Trees

So, what can we do to realize the advantages of large urban trees? The first thing we need to do is place greater value on our existing trees and their preservation.

Joe Coles, an urban tree campaigner, observes that “if we value green infrastructure to the same level as grey then large street trees will become far too valuable to lose. Until there is acceptance that large trees, taking decades to reach maturity, have significant value — a fact based on scientific evidence — we will continue to see spurious but convenient assertions that higher numbers of small replacement trees are adequate compensation to facilitate development.”

Secondly, when planting new trees, we must embrace a long-term approach. This means supporting the tree during its decade-plus road to maturity, rather than simply planting it anywhere and replacing it when it fails to grow. A major element in the success of newly planted urban trees is its access to quality, uncompacted soils — one of the chief advantages of the Silva Cell system.

In the end, urban forests thrive when we value quality over quantity. By embracing this strategy and investing in the future of city trees, we can improve our communities’ economic and environmental well-being.

Leave Your Comment