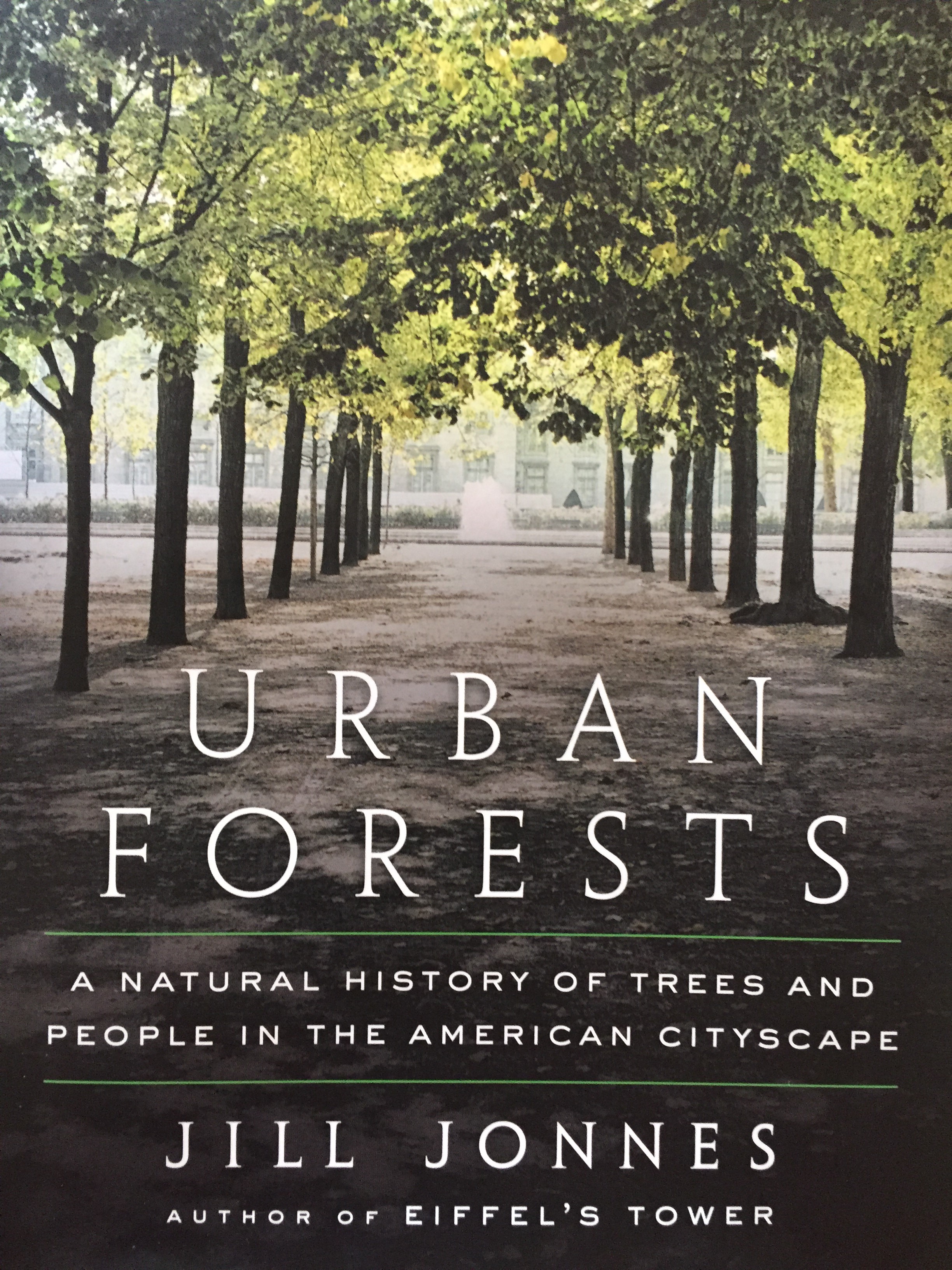

We have a long and complex history in our relationship to trees in the built environment. As our ancestors congregated in the “New World” they wanted to open up the canopy to let the light filter down and to be able to grow food. Then, as more people arrived and cities formed, trees were cut for housing, commerce, and to increase space for farming. As we were both cutting them down for open space and as we began building streets, we were lucky that some had the vision to realize the value of planting trees to improve the visual aspect along these mobility corridors. A recent book by Jill Jonnes, “Urban Forests: A Natural History of Trees and People in the American Cityscape” attempts to tell the story of this relationship.

Readers will find engaging stories of advocates like Eliza Scidmore, who worked for decades to beautify Washington D.C. with the blossoming Japanese Cherry Trees. They will feel the pain and helplessness as American Chestnuts, and later Elms and Ashes, are devastated by introduced pests. We are taken back to a time of active civics, like schoolchildren planting trees and the founding of Arbor Day.

Emotionally, the book delivers by communicating stories of the powerful relationship between humans and trees. Yet we wish Jonnes had given us a fuller understanding of the history of these trees. The story she’s trying to tell would be more compelling if she helped us understand how trees lived within the urban landscape such that they were so valued. Were they deliberately planted street trees? Parks trees? Heritage trees?

One quote does describe the trees as a part of the urban environment: “‘When you came into any town, … the landscape changed. You entered this kind of forest with 100-foot arches. The shadows changed. Everything seemed reverent, there was a certain serenity, a certain calmness.’ As the elms came down, ‘you started to notice the severity of things – the wires and utility poles, the cracks in the hot pavement, which no longer was bathed in shadows’” (pg 150). In general, however, the book lacked many of the details about city design – the decisions that were or weren’t made regarding the selection, placement, and role of these trees – that would have completed the picture of how the history of people and urban trees have influenced each other.

We read Urban Forests looking for the fullness of the lives of trees within the fabric of our cities, and we were left wanting more. The sub-title of the book tells us that Jonnes’ intent was to highlight how “The modern American city is a great place to look and learn about trees because this fundamentally unnatural environment has a far bigger variety of trees than any crowded real forest.” Jonnes convincingly describes how the monocultures of Chestnuts, Elms, and Ashes contributed to their demise. We learn about disease research, breeding for disease resistance cultivars, and replacement plantings. The lesson from this is clear and significant: we must plan for a diversity of trees in our cities if we want robust and mature urban forest. Jonnes provides abundant citations from primary sources of a number of poignant events, but they seem to crowd out a descriptive, overarching narrative of the trees as part of our cities.

While it was interesting to learn the details and personalities that were key to early tree losses in the Chestnut, Elm, and Ash tragedies, we also wanted to learn about forests covering other parts of the United States. For example, how were trees respected in cities that were populated as a result of the logging industry versus cities that were founded on farming in the Midwestern plains? How was the knowledge from Charles Sargent, John Davey, and John Muir carried West? The work of Frederick Law Olmsted certainly stressed the importance of green spaces for the health and enjoyment of city dwellers, but as the country grew westward did we consider space for trees in our initial city design?

Perhaps we came into Urban Forests with different expectations than the average reader.

As a Landscape Architect focusing on the public realm, Peg picked up this book with excitement to dive deeper into the urban aspects of trees. How are trees an active component of urban space? How can we enhance their implementation and how can we challenge the confines of retrofit infrastructure? Barbara wanted to learn more about the trees within our streetscapes as a meaningful part of our culture, and about trees as an increasingly utilized tool to address storm water management. We hoped for the very mechanics of creating a streetscape for healthy trees. We commonly look to Alliance for Community Trees, The Arbor Day Foundation, and Davey Trees for inspiration and innovation, and with that in mind, we searched for new guidance in Urban Forests.

We didn’t feel that we entirely found it, but acknowledge that Jonnes may be nudging us toward a new understanding of the urban forest as a tool for environmental benefit. From the National Urban Forestry Conference in 1982, she relates how “Rowan Rowntree had learned that the case for restoring city forests required a stronger argument than their mere beauty.” Jonnes discusses “looking at city trees with new eyes” to see how urban forests can be a low-tech solution to climate change. She highlights recent United States Forest Service and Environmental Protection Agency research identifying trees as part of green infrastructure and developing metrics to prove performance for air quality, heat, and stormwater.

As we skim back through our notes in the book, a timeline emerges: decades of ups and downs

for trees and urban development. Jonnes notes, “The threats to survival for a city tree have not changed substantially since Andrew Jackson Downing, the original tree evangelist, wrote in 1846: Trees ‘…are placed in a hole quite too small for them, a little rubbish is thrown about their roots…’” Jonnes also quotes National Arbor Day Foundation President Dan Lambe: “[I]t is a constant battle…But we’re also smarter and more connected as a community. We are making progress.”

What is this progress?

We are learning that trees for trees to mature to their potential they need to have space for their canopy and their root zone. There are competing interests for all space in cities and this is especially true along our rights of ways and in dense neighborhoods; if we cannot provide the surface space for medium and large trees then we need to invest in the below grade treatments that allow a tree to spread its roots for nutrients and supporting structure as they grow to their majestic form.

Research programs such as those at the United States Forest Service, University of California – Davis, University of Vermont, Cornell University, and University of Washington are gathering data to establish monetary values for urban trees adding air pollution, health, energy, and stormwater metrics to the aesthetic value. The Alliance for Community Trees is publishing these metrics and using social media to raise awareness of the value of our urban trees.

We must thank Jill Jonnes for choosing to author a book telling the story of our urban trees and the champions behind them. Jonnes closes noting that more Americans are opting for urban life and encourages politicians and city managers to become serious about “creating the lushest canopies we can nurture.” We see this in our own practice as well. It’s time to get to work.

Peg Staehli is Principal at MIG|SvR and a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects. Barbara Van de Fen is Project engineer at MIG|SvR.

Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

Leave Your Comment