Very often the “trees” that are added to architectural drawings or envisioned as elements of a new downtown landscape are only part of the structure: the aboveground portion that includes the trunk, the branches, the canopy, and the leaves. While this portion of the tree is usually the only visible part and thus captivates the human spirit more readily, it is inextricably linked to and impacted by its belowground portion, each adjusting and altering in accordance with the other.

As trees grow they occupy more space above and below ground, becoming a form of shelter as much as a gathering place in fields, forests, and city streets. The history of human culture and society is closely tied to trees in such a way that we cannot ignore their needs, especially those related to elements found underground. In Jim Urban’s words, “People have always gathered around trees, and that’s been true since time immemorial. The American colonists gathered around 13 trees to plot the revolution. It’s been a gathering place for all different cultures. It provides protective shading, protection from the rain, protection from the sun, and it’s just a natural place to be.”

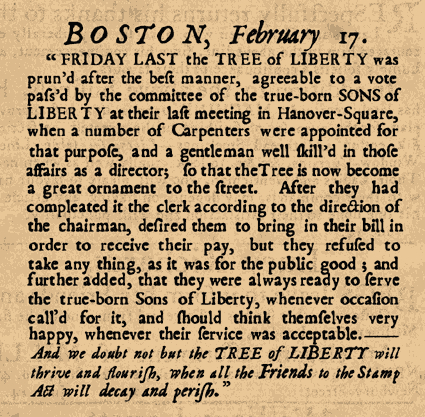

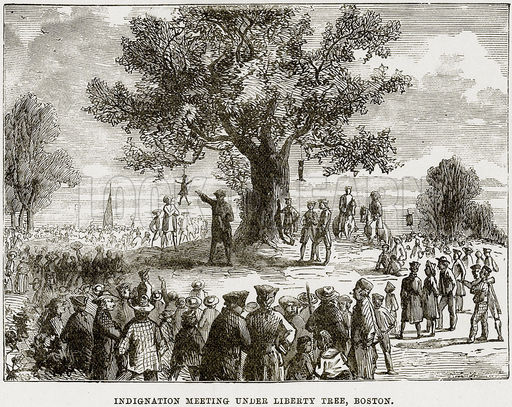

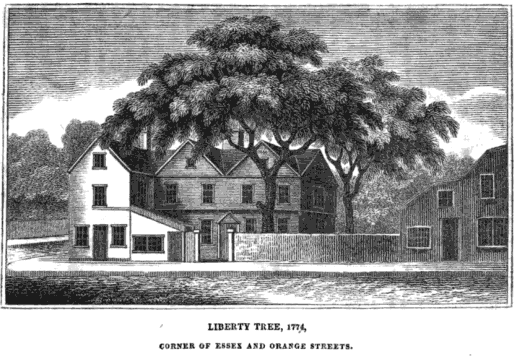

The trees Jim refers to that sheltered the plotting of the American Revolution trace back to one of the most famous trees in U.S. history – the Liberty Tree, a large elm tree in Boston that the early colonists would gather beneath for meetings and rallies. In 1872, historian George Preble recounted the history of the Liberty Tree this way: “The old liberty tree in Boston was the largest of a grove of beautiful elms that stood in Hanover square at the corner of Orange . . . and Essex streets . . . It received the name of liberty tree, from the association called the Sons of Liberty holding their meetings under it during the summer of 1765. The ground under it was called Liberty Hall. A pole fastened to its trunk rose far above its branching top, and when a red flag was thrown to the breeze the signal was understood by the people. Here the Sons of Liberty held many notable meetings, and placards and banners were often suspended from the limbs or affixed to the tree.”

The first act of defiance committed by the Colonists against the British took place in 1775 under the Liberty Tree in protest to the Stamp Act, where the colonists hung an effigy of Andrew Oliver (the man selected by King George III to impose the tax) from its branches. A few weeks later, a plaque was nailed to the tree with the inscription “The Tree of Liberty”.

Clearly threatened by the tree as a powerful symbol of independence, as well as its demarcation as a gathering place for the meetings of the Sons of Liberty, the British cut it down in 1775. The next day, the Essex Gazette reported, “Armed with axes, the British soldiers made a furious attack upon it. After a long spell of laughing and grinning, sweating, swearing, and foaming with malice diabolical, they cut down a tree because it bore the name of Liberty.” Despite its destruction, the tree continued to serve as a symbol for the colonists, as it was represented in their flags and memorialized in Thomas Paine’s 1775 ballad “Liberty Tree”. The idea of a tree functioning as a symbolic, political gathering place also spread to the other colonies such that during the revolutionary era, one could not find a colony on the coast without a tree named “Liberty”.

The oldest of these original Liberty Trees, at St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland, was cut down in 1999 after it was irreparably battered by Hurricane Floyd. This 600 year old Tulip Poplar had been ardently protected and preserved by the local citizenry of Annapolis for the preceding 224 years, and was taken down in a solemn ceremony only following consultation with a number of arborists who confirmed that the hurricane’s damage left it on the cusp of a massive structural failure.[1]

Clearly, the aboveground portion of a tree can have a tremendous impact for people and communities that can stretch, grow, and evolve for centuries. Despite this, the way we plan for trees in cities has little to do with how trees themselves grow, and everything to do with how roads, buildings, and utilities are constructed. But with an understanding of how trees mature, and what their structure is both above and belowground, we can create a hospitable and nurturing environment – and maybe one day change the course of history.

Top image credit: Shane Holden

Leave Your Comment