One of the most famous social science experiments of all time is the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment. This study, conducted in 1972 by psychologist Walter Mischel, examined the development of delayed gratification in children and the influence it had on their choices and success rates adults.

The study worked like this: Mischel put each child alone in a room with an edible treat (pretzels and oreos were also used, but for some reason marshmallows became the defining option). They were told that they could either eat the treat right away — or, if they were able to wait for 15 minutes, they would be given a second additional marshmallow as a reward.

It doesn’t sound all that hard, but especially for children, this is agonizing.

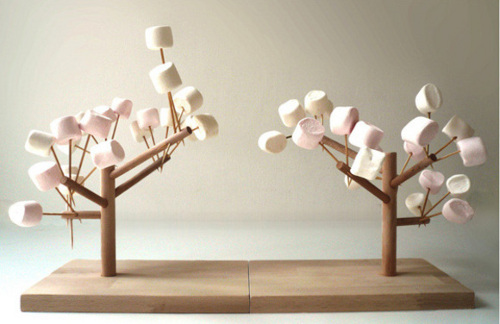

Delayed gratification is defined as the ability to wait to obtain something one wants. Every day we encounter situations in which we have to choose between delaying gratification or precipitating it immediately. Recently I started thinking about how this idea pertains to trees, particularly in urban areas.

Look at any architecture or landscape architecture renderings and you are sure to see beautiful trees. The trees are there for a reason: whether they realize it or not, people want to see trees on their streetscapes. They can’t help it; it makes them feel good. I can’t imagine an architect not putting trees on a sketch like the one below. It simply wouldn’t fly.

Sometimes real thought has been put in to the underpinnings of the design as they pertain to the trees on initial sketches like these, and sometimes it hasn’t. By the time final budgets have been determined, however, only a small percentage of plans include conditions necessary to grow the big, healthy and mature street trees represented in the original concept drawings. Instead, young trees are planted in difficult conditions, often with access only to the soil contained in their 4 x 4 cutout, and fail to thrive. They are replaced on a short cycle, an avoidable recurring expense and a missed ecological opportunity.

Designing a site that takes long-term tree needs into account and then waiting for them to grow to maturity is a little bit like Mischel’s experiment. It’s an everyday exercise in delayed gratification for designers and owners, albeit a very long one.

Almost every part of a development or redevelopment is at its best and most valuable when it is the newest. Materials are spiffy and clean, everything works as advertised (or is still under warranty), colors are bright and bold. Trees are the rare exception to this rule. Trees look better and better — and function accordingly — as they mature. They pay you back in spades, literally and metaphorically. From a landscape design perspective, they are the ultimate second marshmallow.

Walter Mischel’s experiment indicated that an ability to delay gratification as a child was a strong predictor of competence as an adult. Now, obviously there are limits to comparing the results of Mischel’s study with our practices for designing for street trees, but I think there are some important commonalities. We know definitively that our cities are more ecologically functional, enjoyable, profitable and healthy places when they incorporate mature trees. We also know that it takes a while to grow the mature trees that provide the majority of these benefits. I’d like to think that we possess the self-control to design and build our urban landscapes with that 50-year outcome in mind.

Marshmallow tree: Kim Vallee

Sketch: Townworks

Leave Your Comment