Getting funding for tree planting isn’t always easy. Still, it’s a piece of cake compared to getting funding for tree maintenance. Look at San Francisco, which is on the cusp of turning over the responsibility of their street trees to property owners.

Planting a street tree thoughtfully with regard to species, location and soil volume are all extremely important, but maintenance is a critical component of long-term success. Volunteers have long helped to fill in the gap between the needs of trees and the realities of budgeting, but even their good intentions are dwarfed by the number of trees needing care. I’ve long wondered about how can we encourage more volunteer efforts for this cause.

I’m not the only one. Christine Moskell, Shorna Broussard Allred, and Gretchen Ferenz recently published this study, “Examining Motivations and Recruitment Strategies for Urban Forestry Volunteers” to examine this issue further.This study explored the following questions:

(1) What are the motivations of urban forestry volunteers?

(2) What are the most effective strategies employed by urban forestry organizations to engage stakeholders?

(3) Do the engagement strategies used by urban forestry organizations match the motivations of volunteers?

To help answer question #1, study participants — who were either participating in a Million Trees NYC planting initiative or part of a focus group of urban forestry practitioners –were asked to self-report on their motivations for participating in the tree planting event. Their reasons included:

Environmental benefits of trees (30%)

Community service (23%)

Benefits to youth (20%)

Enjoyment from planting trees (20%)

The need for more trees (10%)

Attending the event as part of a school class (10%)

Other (17%) — for example, “church” and “inspiration”

I think it’s also worth noting that 80% of the volunteers were there as part of a group activity — either through a faith-based organized, community service, or a non-profit.

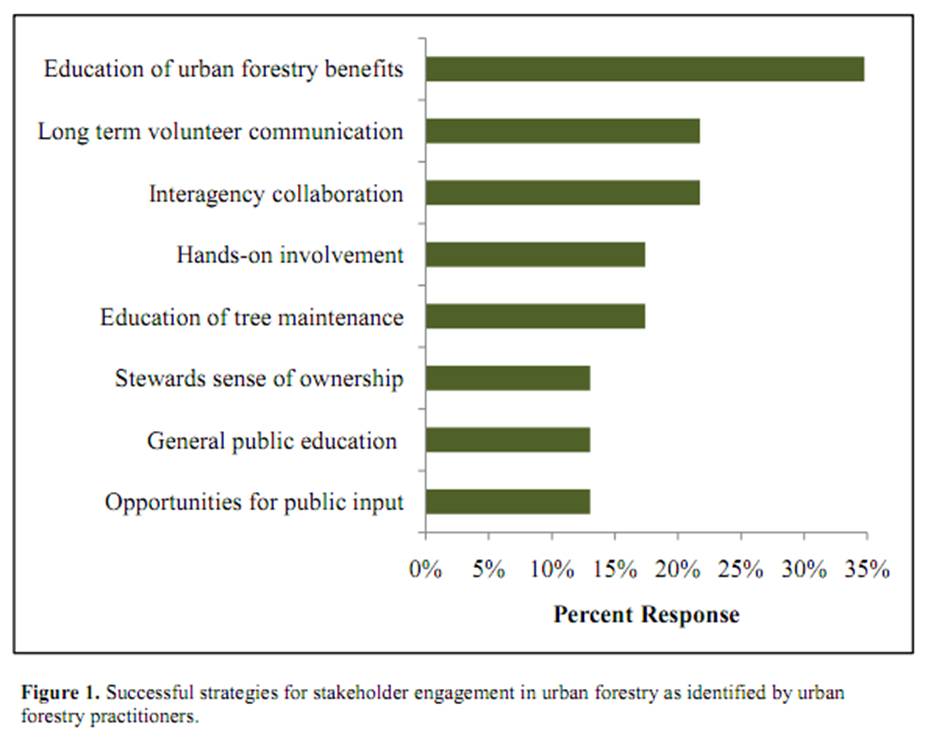

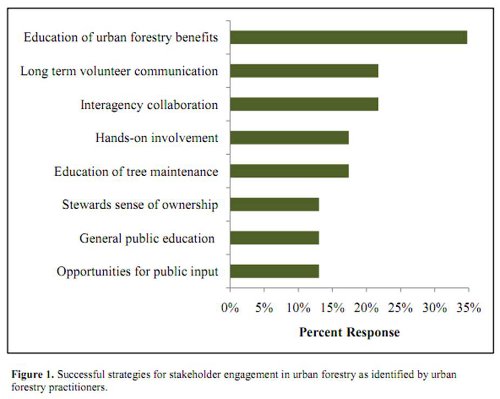

The main stakeholder engagement strategies used by urban forestry organizations (answering question #2, above) to promote this volunteer opportunity were:

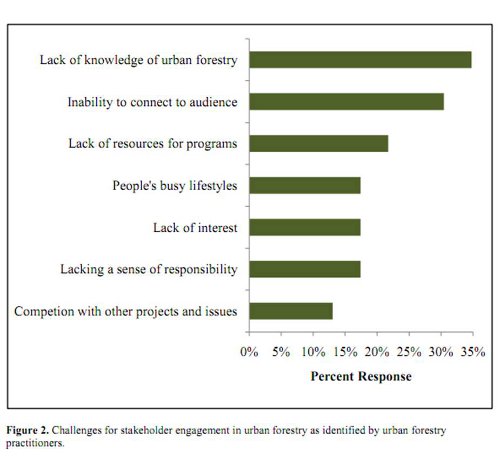

And the main challenges to those strategies were:

If you’ve already had some experience in non-profit or volunteer work, perhaps these findings won’t surprise you. The question of how to motivate and engage unpaid participants is something that all organizations with volunteers struggle with, and I am going to speculate wildly that the challenges they face are basically stable across different fields.

Now, the volunteers in this study were planting trees in a park, and at DeepRoot we generally concern ourselves with trees on streets and in other paved areas. What might the findings from this study mean for the role volunteers can play in their care?

The authors cite another paper in this study, by Gorman et al. (2004), that I explored in an earlier post. This paper found that “people’s values associated with street trees were dependent upon the presence of a street tree outside of their residence” (the emphasis is mine).

So we’re in a bit of a tangle. Urban trees across the country rely on volunteers for care and maintenance, but a primary challenge to recruiting new participants may be that they have not grown up in areas where there are surviving street trees. Planting more trees, everywhere, is a critically important goal that we support, but planting them in conditions suitable for long-term growth is even more important.

I don’t have any brilliant answers for building an army of citizen foresters, but this study is a great starting point for organizations that run volunteer tree care programs. A better understanding of the range of personal motivations for donating time to urban forestry projects will make the continual creation of satisfying opportunities for them attainable.

Leave Your Comment