A big shift in how stormwater is managed is occurring as more and more agencies begin planning and implementing green infrastructure to reduce volume and increase quality of stormwater runoff. While regional climate considerations, agency operations and maintenance practices, and the physical use of adjacent space (e.g. if the stormwater facility next to a road or sidewalk), all impact the design of a green stormwater facility, one of the most critical steps is developing a design detail that efficiently and effectively routes stormwater runoff into the stormwater facility. In urban and suburban environments along public streets, the design element that achieves this is an inlet design or drain curb cut.

While these may seem like relatively simple design elements, they become more significant when local context is considered. Is the site a retrofit to an existing street or new construction? Is the site on a local access street or a high-volume arterial? What is the adjacent land-use? How are people using the curb space and at what frequency? Recognizing and understanding the various conditions and contexts under which a curb cut may be installed can help us to understand how different components of a curb cut are important to its function.

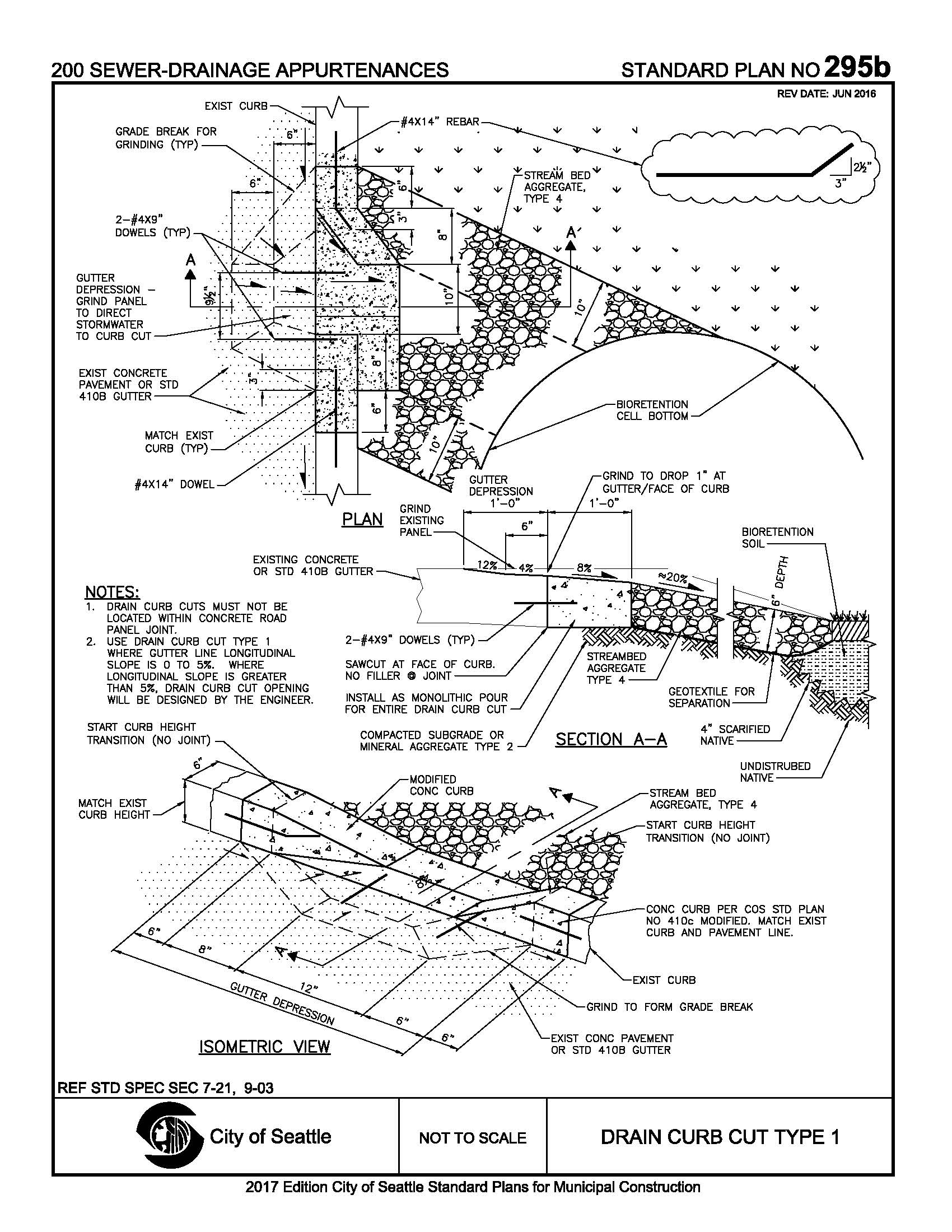

Let’s look at a standard detail from the City of Seattle (Standard Plan 295b – Drain Curb Cut Type 1) to see how each component of the detail is designed for performance. The primary goal of a curb cut is to direct runoff into a stormwater facility. Therefore, the horizontal and vertical alignment of the curb and gutter play important roles. In this detail Seattle incorporates a one-inch depression in the gutter combined with a modification to the alignment of the curb approaching the curb cut opening to redirect stormwater from the gutter through the curb cut opening. The width of the opening also impacts the amount of flow that will pass through the curb cut rather than bypass the curb cut depending on the speed of the water. This Seattle detail has a 10-inch curb opening plus an additional 8-inches for the modification of the upstream curb; this increased opening width also reduces the potential for debris to buildup at the curb face and block flow from entering the stormwater facility.

Once stormwater in the gutter has changed direction additional design elements reinforce the flow direction through the curb cut opening. In the Seattle detail, a small 12-inch concrete pad behind the original curb alignment slopes (8%) towards the stormwater facility to provide a one-inch drop followed by an even steeper slope (~20%) beyond the curb cut. One of the biggest maintenance items seen observing curb cuts in the field is sediment buildup and plant material at the curb opening that blocks flow from entering the stormwater facility. Reinforcing the slope through the entire curb cut and/or providing a physical drop at the back of the curb cut (such as Portland’s Typical Green Street Detail SW-330) helps to reduce bypass and maintenance.

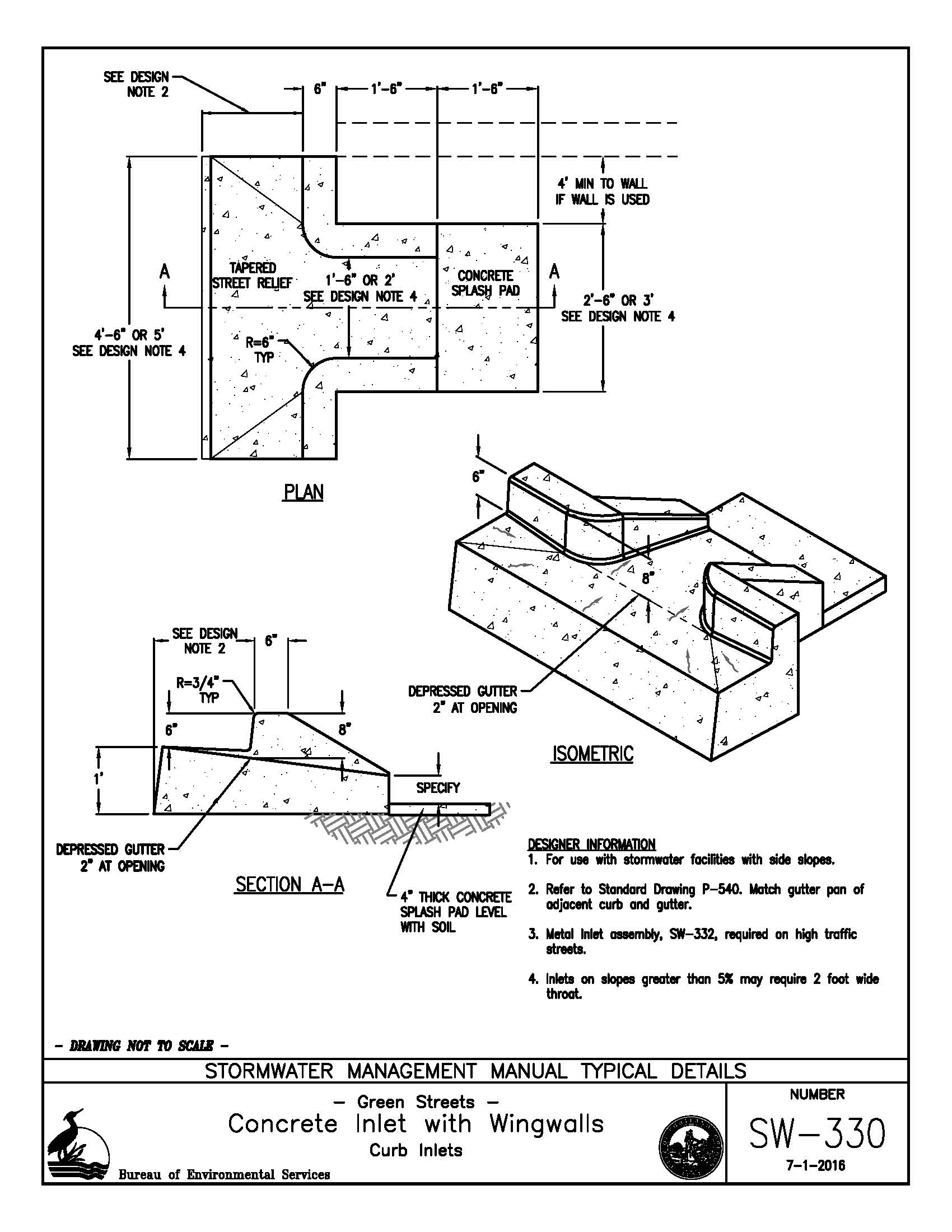

Once stormwater in the gutter has changed direction additional design elements reinforce the flow direction through the curb cut opening. In the Seattle detail, a small 12-inch concrete pad behind the original curb alignment slopes (8%) towards the stormwater facility to provide a one-inch drop followed by an even steeper slope (~20%) beyond the curb cut. One of the biggest maintenance items seen observing curb cuts in the field is sediment buildup and plant material at the curb opening that blocks flow from entering the stormwater facility. Reinforcing the slope through the entire curb cut and/or providing a physical drop at the back of the curb cut (such as Portland’s Typical Green Street Detail SW-330) helps to reduce bypass and maintenance. Other design elements should consider how the detail helps to slow flow velocities, reduce erosion, and allow for sediment capture. The Seattle detail shows stream bed aggregate angled towards the bottom of the facility (rather than perpendicular to the curb) to align with the flow path of the runoff. The cobble bottom helps to provide space for sediment and debris capture, reduce flow velocities, and provide better long-term function at the curb cut. The Portland detail on the other hand has concrete wing walls that direct flow perpendicularly into the stormwater facility and a concrete pad at the back of the curb cut to address erosion concerns. The variations in design approach result in a more natural appearance with Seattle’s detail and a more structural appearance with Portland’s detail.

Other design elements should consider how the detail helps to slow flow velocities, reduce erosion, and allow for sediment capture. The Seattle detail shows stream bed aggregate angled towards the bottom of the facility (rather than perpendicular to the curb) to align with the flow path of the runoff. The cobble bottom helps to provide space for sediment and debris capture, reduce flow velocities, and provide better long-term function at the curb cut. The Portland detail on the other hand has concrete wing walls that direct flow perpendicularly into the stormwater facility and a concrete pad at the back of the curb cut to address erosion concerns. The variations in design approach result in a more natural appearance with Seattle’s detail and a more structural appearance with Portland’s detail.

Best practices for conventional stormwater facilities (i.e. gray infrastructure systems), such as ponds and vaults, have clear design requirements to provide presettling. Presettling allows space for sediment to settle at the entrance of a facility and a dedicated place where more routine maintenance is expected. Design considerations for presettling at curb cuts, such as for bioretention cells along a roadside, is still evolving; however, observations indicate designs should be dictated based on the contributing drainage areas and to some extent the land use (e.g. streets with higher traffic volumes, arterials streets, have more sediment and pollutants). The City of Seattle has recently modified their design requirements and do not require a dedicated presettling cell along low volume local streets but recommends that a portion of a first bioretention cell create a presettling zone, and that downstream cells, with smaller contributing areas, are ok without presettling.

Additional elements that impact design decisions but focus on non-stormwater elements include:

- Construction type: many green infrastructure projects in the public right of way are retrofit projects so it is important to understand how construction of a detail will be carried out and to what extent the detail is practical. Consider talking with a local installer to understand limitations that may exist as you work through detailing your own projects.

- Covers across curb cuts: Depending on street context design considerations may also include providing a cover across the curb cut (insert image). The inclusion of a cover can limit car tires from rolling into/through the curb opening. Structural engineering may be needed to address design, constructability and cost considerations if the goal of a cover is intended to stop a car from rolling through the curb cut. When a curb cut is adjacent to an area used by people walking a cover may also be desired to address pedestrian access goals along parking zones and other locations where foot traffic can be expected along the curb line (the width of the cover and adjoining pavement should be evaluated for pedestrian use).

- Operational and maintenance requirements: Designs should consider the type and approach of maintenance crews to understand the tools and materials that will be used to clear curb cuts and remove debris (e.g vactor trucks vs. shovels). Is the curb cut opening wide enough for the typical shovel carried by maintenance crews?

- Urban design and aesthetics: Land use and how the right of way is used should be considered. Some details use significantly more concrete to reduce long-term maintenance but as a designer we must consider how the number of curb cuts along a street may stand out within varying street contexts. For example, how will the character and feel of a residential street with a planting strip vary from an arterial street with more commercial land-uses with a dozen or more new concrete curb cuts?

As you can see there are a variety of elements to consider when designing a curb cut in the public realm. The NACTO Urban Street Stormwater Guide is a great resource for additional discussion related to curb cut or inlet design. Remember to consider both the stormwater and non-stormwater uses during design as subtle changes to the detail can help to facilitate stormwater goals, simplify maintenance, and improve access for the various users along a street.

Nathan Polanski is a civil engineer with MIG | SvR.

Alexey Kljatov / CC BY-NC 2.0

All other images courtesy of MIG | SvR

Leave Your Comment