Introduction

As the sun blazes on another hot summer day, the thermometer on the east side of town is likely to display the same number as its counterpart three miles west — but this doesn’t tell the whole story. The way we experience heat, particularly in developed urban areas, is influenced by a number of environmental factors: heavily paved areas with little available shade can be up to 13 degrees hotter than those with cooling greenery.

And these heat island districts are not randomly distributed: decades-long discrimination patterns have ensured that lower socioeconomic neighborhoods are more susceptible to these uncomfortable, often life-threatening conditions.

So, what can be done? It’s crucial that we prioritize equal access to the positive benefits of tree coverage and urban green spaces. And, while the troubling socioeconomic discrepancy has been acknowledged for years within the green infrastructure community, policymakers are finally beginning to address this disparity with new initiatives and unprecedented funding.

Less affluent communities are statistically less likely to have healthy, beneficial tree coverage.

The Disparity

American Forests, the oldest national nonprofit conservation organization in the United States (founded in 1875), unveiled their innovative Tree Equity Score tool in 2021. The score examines “socioeconomic status, existing tree cover, population density and other information for 150,000 neighborhoods and 486 metropolitan areas to determine whether locations have enough trees to provide optimal health, economic and climate benefits.”

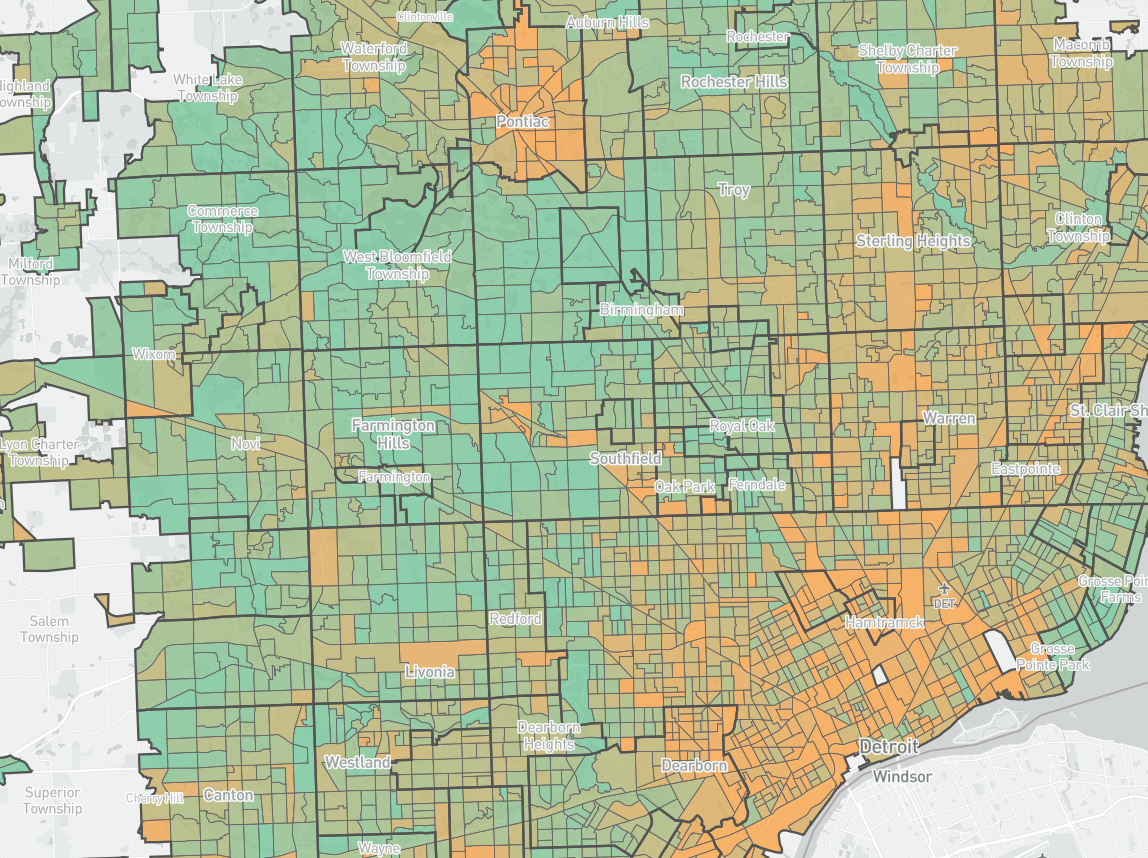

The initial report cited the large-scale cities with the “most benefits to gain” from rethinking their urban forestry planning, with Chicago, Columbus, and Detroit topping the list. The study also identified a consistent pattern across U.S. metro areas: communities of color and those with higher poverty rates had less access to tree canopy coverage than whiter and more affluent neighborhoods:

TES [Tree Equity Score] documents trees are sparsest in under-resourced neighborhoods and more prominent in wealthier, often whiter communities. The findings confirm a disturbing pattern of inequitable distribution of trees that has deprived many communities of color of the health and other benefits that sufficient tree cover can deliver. Neighborhoods with a majority of people of color have 33% less tree canopy on average than majority white communities. And neighborhoods with 90% or more of their residents living in poverty have 41% less tree canopy than communities with only 10% or less of the population in poverty.

There is a broader historical reality reflected in this data: the practice known as “red-lining,” dating back to the 1930s, systematically deprived lower-income neighborhoods (and their residents) of resources readily available elsewhere — everything from housing and insurance to neighborhood amenities, like conveniently located grocery stores, were viewed as “poor investments.”

Equitable tree canopy coverage is a symptom of the institutionalized red-line effect. As observed by the Star Tribune’s examination of Twin Cities urban forests: “Neighborhoods with the fewest trees were in the same areas where discriminatory lending practices had segregated people of color and freeway construction had plowed through Black neighborhoods. Communities with abundant tree cover had not been touched by those segregation policies or massive infrastructure projects that uprooted entire communities.”

Tree coverage in Detroit, like many metro areas, thrives in the suburbs while suffering most in the heart of the city.

More Than Just a “Tree Moment”

The good news is that tree advocates, government officials, and local policymakers are starting to recognize the urgent importance of environmental justice — and they’re taking action. Experts like Dan Lambe, chief executive at the Arbor Day Foundation, are optimistic about these initiatives:

City trees are not just having a moment. In many ways, this is more than a moment in the sun. This is, I believe, the new normal. [Trees are] not just a nice-to-have, they’re a must-have.

One of the primary reasons for enthusiasm is the recent passage of Inflation Reduction Act. Over the ten-year rollout timeline of the plan, a total of $1.5 billion has been earmarked for urban forestry with a “focus on underserved communities.” As Fortune Magazine notes: “Urban forestry advocates, who’ve argued for years about the benefits of trees in cities, see this moment as an opportunity to transform underserved communities that have grappled with dirtier air, dangerously high temperatures and other challenges because they don’t have a leafy canopy overhead.”

While the details of this funding’s specific distribution are still unfolding, the Biden administration has instituted the Justice40 campaign, which aims for 40% of federal investments to target “disadvantaged communities that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution.”

The IRA legislation comes at a turning point in the global fight against climate change. Decades of inactivity and political paralysis have worsened not only the climate crisis itself but also the disparity of who bears the brunt of a warming world. But federal action, as indispensable as it is, must couple with local officials and advocacy groups to execute the lofty ideals of environmental justice. Cities across America are implementing plans for city tree equity, often working in tandem with organizations like Frogtown Green: a residency group that educates landlords and property owners in the rent-heavy St. Paul neighborhood about the financial benefits of trees.

It’s also important to recognize the critical role played by soil, both its quality and quantity, in growing large trees (and thus, beneficial canopy coverage). While dense urban areas are often challenging environments for tree growth, there are plenty of available tools (including Silva Cells) for municipalities who choose to prioritize green space in their underserved neighborhoods. Many cities have instituted soil volume standards, a strategy that ensures the expansion of tree coverage in concurrence with the required soil volume being made accessible to each new public-realm tree. Maple Ridge in British Columbia is one such success story.

Maple Ridge in British Columbia has prioritized green spaces throughout the city, and their soil volume mandate has helped them achieve their canopy goals

Cautious Optimism

There is reason for optimism: priorities are shifting on both a federal and local level, presenting an unprecedented opportunity for tree canopy coverage growth and true environmental justice in metro areas across the country. But we’re still in the early stages of the enactment process — and the results are pending. Concerned citizens can always, however, stay informed about their communities: the Tree Equity Score tool is available for everybody to use, serving as a great instrument for monitoring the progress of these initiatives.

Leave Your Comment