All across the globe, it has been getting ever hotter with each passing year. With this heat comes serious health risks, including severe heat exhaustion and poor air quality, which disproportionately impact children, those who are ill, and the elderly. Heat-related impacts also disproportionately impact poor and minority communities, which tend to have less access to green space, and therefore have unequal access to the benefits those spaces provide.

Just how much less access? A study conducted by Bill Jesdale, et al in 2013 discovered that non-Hispanic blacks were 52% more likely, non-Hispanic Asians 32% more likely, and Hispanics 21% more to live in heat risk-related land cover (HRRLC) conditions compared to non-Hispanic whites. The disproportionate amount of risk to these populations is more than an unfortunate fact – it’s a serious issue of environmental justice. Why do these discrepancies occur? How can we move closer to equity?

The primary cause of HRRLC conditions is a lack of trees, and an overall lower percentage of canopy cover in affected neighborhoods (heat risk-related land cover is just one type of health risk associated with lower tree canopy cover). Several studies have shown that low-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods with large minority populations have statistically fewer trees than wealthy areas and predominantly white neighborhoods. For example, in Los Angeles, tree canopy covers range from 3% in downtown to more than 50% in Bel Air-Beverly Crest. Data revealed that Los Angeles’ “tree-poor” neighborhoods also tended to be its financially poor neighborhoods. Los Angeles is just one example of many. Poorer communities across the board are less likely to have trees, while richer communities not only have them but are often named after them. This condition is so prevalent that it can even be seen from space.

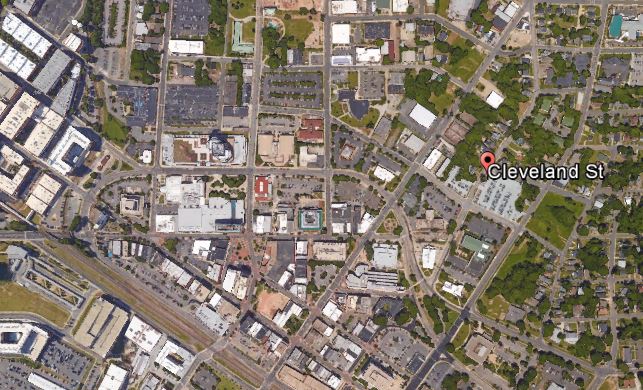

The Cleveland-Holloway neighborhood in Durham, NC is predominantly black and the urban tree canopy cover hovers around 10 percent.

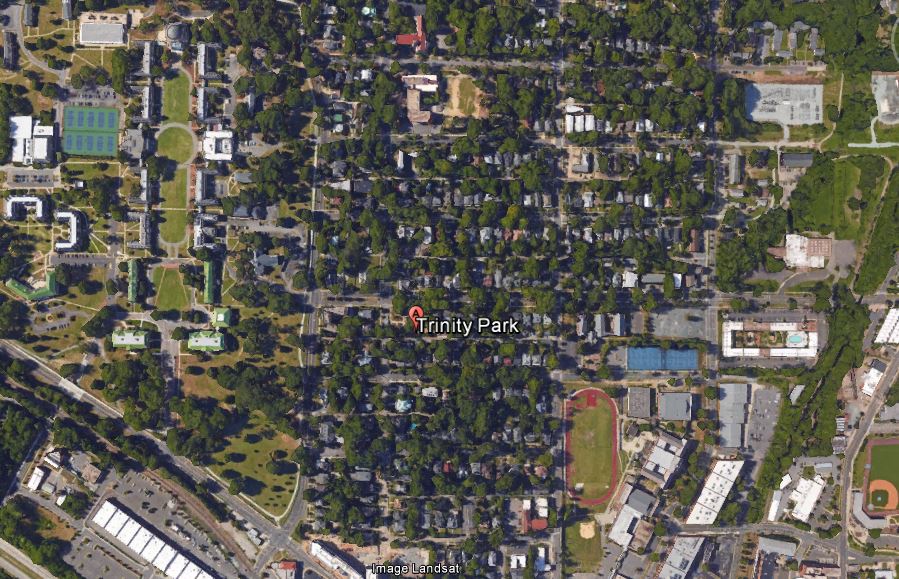

The Trinity Park neighborhood in Durham, NC is predominantly white and has more than 50 percent urban tree canopy cover.

Within each racial group, HRRLC conditions increased with increasing degrees of metropolitan-area level segregation. Land cover was associated with segregation within each racial/ethnic group, which may be somewhat explained by the concentration of these groups into densely populated neighborhoods, located within larger and more segregated cities. Jesdale’s study also found that in metropolitan regions with greater levels of racial segregation, everyone, including whites, is more likely to live in HRRLC areas. This may indicate that integrated metropolitan areas perform better at mitigating heat for everyone. Jesdale says, “When you have an area that’s more racially stratified, where race really dominates how people live with each other, there’s less shared investment, people are not as concerned with the common good. And that shows up in trees.” Segregated places like these may be less likely to make collective investments, which are often the drivers of environmental improvements for entire communities.

Well-meaning tree planting programs may unintentionally increase the discrepancy in tree cover between neighborhoods. Many programs operate by having residents request trees, and while this may increase the overall tree canopy in a given area, it does not necessarily put trees where they are needed. On the contrary, wealthier residents are more likely to have access to information about these programs, thereby increasing participation in this demographic. Meanwhile, a poorer resident may wish to participate, but may not know about the program. Residents in poorer areas are also more likely to rent, and therefore have less say about the environment that surrounds them. Other challenges include local policy and funding availability, and practical factors such as the physical availability of tree planting sites in underserved communities.

What can we do about this? There’s a lot more to it than I can cover in a single blog post, but here are a few things.

First, designers, policy makers, and planners need to be aware of what environmental justice is – and how it applies to their work. Careful thought should be given at every level to how the processes used to determine tree planting locations impact communities. What barriers are at play that may be influencing this – and how can those barriers be overcome?

How the landscape plays a role in justice and equity appears to be getting increased attention – at the recent American Society of Landscape Architects national meeting in October, 68 percent of the award-winning student designs focused on issues around environmental and social justice. I hope this shift toward understanding issues of environmental justice, and using listening and professional practice to come up with new approaches to meeting the the needs of communities, is underway across all urban design professions.

References

Badger, Emily. “The Inequality of Urban Tree Cover.” CityLab. N.p., 2013. Web. 01 Dec. 2016.

Dadigan, Marc. Jan. 13, 2011 Web Exclusive Print Share Subscribe Donate Now. “Tree Equity.” Tree Equity. N.p., 2011. Web. 01 Dec. 2016.

De Chant, Tim. “Income Inequality, as Seen from Space – Per Square Mile.” Per Square Mile. N.p., 2016. Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

Hudnall, David. “In Durham, Rich Neighborhoods Have Plenty of Trees. Poor Neighborhoods, Not So Much.” IndyWeek. June 8, 2016. Web.

Jesdale, Bill M., Rachel Morello-Frosch, and Lara Cushing. “The Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Heat Risk–Related Land Cover in Relation to Residential Segregation.” Environmental Health Perspectives 121.7 (2013): 811-17. Web.

Watkins, S. L., S. K. Mincey, J. Vogt, and S. P. Sweeney. “Is Planting Equitable? An Examination of the Spatial Distribution of Nonprofit Urban Tree-Planting Programs by Canopy Cover, Income, Race, and Ethnicity.” Environment and Behavior (2016): n. pag. Web.

Leave Your Comment