After finishing college in 1973, James Urban and his wife, Bonnie, enlisted in the Peace Corps. They were stationed in Iran, where they lived until 1975. Jim worked for the state planning office in Masshad, designing small parks and doing city planning for small cities with populations below 30,000.

His work brought him back and forth between these small towns and the large city of Masshad, and he was captivated and surprised by the quality of the street trees that he encountered, which were thriving with seemingly little effort, in the dry, desert soil. Upon closer inspection, he learned that these prosperous trees were flourishing because of an ancient irrigation system that uses Qanats, which was developed in Iran (Persia) 3,000 years ago.

In the video interview below, Jim recalled what he learned about how they were built:

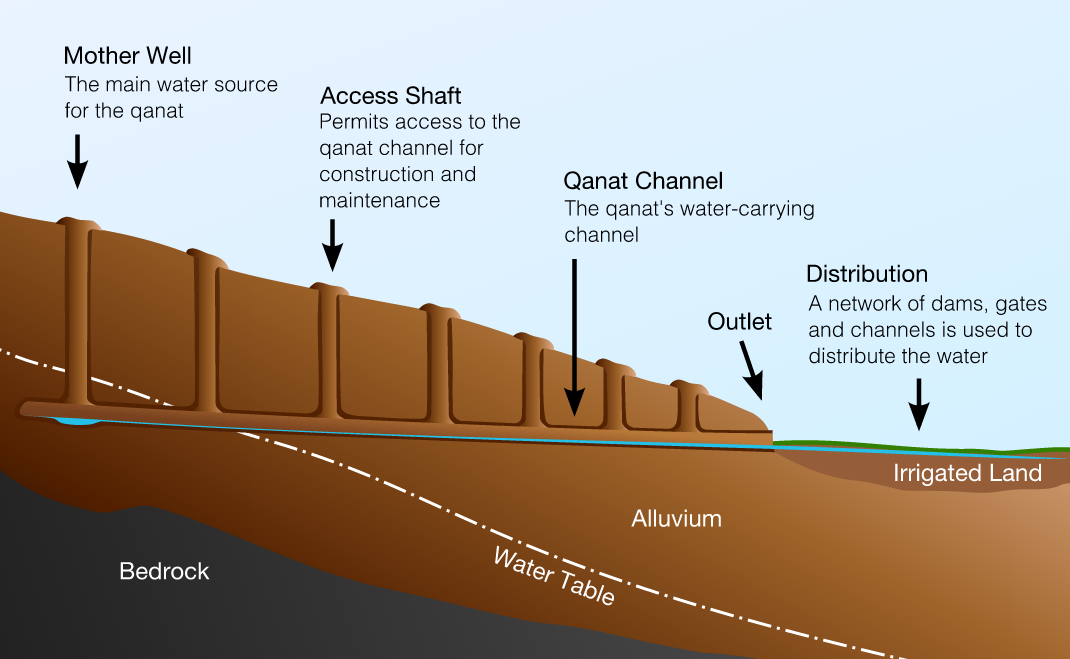

“They build these tunnels into the mountain that are called Qanats; some are 2-3 miles long. The water seeps out into the gardens of those who live at the top of the hill. Then the water comes out and cascades through network of channels called Jubs that line all of the streets. Their main purpose is to provide water to the town. So the surface water flows through the Jub, which also acts as a sewer. All along the Jubs are planted trees. And some of the Jubs stretch out into the desert, aligned by trees the whole way. And once the Jub stops, the trees stop.”

The Qanat works were built on a scale that rivalled the great aqueducts of the Roman Empire. But unlike Roman aqueducts, which now are relics of the past, some Qanats are still in use today. They are one of the most ecologically balanced water recovery systems available for desert regions, because they rely completely on gravity to transport the water from the source, exploiting the natural gradient of the land in order to transport the water underground to the agricultural areas below. In Iran alone there are 22,000 Qanats spanning more than 273,000 kilometers of subterranean channels, with trees lining every Jub that emerges from their outlets.[1]

Systems of Qanats proved incredibly successful in Iran and throughout other arid and semi-arid regions, including Jordan, Syria, Afghanistan, Cyprus, Spain, Peru, Chile, and Mexico. But their use has, as you might expect, gone into decline since the second half of the 20th century due to the introduction and widespread use of the pumped tube well[2]. Such wells offer advantages over Qanat irrigation by making it possible to bring water to the surface on command – but over-pumping has led water tables to fall, and aquifers to be depleted. Research and efforts are underway, however, to restore the Qanat system in arid regions, and the impact on trees is part of the puzzle. A 2002 survey paper regarding Qanats in Syria includes the following:

“Not only are Qanats relics of a prosperous past, but also sustainable and environmentally friendly systems of extracting groundwater. In Qarah, Syria, we have seen that combining ancient Qanats and modern drip irrigation systems for fruit trees might prolong the life of some Qanats and encourage younger generations to commit to their upkeep. Another option to think of is to encourage eco-tourism based around Qanats to provide alternative income for the farmers.” [3]

In Iran, focused efforts are now underway to promote, recognize, and restore the Qanat system via the establishment in 2005 of the International Center on Qanats and Historic Hydraulic Structures. This center, formed via an agreement of the government of Iran and UNESCO, facilitates research, training, transfer of knowledge, and preservation efforts regarding Qanat technology to fulfill sustainable development of water resources[4].

The close relationship between trees, plants and people, as expressed in their mutual reliance on Qanats as a source of their water, had a large influence on Jim’s future work that evolved slowly over time. Upon his return from Iran, he began working at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in Chicago. “The ideas of how the Iranians designed with trees and water started to appear in these projects first as merely an expression of the physical features such as juxtapositions of tree and water, or the use of rills and Islamic influenced forms, without understanding the function or science behind the forms,” he says. “Only much later did I begin to realize the reasons why the forms evolved.”

Perhaps the revelation that the Qanats of Iran played a hidden role in the design of some SOM projects will lend a hand in the effort to revitalize and promote their restoration. Or at least spark an interest for young designers worldwide to begin learning more about these innovative and sustainable systems.

Watch Jim talk about his time in Iran here.

[1] “Technology and Religion: The Qanat underground irrigation system”, Mohammad Reza Balali & Josef Keulartz

[2] Balali and Keulartz explain further that the shift toward pumped tube wells and away from Qanats was also encouraged as a result of the Land Reform Act of 1962-1966. This act involved the breaking up of large estates and redistribution of the land to the peasants, whose holdings were too small to maintain the Qanats.

[3] “Renovation of Qanats in Syria”, J. Wessels and R.J.A. Hoogeneen.

[4] International Center on Qanats and Historic Hydraulic Structures

Qanat cross section: Samuel Bailey /CC BY 3.0

Jub: Photo by V /CC BY-NC 2.0

Leave Your Comment