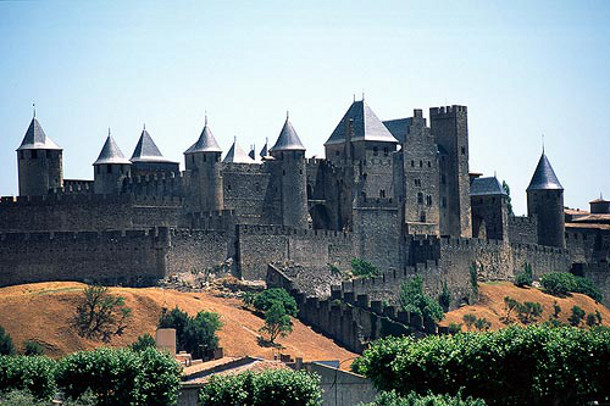

The fortified city of Carcassonne in southern France. Few citadels like this remain in Europe; if they were important, cannons demolished them. Carcassonne evaded this fate because a treaty in the 1600s made it a part of France, no longer a city/state, and its borders were moved hundreds of miles away. Image: France This Way

Read Part I of The History of Street Trees here.

In the United States we have hockey season, football season, etc. Well, in the Middle Ages of Europe there was a war season. It was after the fields were sowed and through the summer until harvest. Lords (i.e., kings) would round up farm boys and tried to take over the next kingdom twenty or thirty miles away. Wars were constant; everybody was attacking everybody, all the time. Paraphrasing Thomas Hobbes, a man’s life in Europe in that era was “nasty, brutish, and short.” This amount of warring in Europe led to lots of defensive and offensive innovations in cities. Perhaps you can see why there wasn’t a lot said or done about street trees in Medieval Europe. So how did Europe, which is now famous for its thousands of tree-lined walkways, get to be that way?

Many large European cities were circumvented by tall defensive stone walls, and their entire population either lived inside the fort, or lived outside and would flee inside at the approach of a marching army. These cities were independent entities or city/states responsible for their own defense. Human powered bows and arrows, spears, and other weapons were largely ineffective against their tall stone walls. Even siege machines like the trebuchet flung missiles over the city walls, not through them.Building large stone and mortar walls around the perimeter of a city was an effective form of defense, but was very expensive. Like today, municipal budgets were not what they should be, and cities had to be financially self-sustaining. I am sure extra stone wall construction was vetoed out of many a medieval city budget. To reduce the monetary outlay, perimeter city walls were made as short as possible. Inside the walls, buildings were squished together tightly to save money as well. This was done to the point that upper floors might be cantilevered out over streets, often within arm’s reach of one another. In these compressed environments there was no room for street trees. However, rapidly-growing trees such as Poplars were grown on the fort walls to have a ready supply of wood for quickly constructing palisade walls in case of breaches. These logs were cut to length, sharpened at the ends, and stood up vertically – think wooden forts in old western movies.

Around 1450 A.D., the importation of gunpowder from China and the perfection of casting metal cannons made walled cities obsolete because they could not withstand an onslaught of this new weaponry. Stone-and-mortar walls are brittle in the face of iron balls hitting them at several hundred miles per hour, and in rapid succession. Two things ended up happening to these previously impenetrable stone walls.

Of those walls that remained standing, some ended up being planted with trees (yes – trees planted on tall stone walls!), and became strolling promenades for the wealthy. For those of us who live in cold climate cities, think of this as a kind of early renaissance skyway system. These elevated walkways offered nice breezes for pedestrians, up and away from the smells of the city.

Here trees have been planted on the star bastions. Now mature, they mask their original military intent. The rise of the sovereign state and diminishment of the city/state gave rise to the unfortified modern grid city with street trees. Image: Natural Building Blog

Of the walls that came down, sometimes their stones were reused to build new special-purpose, star-shaped forts with bastions at each point. These star forts were low and wide, made from rammed earth and stone, and later brick, and their geometry was based solely on eliminating blind spots during battle. These earthworks dwarfed the scale of medieval walled cities and their great distances were used to disadvantage attacking cannons, which had to enlarge in order to lob ever-larger missiles. Inside the fort, it was critically important to move cannons quickly from star bastion to star bastion, so buildings were laid out in gridded blocks or center starburst patterns with roundabouts to facilitate the rapid deployment of heavy, horse-drawn cannons. Cannons are large and unwieldy, and combined with the carts that carried them, they weighed hundreds to several thousand pounds (kilos) each. They needed well-built, hard street surfaces that were wide and straight, rather than narrow and wiggling, in order to move around quickly and easily.

So those old, original stone walls that surrounded medieval cities were, unexpectedly, the precursors of two places for allées of trees: city walls and city streets. This is reflected is the etymology of the word the boulevard – defined as a tree-lined street – which was taken from the Dutch word Bolwerk (bastion), which became boloard and in 1435 became boulevard.

I’ve often said that I’m planting trees for my children. In medieval times, of course, tree planting and tree care was a luxury. Almost no regular guy would ever consider it, no matter how many times his wife might ask him. But trees did become useful in the context of defense, which is why old city walls and the bastions of star-shaped forts were first planted with them. Later, trees planted on walls were used for pleasure walks (think of New York City’s High Line). Similarly, trees that were planted on star-shaped forts that had originally been designed for cannons created streets with plenty of room for comfortable leather sprung leisure carriages, and trees to shade the promenading passengers and pedestrians alike. The street tree had arrived!

L. Peter MacDonagh, ASLA, is the Director of Science + Design at The Kestrel Design Group.

Leave Your Comment