A natural forest depends on a variety of partnerships between plants, animals, fungi and micro-organisms. An urban forest depends on a similarly complex series of partnerships, albeit mostly between humans.

Many biological factors affect the survival of an urban tree. I want to compare two studies involving community forestry programs about young urban tree establishment and survivability – one in Sacramento and one in San Francisco – to help uncover some of the trends in human behavior that impact the success of planting programs. What affects whether trees planted through these programs survive or not? Some of the results might surprise you.

Photo courtesy of SMUD.org

Sacramento Tree Foundation (Sacramento, CA)

The Shade Tree Program is a partnership between the Sacramento Tree Foundation (STF) and the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD). Residents or property owners (a.k.a. “shade-tree customers”) can receive up to 10 free trees if they agree to plant and maintain them. All customers receive a pre-planting, on-site consultation (15-45 minutes) with a community forester from STF for guidance on species selection, and tree placement and maintenance, before signing a Tree Care Agreement. Trees are delivered growing in 5-gallon containers. Customers are then supposed to plant the trees themselves in the locations determined during the STF consultation. No follow-up contact is required after planting, although customers can call STF for advice or take any of their free workshops.

Researchers from the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management at UC Berkeley and the USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station in Philadelphia studied the survival among young trees given away via the Shade Tree Program. Their findings, summarized below, were published in 2014 in the Journal of Landscape and Urban Planning.

Researchers selected a random sample of 436 trees out of the nearly 14,000 delivered by STF in the year 2007 and monitored them every summer from 2008 through 2012. The sample included about 30 species. Trees were well-distributed around the city of Sacramento and surrounding areas.

15% of the 436 trees delivered were never planted, according to field observations and customer interviews. Of the 370 trees that were planted in 2007, about a quarter died within the first year. Of the 325 trees still alive in 2008, 249 were still alive in 2012. This is a survivability rate of about 60%, using the SMUD definition of the term (trees still alive, regardless of condition).

Why did some trees die and some survive?

Some of it had to do with the water use classification of the species (as rated by WUCOLS), the time of year of planting (trees did better when planted during the local rainy season, October through April), or ultimate tree size (those with smaller mature sizes survived better than those with large mature sizes). But the only variable affecting tree survivability that made a statistically significant difference was homeowner stability. Tree survivorship after 5 years was 15% higher on owner-occupied properties that saw no change in ownership during the 5-year study period (aka “stable properties”). For each year after planting, tree mortality rate was nearly twice as high on unstable properties.

Maintenance practices were also much better on stable properties. Field researchers looked at correct planting location, support staking, irrigation, and mulch and trunk wounds caused by weed whackers. Using STF instructions to customers as standards, tree maintenance was rated one year after planting as either “good,” “adequate” or “poor.” Of the trees with “good” maintenance, 94% of them were found on stable properties and only 6% on unstable properties. Note that the maintenance rating is not the same as a tree condition rating. Tree condition was collected in 2008, but the findings were not reported in the 2014 paper. We can only infer that customers with good maintenance practices are more likely to have healthy trees.

Friends of the Urban Forest (San Francisco, CA)

Friends of the Urban Forest is a non-profit in San Francisco that plants street trees and provides some young tree care. The adjacent property owner is ultimately responsible for all maintenance including watering during the establishment period. The FUF Tree Care program visits FUF trees at 18 months, 3 years, and 5 years after planting. FUF tree care activities include structural training, stake and tie adjustment, making recommendations for future care, and collecting survey data on tree health. Trees are rated on a 1 to 5 scale with 1 = Very healthy, 2 = Good, 3 = Struggling, 4 = Almost Dead, 5 = Dead or Gone. Survey data is collected mostly by trained volunteers with oversight from FUF Certified Arborists.

Unlike the Sacramento program, trees are not free. Property owners must sign a maintenance agreement and pay a subsidized co-payment to get a FUF tree. Trees are not dropped off for owners to plant, as they are in Sacramento. Most FUF trees are planted in community workdays by volunteers, including the owners themselves, overseen by FUF’s Certified Arborists. No trees can be planted for renters or property managers without property owner agreement.

FUF trees are planted in the public right-of-way, which belongs to the City but must be maintained by the property owner. Owners are also responsible for keeping large trees pruned according to ordinance, and repairing concrete lifted by tree roots. A complex and expensive permit process is required to remove a street tree, so planting one is a significant commitment. By contrast, many STF trees are planted on private property and may be removed by the owner at any time.

FUF trees come in 15-gallon containers or, sometimes, 24-inch boxes, which are harder to establish than the smaller size trees given out in Sacramento. Generally the first 3 to 5 years after planting is considered the establishment period depending on species, wind exposure, and soil type.

San Francisco has a lot of rental property, and often renters are responsible for watering the tree during the initial three year establishment period. FUF keeps records of owner addresses and the contact information for any onsite caretakers if the owner is absent. For the three-year-old trees in this study, a little over 2/3 of them are considered to be maintained by someone other than the owner. “Non-owner-maintained trees” are indicated when the owner’s address is different from the tree planting address in the FUF database.

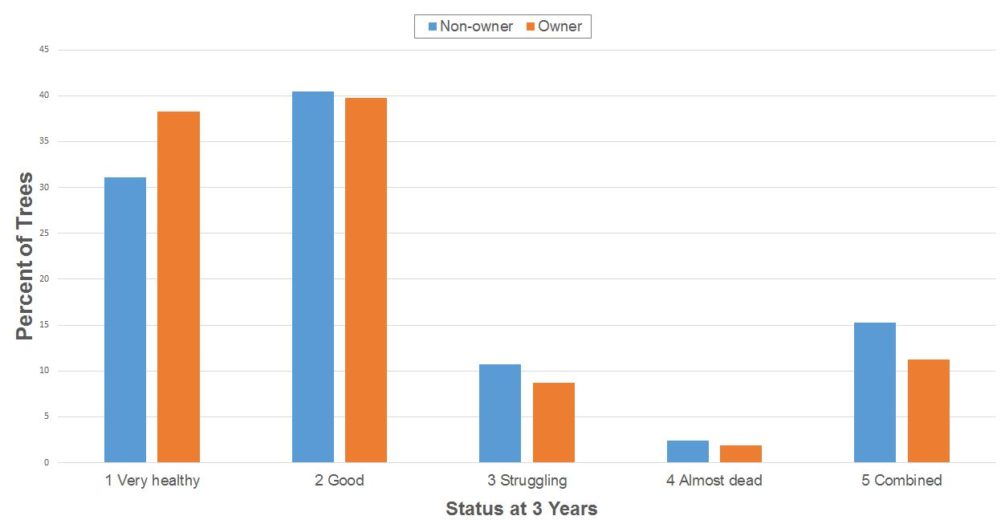

Owner vs. Non-Owner Survivability rates

Chart showing survey data collected on 4,454 three-year-old trees planted between 2007 and 2012. Data courtesy of Friends of the Urban Forest.

Friends of the Urban Forest generously collated and shared this data looking at nearly 4500 three-year-old trees, planted throughout the city of San Francisco between 2007 and 2012. At the 3-year mark, 87% percent of the trees are still alive. 15% are dead or missing. (Dead and missing trees are combined in the above chart).

While owner-maintained trees have a slight advantage, non-owner-maintained trees do surprisingly well. Overall, there is 85% survivability for non-owner-maintained trees and 90% for owner-maintained trees. By comparison, for 3-year-old trees in the Sacramento study, we find just under 80% survivability on stable properties and about 65% on unstable properties.

Looking at tree condition, owners and non-owners do very similarly, as noted in the table below:

| Maintenance | 1 Very Healthy | 2 Good | 3 Struggling | 4 Almost Dead | 5 Dead or Gone | Sample Size |

| Owner | 38% | 40% | 9% | 2% | 11% | 2777 |

| Non-owner | 31% | 40% | 11% | 2% | 15% | 1677 |

*Percentages have been rounded up to the nearest whole number.

Why are non-owner maintained trees doing better in San Francisco than Sacramento? A few possible explanations come to mind:

- The FUF program requires property owners to buy in by paying a (subsidized) fee, signing a maintenance agreement, and attending a community meeting. Owners then usually help plant their trees and those of their neighbors.

- The FUF program provides a great deal of advice and support before, during, and after planting.

- San Francisco is a city with rent control ordinances, resulting in tenants who live in the same place longer and become more invested in their surroundings and their community. This creates “stable” properties even when the occupants don’t own their residences. Sacramento does not have rent control.

Conclusion

While the Sacramento and San Francisco studies differ in several respects, a few common themes emerge:

- Good care during the establishment period, generally the first 3 to 5 years after planting, is vital for urban tree survival.

- Trees do better when they have stable stewardship during the establishment period, whether provided by a long-term property owner, property manager, or tenant.

- When property owners are required to be more involved in tree planting, we tend to see higher survival rates.

- Support provided by a community forestry organization before, during, and after planting can lead to healthier trees and better survivability.

In a world of starter homes and house flipping, stable properties may be headed the way of the dodo. How, then, can stable tree care be achieved?

New property owners might care for existing young trees if such care were specified in the disclosures during a sale. Given property sale data, community forestry agencies could also reach out to new property owners about their responsibilities – especially where tree care is required by local ordinance. When conditions are right to support long-term tenancies, such tenants can provide the stable stewardship for young trees, but diligent property owners are needed to pay the higher costs of maintaining mature trees. In short, a healthy urban forest needs all of us, so we can all reap the benefits.

Ellyn Shea is an arborist and consultant in San Francisco. Thanks to Allegra Mautner and Blake Watkins of Friends of the Urban Forest for compiling and sharing their data.

For other tips on how to prepare your trees for summer, you check out this article.

Interesting…seems we’ve known this for quite some time, but we’re not “promoting” it.