It seems like everyone wants green, tree-lined city streets. Under the filtered light of a towering tree canopy the air is cooler, the city seems more humane, and our minds become calmer. This idyll is far from reality, though, for many of us who walk along streets where trees are stunted or absent altogether. Street by street, these urban design annoyances become huge missed opportunities when looked at on a city-wide scale.

Streets occupy between one-quarter and one-third of a city’s total land area. If we can find ways to add well-designed green spaces and appropriate street trees to these publicly-owned lands, our rights-of-way have the potential to become verdant spines for our garden cities. So why aren’t we realizing this potential for significant urban greening?

One reason is speed. As a result of our desire for faster travel to more distant places, we have made an unwitting trade-off, sacrificing greener communities for speedier commutes. To understand how these tradeoffs came to be, it’s important to understand the thinking of traffic engineers, who we entrust with making our streets safe, and to explore what opportunities slower speed streets can yield for urban greening.

Learning to Speak Like a Traffic Engineer

Before we consider how speed affects the space available for planting, let’s look at a few key concepts from the world of traffic engineering including design speed, field of vision, and risk mitigation.

- Design speed. Design speed is the speed that a street is designed to have people travel along it. This foundational parameter affects the radius of corners along the street, length of stopping distances, existence of parking, lane widths, and stopping distances. Design speed is the reason that highways have big, broad turns that offer longer sightlines and greater stopping distances while slower speed streets are designed with tighter turns and more parking.

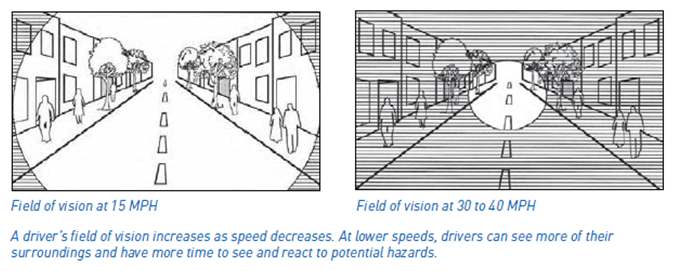

- Field of vision: Though the autonomous vehicle revolution appears to be coming, roads are still designed for human drivers. To the chagrin of some, this means that traffic engineers must ultimately contend with the evolutionary limits of our internal hardware: the human brain.Speed is not a natural condition for humans, so our senses begin to react in interesting ways once we begin travelling over a certain speed. One way it adapts to this increased speed is by limiting our field of vision as illustrated below. When travelling at a slower speed, it’s possible to observe a wider field of vision. When travelling on a faster speed street, vision narrows and obscures elements that are close while keeping elements that are a farther distance away in focus.Why does this matter? Well, imagine if an unexpected event arises — a ball rolls into the road or a pet wriggles free of its owner’s leash. It’s more difficult for a driver to see and react to these hazards if they are moving quickly. Knowing this quirk of human physiology, traffic engineers have traditionally sought to mitigate these risks.

- Risk mitigation: Recognizing the increased risk that comes with higher speeds, traffic engineers work to mitigate risks in a variety of ways. If a particular street calls for faster speeds, designers respond by creating more space at the edges of the road to push a potential “threat” further from the travel lanes, thus giving the driver more time to react. This creates the large shoulders and big swaths of soft grass at the edge of roads that are common on highways. Near cities, tall shrubs or conifers may block the view of a park and are sacrificed in the name of safety to improve sightlines.These ideas create a perverse cycle. When engineers notice a potentially dangerous situation, they often mitigate risk by removing obstacles along the side of the road. Unfortunately, this treatment sends the message to drivers that it is safe to travel at higher speeds than the street is designed for, rendering a potentially unsafe situation even worse, and making it harder to find space in the right-of-way for street trees.Fortunately, our street design standards are in the midst of a revolution. Recognizing that speed’s appetite for space is both exponential and insatiable, many communities are now looking in new directions to mitigate risk: reducing speeds to make streets safer. In doing so, they are discovering that slower speeds make communities more walkable, economically prosperous, and inviting for all citizens. As a result, more streets are designed to accommodate intended target speeds, creating new opportunities for urban greening in the right of way that did not exist just a decade ago.

Lowering Speeds for More Green

Let’s look at three ways that lowering speeds offers opportunities for more urban greening.

- Mixing Zones: One of the great benefits of slower speeds is that they make it safe to use streets for activities that are considered incompatible with higher speed streets. On a residential street, that might mean space where kids play basketball or an opportunity for urban greening. But these mixing zones can even happen on in-city streets. For example, at Bell Street Park in Seattle, a curbless street blurs the line between designated vehicular and pedestrian space. There is no straight line of sight and the street appears to meander. In part, this is achieved by incorporating maple trees and shore pines into the streetscape. At Winslow Way on Bainbridge Island, trees are planted in angled parking spaces both to visually break up the parking and to help slow traffic.

Several US cities have been borrowing from long-established Northern European countries that have been taking this mixing zone concept even further to develop streets called “woonerfs,” or living streets, where plants, cars, kids, and families all co-exist in an idyllic small space that would only be possible at slow speeds.

- Lane widths: On a narrow city street, where there is a lot of stop-and-go traffic, lane widths sometimes decrease to as narrow as 9.5 feet. As speeds increase, lane widths increase to 12, 13, or 14-foot wide lanes. Since space designated for streets is usually fixed, this increase in lane width often means that plants and trees are squeezed out completely or are given less room (and soil) than is optimal for long-term plant health and viability.Thankfully, cities are pushing back. New guidelines are being incorporated into national and local standards that shrink lane widths to a more appropriate scale and either encourage or require street tree planting.

- Intersections: Because at least two directions of travel are crossing one another, intersections are natural conflict points, the place where most collisions occur, and the most dangerous part of any street. Traditional roadway engineering, which focuses on moving traffic quickly, partially mitigates inherent risk by mandating large “sight triangles:” zones of no visual obstruction at intersections. This is why, for example, a row of street trees might end a good distance from an intersection. By removing trees from our cities, though, we’re also removing one of the street elements that helped control vehicle speeds.For slower speed streets, plantings and street trees can help reinforce the street’s target speed by adding a sense of enclosure, creating psychological friction, and promoting a finely-textured aesthetic best enjoyed at slower speeds. In the High Point neighborhood of West Seattle, slow speed, and conversations with permitting agencies allowed for small planting pockets at intersections. Though the plants are never taller than 30” to preserve lines of sight to oncoming traffic, their presence both helps make the neighborhood a welcoming place to walk and reinforces the need to control speeds.Another example of how slow speeds allow for planting at intersections is small traffic circles that can be converted into traffic gardens containing trees or other plantings. Because drivers must circumnavigate them, these traffic gardens minimize the potential for collisions. Some of my favorite examples in my neighborhood are overflowing with seasonal bulbs and well-tended perennials as neighbors, some who live in apartments without space for gardens, have adopted these spaces as their own.

As the slow speed revolution continues to expand across the American landscape, opportunities for more, and better, planting in our rights of way will continue to grow. For those of us who advocate for more urban greening, let’s also advocate for calmer, slower streets. By doing so, we’ll make streets safer and plant the seeds of change for greener communities.

Figure 1: Bell Street Park, Hustace Photography

Figure 2 Some of Winslow Way’s street trees, located between angled parking stalls.

Figure : Plantings of low-growing shrubs along the curb at an intersection in the High Point neighborhood in West Seattle.

Leave Your Comment