Earlier this year, I wrote about a study by Dr. Jessica Sanders, Director of Technical Services and Research at Casey Trees, that concluded that “apparent available soil” was a good predictor of ultimate tree size. Now, Dr. Sanders and two co-authors, Jason Grabosky and Paul Cowie, have published a complete version of their study in the March issue of Arboriculture & Urban Forestry.

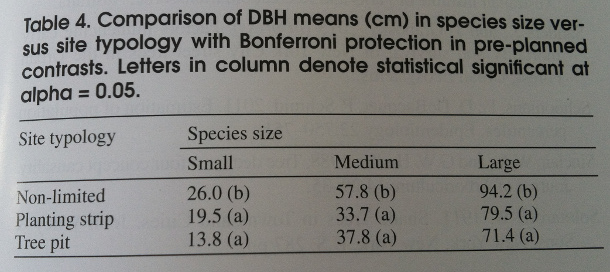

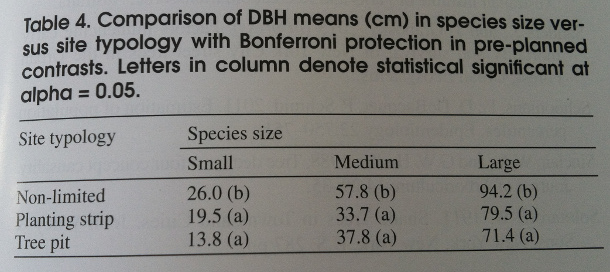

The study looked at trees growing in three types of landscape types: tree pits, planting strips, and unlimited soil and discovered, among many other things, that there was a significant different in maximum sizes between planting site types. In their words, “Regardless of the size class of the tree, the data showed reduced planting space resulted in reduced maximum size.”

The chart above illustrates this perfectly. As you can see, regardless of species size, trees flourished in larger soil volumes, in some cases nearly doubling their diameter at breast height (DBH), a metric that is assumed to be a viable surrogate for age, and closely associated with canopy size.

Sanders, Grabosky, and Cowie note in their discussion that there is no accepted definition of a useful end point to the service life of an urban tree, and also no established definition for “normal rates of attrition and life expectancies for trees in urban settings.” In some respects, it has been convenient to avoid determining these expectations – it allows us to avoid evaluating some of our attempts to improve the urban canopy as rigorously as we should. The authors point out, rightly, that long-term expectations for tree performance are usually only implied. We primarily focus on establishment success, which is critical for long-term viability of urban trees, but hardly guarantees it. They go on to say that “the ability to predict plant performance and longevity with relation to design choices is crucial for an appropriate program analysis” (this comment was in reference to the Million Tree initiatives that are increasingly common in major cities, including in New York, L.A., Philadelphia, and others).

The authors make a great point, here. The conversation about urban trees is increasingly turning in to one about performance – everyone who loves trees, myself included, cite the many benefits provided by trees. But most of our trees aren’t big or healthy enough to deliver those benefits. By establishing a life expectancy for trees in urban settings, we can begin shifting the focus of our programs from simply planting trees to growing them. By following that approach, we can minimize premature tree losses and maximize the ecosystem services that are so dramatically increased as trees grow and mature.

Leave Your Comment