In the world of Low Impact Design (LID), the terms raingarden and bioretention are often used interchangeably. However, there are some inferred differences between these two LID practices. These differences were highlighted during recent work with the Washington Department of Ecology, which designated Silva Cell as functionally equivalent to a bioretention facility.

In my professional life, I have had the opportunity to work for two firms that push themselves to be innovative in their approach to integrating innovative stormwater management into beautiful design, InSite Design Studio and The Kestrel Design Group. During my work at InSite Design Studio, our team worked to complete dozens of raingarden designs for residential lots, which were funded by Washtenaw County, MI through grant funds. This raingarden program is still going strong and is spearheaded by my partner-in-crime from grad school, Susan Bryan (Great work, Susan, I miss you and all the great minds at InSite!).

While both raingardens and bioretention facilities are defined as a combination of soil and plant material used to capture and treat small stormwater events, bioretention facilities are held to a higher design standard. Bioretention facilities are specifically designed and engineered to meet project goals related to saturated hydraulic conductivity, pollutant removal, and healthy plant growth. They are also often inferred to be larger-scaled systems with designed outlets to control system hydraulics and media that is engineered for both healthy plant growth and stormwater holding/filtration capacity. To read more about the differences between the two terms, I recommend the Low Impact Development Technical Guidance Manual for Puget Sound (December 2012) and the Engineering Concepts for Bioretention Facilities: From Rain Gardens to Basins presentation from NJASLA (February 2011).

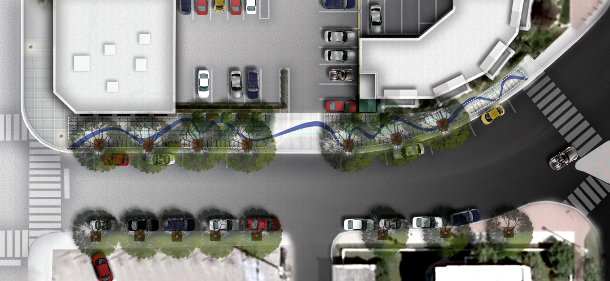

Recently, my co-worker, Marcy Bean, was the project manager for a bioretention design for the City of Calgary that used Silva Cells for healthy tree growth and stormwater management. By using just trees and soil, the 100-year storm event will be managed within the bioretention facility, thereby reducing flooding, pollution, and attendant damage downstream. We are excited to see this project go in the ground and happy we could help Calgary work toward its goal of a cleaner Bow River.

This schematic shows how trees and soil contained in a Silva Cell system will be used to manage a 100 year storm event in Calgary, AB.

Certainly, the terms raingarden and bioretention will continue to be used interchangeably at times, but we appreciate the nod to differentiating the two LID practices and recognize the importance of knowing the specifics of how stormwater is treated on both a project-level and a watershed-level. Keep an eye open for this differentiation and let us know how these terms are used in your neck of the woods.

Sarah Sutherland is a sustainable landscape architect with the Kestrel Design Group.

Great article. It is good to see that folks are making a distinction between the two. In Vermont we’re focusing more on the distinction between LID, green infrastructure, and green stormwater infrastructure. It’s a fun process that will hopefully benefit us as we push these concepts forward. Keep up the good work.