This is Part 3 in the History of Street Trees – British Isles series. You can read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

The lack of costly infrastructure as defensive walls, previously discussed at the beginning of part two of this series, allowed British cities to expand piecemeal into the countryside, with lower population densities. In a sense all British cities, whether English, Irish, Scottish, or Welsh, were suburban (aside from the city centers). Some of these cities distinguished themselves by later becoming “cities in a garden” or cities in a forest, particularly Edinburgh and Bath. The establishment of London’s underground rail transit system, “the tube,” was the first modern transit system in the world, and a direct result of this expansionist suburban development model of single-family housing.

Trees in the Countryside

The long legacy of gardening landscape and trees in the British Isles is no accident.

Major British cities, except Bath, had high density tenement centers. In Dublin it was “the liberties,” London had “the East End,” and Edinburgh had “the Closes.” But high density housing was not an ideal in Britain or perhaps as accepted as it was on the European continent. The detached country-house for the squire/lord/earl was the aspirational model: the villa with its own four walls and very large back gardens. In other words, a single-family home on its own lot, with an elaborate gardenWhen the British aristocracy and later the merchant class saw the value of trees, they saw them as reserved for special people, not the lower classes. The British speculative development model took advantage of that by embedding private fenced and gated parks into the process of building new housing. This financial model came complete with a dedicated revenue stream for upkeep, which levied fees for the long-term maintenance of these squares, crescents and circuses from the surrounding residents.

When is a tree more than a tree?

British paintings say a lot about the role of trees in British society, and they are most famous for their landscapes. Looking closely in the foreground, there are trees – not buildings, not people. Large majestic trees punctuate pastoral or pictorial landscape scenes, and occasionally there are inconsequential tiny human figures moving about. In these paintings trees are in the foreground and they were painted with great care.

British Landscape Painting by Gainsborough; note scale of people and trees; realistic detail in trees (Image: Telegraph.co.uk)

Unlike most non-British landscape paintings, these trees are painted so accurately, I can tell the species. These tree portraits honored the trees, conferring character upon them. These trees were meant to convey important messages to the viewers, particularly about the owners of these painted British landscapes: longevity, permanence, peace, wisdom, and wealth. These were the kinds of privileges conferred by God upon Kings, and by extension the aristocratic families who owned the lands being painted, granted to them by the King. There are so many beautiful British paintings of large trees. Take a look sometime, with the thought in mind of a tree as a visual message of pre-ordained power and land ownership. Though at first glance they may only appear to be oil paintings of landscapes, it’s the tree that marks time and confers status and displays continuity.

Green Space in Cities: British Style – “Rus in Urbe”

As in other spheres, London was the taste-maker for the placement of trees in the city for all of the British Isles. There were other major cities in the British Isles besides London, but London’s political and financial domination was so great that all roads led back to it. London’s major method of colonial control of Cardiff, Edinburgh, and Dublin was to allow these three satellite capitals intermittent independence. These periods of semi-independence allowed the capital cities to flourish because of the wealth of the attendant aristocrats and civil servants that moved in. These sudden and large influxes of cash meant new buildings, new streets, new high end houses, new squares – and new urban trees. However, if there were any discussions of independence, the London aristocracy withdrew that power and wealth back to the Houses of Parliament. This taxation without representation model created a kerfuffle in the American Colonies when they declared independence from England in 1776.

Despite London’s outsized influence, other cities still evolved in significant ways. The resort town of Bath, for example – a town famous for rich and titled barons –influenced the development of parks and squares in the housing developments which paid for these treed green spaces. What’s perhaps most remarkable about green spaces in urban areas in Britain is the similarity of evolution in the four capital cities. The first green spaces in all of the major cities except Dublin started out as Atriums in Roman houses (invaded 55 BC by Julius Caesar), which later influenced Monastic herbal gardens. Similarly, quadrangles in universities is in turn an outgrowth of the green spaces surrounded by cloisters that dominated the layout of medieval monasteries.

After the quadrangles of Oxford, Cambridge, Trinity, and Saint Andrews universities came squares. The square became a model for development anchored by a green space in London, and in its capital cities of Dublin, Edinburgh, and Cardiff.

In downtown Dublin, 1592 Trinity College occupies pride of place, immediately south of the Liffey’s main crossing – O’Connell Bridge. Inside a tall iron fence, imposing stone Georgian buildings give no hint of the green oasis on the other side of the buildings. Inside the college walls are numerous quadrangles, perfectly green lawns dotted with the occasional, centuries old, stately tree.

A panorama taken from Parliament Square. The row of buildings is framed by the Public Theatre on the left and the Chapel on the right. In the middle lies Regent House with its archway leading to the Front Gate (Image from Wikipedia)

University of Oxford’s Exeter College Quadrangle: became the model for London Squares (Image: Conference-Oxford.com)

Cambridge and Oxford used this same green quadrangle or quad device, and had done so since the 1200s. Cambridge, Oxford, Trinity, and St. Andrews were the universities where the young British men of means (aristocrats) were educated. These were the same individuals who went on to develop Britain’s first residential quads, or squares, in London: Covent Gardens in 1630, London’s lawyers apartments at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in the 1650s, and in 1660, Britain’s first named Square: Bloomsbury Square.

The first of London’s built squares, Covent Garden, lost its central green space to the temporary and eventually permanent market stalls, along with a bumper crop of pickpockets. (All squares from that point forward had fences to keep out the riff-raff, get-away horses, and heavy horse-drawn carriages). Four of London’s next five squares were built prior to 1700: Leicester Fields, Golden Square, Red Lion Square, and Kings (Soho) Square. All had pathways, green turf grass panels surrounded by now the obligatory exclusionary fences and, at last trees! Almost 350 years later all of these London squares remain, some with 200+ year old trees.

Here we see large old trees in the city, growing in un-compacted soils that were formerly pastures. Their recipe for urban tree success was large un-compacted soil volumes! That wasn’t so hard – was it?

Another new model green space showed up on the scene in the form of Royal Parks that were previously used for hunting. The Royal hunting parks in London included Regent Park, Hyde Park, Green Park, and St. James Park. In Dublin it was Phoenix Park, now the largest urban park in Europe. Ironically enough these Royal Parks became the public open space for all – a place for the proletariat.

Even though trees were recognized as an economically important and a beneficial factor in European cities as early as 1500 in Holland and Italy, the British were very late to the game of trees in public places, such as streets and canals. Their model for trees in the city was speculative, private fenced squares (mini-parks or pocket parks or in modern parlance: parklets) surrounded by luxury row-houses. As late as 1780 in London, trees were considered a liability in cities. Several screeds in newspapers were written to this effect. However by 1800, trees had been elevated dramatically and were considered as necessary as buildings in the city.

At first, street trees were only planted on the grand processional streets of the main cities: Pall Mall in London, O’Connell Street in Dublin, and Prince Street in Edinburgh. Street trees purposefully began to be used to link these open spaces of parks and squares. For the row houses that did not have a front door view on squares, street trees were a way of spreading the wealth, so to speak. A row house resident might not be able to afford the house on a square, but at least they lived in a nice enough neighborhood that had street trees.

In sum, Roman atriums led to monastic cloisters which led to university quadrangles and moved into the city in the form of private squares and Royal Parks converted to public parks. The final piece that stitched all of these green spaces together into a coherent whole were the street tree plantings beginning in the 1750s and continuing on until today. The idea of the leafy London Lane and the idyllic city townhome was brought to us by street trees.

Princess Street: English square taken to a new level beyond London’s squares; considered one of the most beautiful treed streets in the world (Image: Destructor.de)

In Dublin’s Fair City…

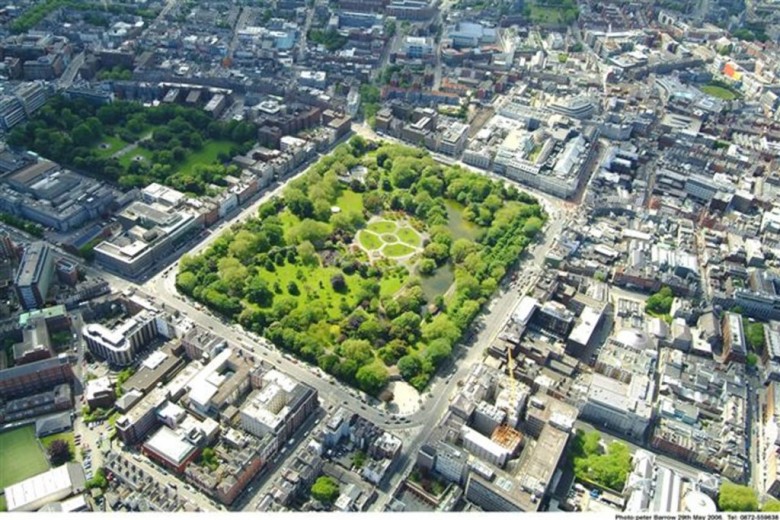

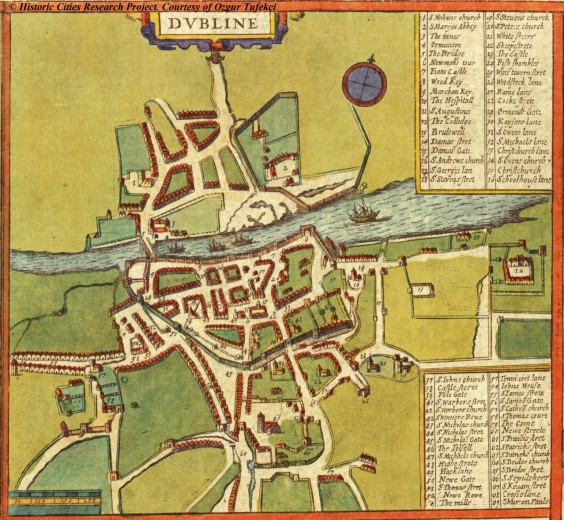

Dublin had a very brief golden age from about 1750 to 1800; in that time a number of privately developed squares and high-quality row house developments were built such as St. Stephen’s Green, Merrion Square, and Fitzwilliam Square. Also built during this boom were the Customs House, the House of Parliament, an updated Trinity College (originally founded in 1592), and a modest canal system. Unlike the Dutch , Irish and English canals rarely had trees planted on their banks. In Holland’s flat landscape, constant wind powered their barges with sails. In British and Irish Canals, horses pulled barges along a tow path where trees could otherwise have been planted. All of Dublin’s building growth came to an abrupt halt in 1800, when Ireland’s “Home Rule” was dissolved and Irish representation was returned to Westminster’s Houses of Parliament without Irish people. A number of failed revolutions, and the Irish Potato famine of the late 1840s, depopulated Ireland by the millions and sapped its wealth so that from 1800 to 1970 Dublin was very much a provincial city and a financial backwater city of the British Empire. As late as the 1970s it was possible to walk through entire sections of Dublin which had had no new buildings for over 150 years. As one would guess, street trees were not on their infrastructure list.

There was a small boom in housing construction after the World War II in Ireland. This was made up primarily of row-houses without any squares, and modernist high-rises surrounded by large expanses of lawn. Without exception these were green-field developments. These buildings were also built with modern earth moving equipment, so compaction was everywhere. Based on this constraint, it is probable that no trees would have survived. Most of these houses were for rent or lease, some allowed ownership, but very large percentages were for the working poor who had never lived in a city house. These row-houses, flats, and tower blocks had not been designed for aesthetics, and there were no street trees or any other public trees. They were unnecessarily bleak places. London and Edinburgh were cursed with this same housing idea. Not very surprisingly, this housing stock was massively devalued in the 2000’s and is unlikely to rebound for perhaps a generation.

Brighton Square: Portrait of the Value of Trees in Square Gardens as a Young Man!

The post World War II housing boom tree-less developments are a stark contrast to Brighton Square.

While attending the Irish Botanic Gardens I was hired for the renovation of a small private triangle of land called Brighton Square in Dublin. This residential Square was built on a green field on Dublin’s southern outskirts, in the late 1850s. This was long after private squares were no longer the fashion in London. Even today, Brighton Square is a keyed entry for residents only; one of the few remaining private squares in Dublin. James Joyce of ‘Ulysses’ fame grew up there, unfortunately for me, none of his genius rubbed off.

Part of the Brighton Square improvement project, was clearing, and pruning large perimeter trees to open up park views, from outside: to see the tennis courts and central lawn; from inside: to see the Victorian brick row-houses. Pre-earthmoving equipment, Brighton Square (like its London, Edinburgh and Bath compatriots) had been hand-built. The black soil was high quality former pastureland, rich, un-compacted loam. In these oxygen rich soils, trees grew very large, and readily. No new tree-planting was necessary for the square’s rehabilitation. Except for its triangular shape, Brighton Square was a very typical square of the type, a green peaceful oasis in a sea of brick, concrete and asphalt, a private keyed, retreat for about 70 families. The brick row-houses with slate roofs, then as now, were very nice but not spectacular, again typical for the type. This development model, around these large trees and green space is still economically relevant now, 150 years later. Unlike modern estate developments which in huge numbers are bankrupt, these row-houses, today, sell for more than €1 million each, even after 2008, when Ireland’s 15 year real estate bubble burst: a powerful example of large trees that increase and maintain real estate values.

St Stephen’s Green: pre-eminent square in Dublin; also highest priced real estate in Dublin (Image: walkinmyshoes.ie)

Historical image of St Stephen’s Green; note prominence of trees inside the square extending to land adjacent the square (Image: Wikipedia)

I grew up a Catholic boy in Ireland, in a 1700’s thatched country house with walled gardens and an unusual tree collection, especially evergreens: Brazilian Monkey Puzzle (Aracauria araucana), Irish Yew (Taxus baccata) trained into arch covered walkways, Mediterranean Holm Oak (Quercus ilex), and other exotics. I already described the powerful influence of the huge cloister of Irish Yews (Taxus baccata) at the monastery where I went to middle school and high school. I began my horticultural education at Ireland’s Botanic Gardens in Dublin. When Ireland became independent in 1922, these Botanic Gardens were nationalized and became public gardens. However, for about 100 years, these were essentially private gardens for the well-to-do ”gentlemen of taste,” Royal Dublin Society members, and was the case for all Botanic Gardens in Britain until the founding of Derby Botanical Gardens in 1830.

When I completed my education at the National Botanic Gardens of Ireland in Dublin in 1980, I assumed that my professional future was bleak and that by extension, so was Dublin’s and Ireland’s. Half the Republic of Ireland’s population was under 25, and unemployment was over 20%. Looking back on this time I liked to say that Ireland’s economic recession would soon be 800 years old. For me, an Irish recession of 900 or 1000 years seemed entirely possible. Ireland was very much a second world country, almost exclusively an agricultural economy, with significant poverty and a net population loss from immigration for over 120 years. After short professional stints in Germany and Norway, I left Ireland and Dublin in the early 1980s for the United States to pursue a professional degree in landscape architecture at the University of Minnesota. I’ve been here ever since, but the history of street trees of the British Isles remains a topic very dear to me.

L. Peter MacDonagh is the Director of Science + Design at The Kestrel Design Group.

References

Haito of Reichenau; 816-836; Plan for Saint Gall.

Horn W., E. Born; 1980; The Plan of St. Gall; University of California Press.

Jones S., R. Martin, D. Pilbeam; 1994; “The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution”; ISBN 0-521-32370-3.

Lanfranc; 1165; Plan of the Abbey at Canterbury.

Price L., 1982; The Plan of St. Gall in Brief: and overview of the three volume work by Walter Horn and Ernest Born; University of California Press.

University of Edinburgh 1583

Angel, L.J., 1984, “Health as a crucial factor in the changes from hunting to developed farming in the eastern Mediterranean”

Caspari R. & L., Sang-Hee; 2007; “Older age becomes common late in human evolution”; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101 (20): 10895-10900.

Haito of Reichenau; 816-836; Plan for Saint Gall.

Top image Christ Church College Quad Flickr credit: Elentari86

Leave Your Comment