This is Part 2 in the History of Street Trees in Britain and Ireland. Read Part 1 of this series here.

The cultural, religious, medical and agricultural vacuum that followed the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire led directly to the establishment of independent, self-sufficient catholic monasteries. The dominant monastic culture came directly from Britain, specifically Columban Ireland: wandering monks became missionaries and gained followers wherever they went. Over the next several hundred years, monasteries religiously re-defined and enlarged the old boundaries of the Western Holy Roman empire. Using papal authority and religious piety they became the centers of peace and culture in Europe. Un-walled and undefended because of their religious shield many of them, particularly in Britain (with 500 monasteries), housed thousands of individuals and persisted for almost a thousand years, until 1538 when Henry VIII ordered the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The first western European monasteries, not surprisingly, started in Ireland with native Celtic Irish.

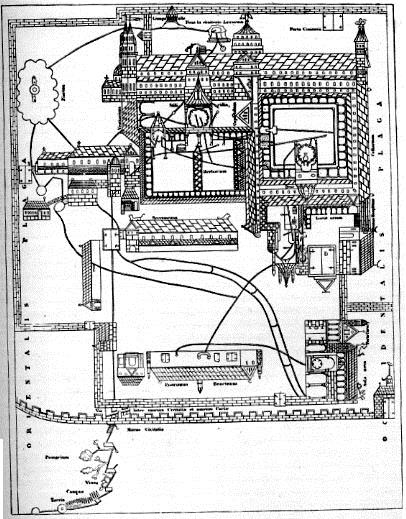

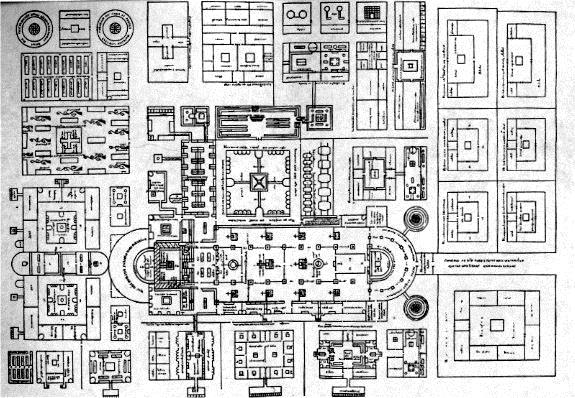

In addition to the famous monastic scriptoriums, vineyards, and fermenting of wine and brewing of beer, this era brought the less well known Cloister Gardens. At first they were believed to be a simple square grass panel location with a fountain; over time they evolved into fully fledged gardens. The plan of St. Gall Monastery (816-836 AD) is an idealized view of the buildings and gardens of a monastery. The plan shows separate spaces for the following gardens: medical herb, vegetable, orchard, and two separate Cloisters. A later (1165) plan of another monastery in England, St. Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury, also shows gardens, vineyards, orchards, and an irrigation system.

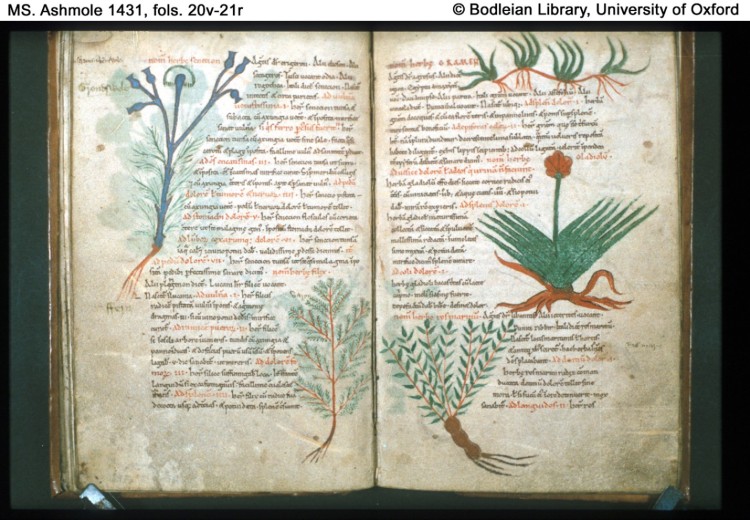

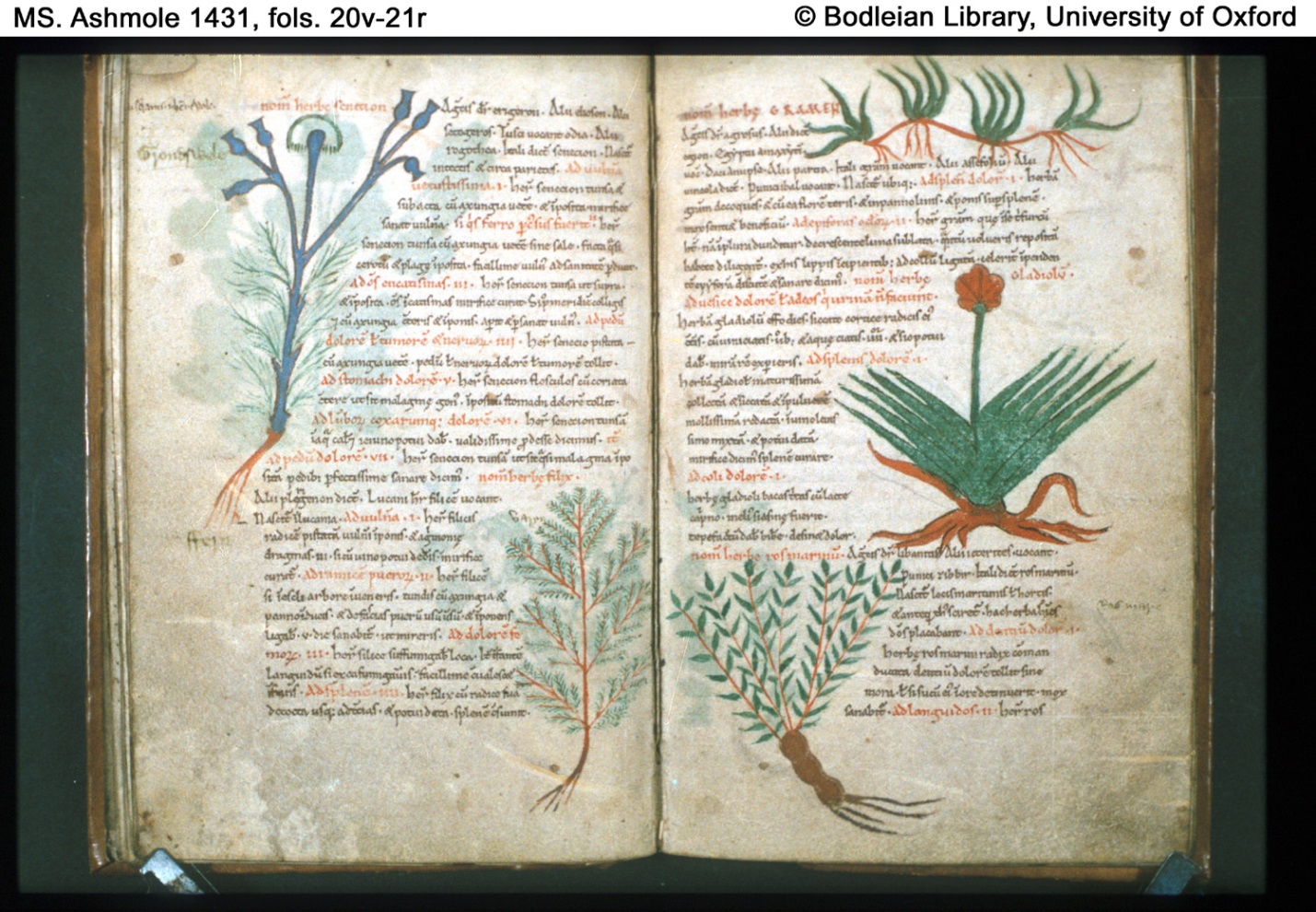

Excerpt from a book of plant drawings from St. Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury (Image from blog.metmuseum.org)

Physic gardens (700AD), which were gardens of medicinal or healing herb, were placed in squares surrounded by monastic cloisters. Later, these gardens added culinary herbs and orchards of unusual fruits and nuts trees.

Plan of the cloisters at Canterbury which dates from the year 1165; fruit-gardens and vineyards are shown outside the walls (Image from gardenvisit.com)

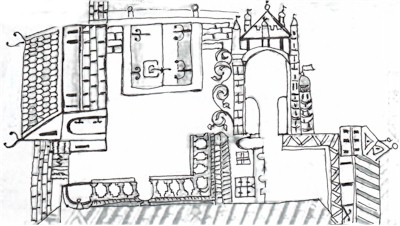

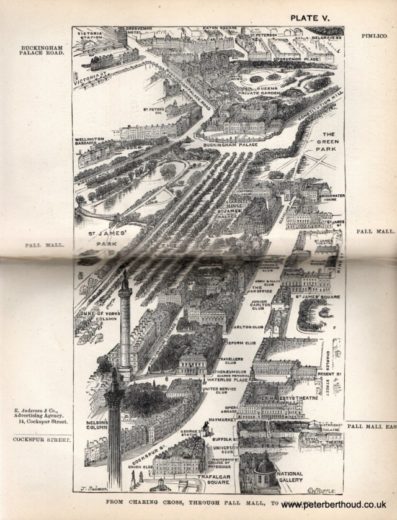

Combination of a bird’s eye view with perspective showing the gardens at Canterbury (Image from wyrtig.com)

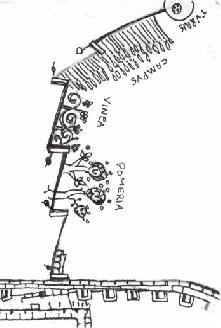

Close-up of the orchards and vineyard at the gardens at Canterbury (Image from wyrtig.com)

Cloistered Upbringing

The monastic stone cloisters that came back to Ireland with Italian Franciscans were re-interpreted in a rather unique way: the walls and roof of the cloisters were no longer stone and brick, but instead living tree branches. I see this as another Celtic variation on theme of “the wood and the trees are not separate.” Cloisters made of living trees remove the human from between god and spirit, and places humans under trees inside the essential sacred. This is likely inspired from the Celts or Saint Francis, the Christian naturist.

Ireland’s Gormanston Castle – now a school run by the Franciscans. The castle is where the Franciscan Brothers lived. I went to school in the mid-century modern building next door. The tree in the foreground is a Horsechestnut, the large round Irish Yew (looks like a giant pincushion), also has an entry & is a cloister inside. (Image from britainirelandcastles.com)

Cloister in living trees at Franciscan College in

Gormanston, Ireland (Image from www.dave-cushman.net )

Trained yews at Franciscan College in

Gormanston (Image from http://www.studyco.com/article/11075-Meath)

The legacy of these cloister gardens is still seen in Gormanston, Ireland, where the boarding school I attended is located. Run by Franciscan monks, the school included a castle from the late 1800’s that the brothers lived in, right next to the mid-century modern classrooms and dormitory building where the students lived and studied. In front of the castle there was a huge cloister of Irish Yews (Taxus baccata) that had been formed by bending and tying branches to make arches and galleries for people to stroll in. Each one of these archways was about 15 feet wide. Irish Yews at four corners were trained to arch into the center, towards each other, to create a living roof with four arches about 8 feet tall. The trained branches grew up about another 40 feet above the cloister area. This is where a person walked. We had a set of four arches at my house; at my school there were at least 30 arches, maybe as many as 40 arches. Even for a teenage boy with lots of things on his mind, always trying to be cool, even indifferent, this cloister of living trees was awe inspiring and these were perhaps the most memorable trees I’ve ever walked under.

With a sea like that, who needs walls?

When the Norman William the Conquerer defeated Harold the Saxon in 1066 in Hastings, England, both islands (Hibernae and Britainia) containing at least four individual countries soon became essentially one country – Britain, under a single ruler. There were lots of changes, but there was no complete displacement of peoples. The rise of Henry VII (Father of Henry VIII) of the House of Tudor (see BBC’s “The Red Queen, The White Queen and The Kingmaker’s Daughter” for more about this era) essentially re-unified all the countries of these two islands into a single nation of Britain (Scotland, Wales, Ireland), which essentially remained that way until 1922. This was most unlike continental Europe which, except for France, became a cluster of hundreds of city states constantly warring amongst each other. Without exception, in continental Europe any city of any size (10,000-20,000) had to spend, build, and maintain huge defensive walls.

These same city-state defensive pressures were much less evident in British cities. Why? The English Channel and the Irish Sea were the most impregnable moats. These moats are both over 20 miles wide. Only the oldest cities in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland had walls, and most had only partial or minor walls, or perhaps only wooden palisades or fences. Certainly, the huge expensive star forts of Europe with their massive hand-built earthworks were very rarely built in Britain during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. This meant that trees planted on city walls in Europe for strolling (like those in Paris) were not planted on those walls. The absence of walls allowed a new kind of development- suburban sprawl.

Those Troublesome Tudors and Trees

In 1536 Henry VIII enacted the “Dissolution of the Monasteries,” over 850 of them, displacing 10,000 monks, nuns, etc. It was a land grab, and Henry VIII came into over 20,000 square miles (a parcel of land the size of West Virginia)/15 million acres/ over 25% of all the arable farmland in Britain, most of which he sold to favorite Knights and Ministers of his Court. Suddenly, Henry had cash and the UK had hundreds of new landowners with vast estates. These are the English aristocrats of today: Earls, Lords, Ladies, Duchesses, Marquis, etc. With all this land, these newly minted Lords and Ladies, in addition to collecting rents, had a place to gather out-of-doors. Typically, the new castles and palaces were built using materials from the newly vacant monasteries. The remains of the monks’ cloister gardens, their interesting geometric layout, herbs, medicinal plants, orchards, topiary hedges, and allées of pollarded trees (which provided yearly trimmings for firewood) now belonged to the new landed classes and could be used for recreation. Being out-of-doors was now fashionable.

Pall Mall was the activity of leisure for the recently landed aristocrats. When in London at the monarch’s court or the Houses of Parliament, Pall Mall was played by the royals and the recently rich elite, including Mary Queen of Scots, James I, and Charles I. Both James I and Charles I played Pall Mall under the tree lined allée of the Pall Mall adjacent to Buckingham Palace. The significance of this outdoor spor being fashionable is not to be underestimated in the shaping of outdoor space in Britain, even to this day.

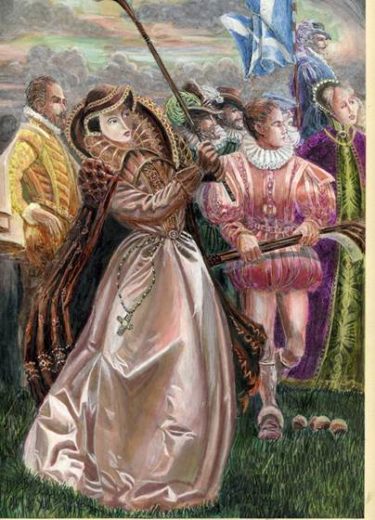

In 1567 Mary Queen of Scots, first cousin of Henry VIII, was seen playing Pall Mall on the grounds of Seton Palace in Scotland, less than 30 years after the end of the Monasteries.

Image of Mary Queen of Scots playing Pall Mall (Image from www.molespace.co.uk)

James I of England, successor of Elizabeth I, suggested in an open letter before his death in 1625 that his first son, Henry, practice the sport of Pall Mall. The next king of England, Charles I, is spotted playing the game in 1639. The tastemakers – royalty – were playing Pall Mall under allées of trees. Aristocrats imitated the royals and soon the Pall Mall lawns with precise tree spacing were showing up at the aristocrats’ new houses.

Pall Mall, which is essentially a boulevard beside Buckingham (a boulevard really), was laid out in its current position in 1661 by Charles II of England. His father, King Charles I, wanted to make this Pall Mall the best in Europe. This Pall Mall was famously lined with an allée of trees to provide shade and a picturesque setting for the promenading carriages to view. The current Pall Mall road leads directly to the front door of Buckingham palace, now lined with double rows of trees on each side. English Royals in processional carriages use this street on special occasions. The wedding of Prince William to Kate Middleton a few years ago including a procession along Pall Mall once again brought attention to this extraordinary boulevard, made significant to Britain by an outdoor game and street trees.

Very nice couple of posts – thanks.