Creating a Standard for a Green Infrastructure Sidewalk

This is the first of a series of five posts featuring case studies that illustrate the need for a paradigm shift for how streets and sidewalks are designed and constructed. This new paradigm for Green Infrastructure is based on Creativity, Collaboration, and Compromise (CC&C), and is demonstrated by the streetscape design of landscape architects Claude Cormier + Associates at 300 Front Street in Toronto, Ontario.

To turn a sidewalk into Green Infrastructure requires an integrated and coordinated effort, and the sidewalk at 300 Front Street reflects the substantial progress the City of Toronto has made in this approach. Lacking the support of City approved standard details and policies, a lot of CC&C from the landscape architect to City of Toronto staff to the general contractor was needed to make it possible. Any party could have objected that the proposed solution was “not an approved standard” and jeopardized the project, but thankfully no one did. As a result, the 300 Front Street project has provided invaluable lessons in the development of emerging standards and helped create true Green Infrastructure.

CC&C at 300 Front Street project:

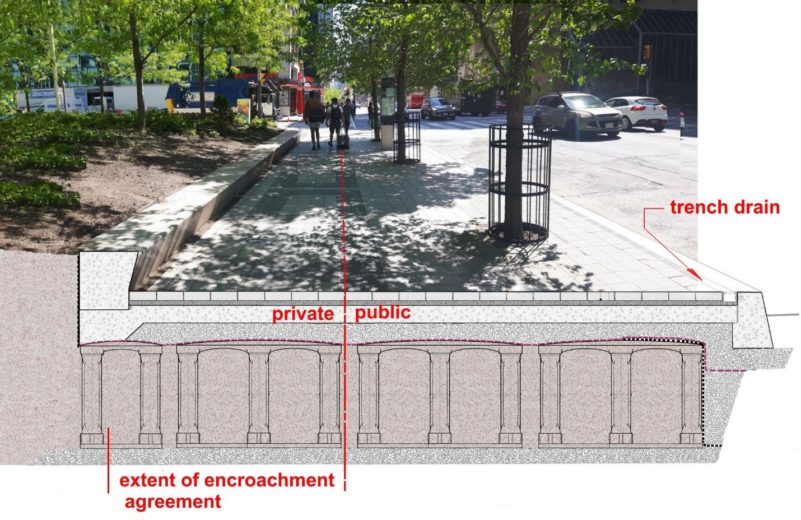

More Soil: Silva Cells give the trees access to soil beyond the sidewalk to the soil in the planting area on private property. The sharing of soil between the public right of way and private lands has been the cornerstone of the City of Toronto’s urban forest. This mostly occurs on the tree-lined streets of residential neighborhoods where trees planted in the public right of way can access soil in adjacent front yards. The 300 Front Street project mimics this and demonstrates that this is possible in high-density, urban development.

More Space: City planners secured an encroachment agreement with the landowner for the use of private property for increased room for pedestrians and more soil for the trees.

More Water: A passive irrigation system (a trench drain at the curb) collects rainwater from the sidewalk and directs it back to the newly planted trees, which provides aeration and the option to fertilize the tree using a compost tea.

Fig,1 The section illustrates the soil under the public sidewalk connected with the soil on private property using Silva Cells.

Urban Forestry vs. Urban Design

Fig.2

The designers of the 300 Front Street project, Claude Cormier + Associates, understand the need for larger tree openings and put a tremendous amount of effort into creating the ideal conditions for growing a mature, healthy tree. Despite this, some of the design decisions have issues. As Fig. 2 illustrates, the small tree opening is encroaching into the tree trunk and the critical zone of rapid taper, which can have long-term health consequences for the tree. Additionally, because clients often demand a larger tree and a more mature looking canopy, compromises are made in the selection of the trees. In this case, the root ball specified was larger than the planting area, forcing the tree to be planted before the unit pavers were installed. This resulted in the tree being planted during a very cold, well-below-freezing January. If the tree opening is larger, the “hardscape” work could have been completed, allowing the tree to be planted at a more optimal time, and ideally planted straight. Fig. 3 shows the tree planted too low, creating a bathtub effect, rather than above the level of the sidewalk to provide proper drainage. The designers of this project wanted larger tree pits, but found themselves in the middle of a struggle between urban foresters that want more space for trees and engineering departments that want more space for pedestrians. Too often the urban forestry team has to make the compromise, which often results in solutions that make no one happy, particularly the tree.

Fig.3 Planting trees to low in city sidewalks creates drainage problems.

For more details see Up By Roots by Jim Urban

Fig.4 300 Front St.

Had the paver installer started 1 inch to the left and 1 inch further in the other direction there would have been no need to cut any pavers around any of the trees pits.

Sony Centre, Toronto

This is costly to the tree’s health but also creates future, the unbudgeted cost to Urban Forestry Operations when these trees need to be replaced. Forestry Operations will have to remove and replace the unit pavers and steel plates, which is beyond the typical scope and budget of their work.

The unit paver work was also more difficult because of a lack of coordination. The general contractor did not communicate to the unit paver installer that the tree pits and metal frames had been precisely located, precluding paver cuts at any tree pit. This resulted in the installer starting at one end of the field of pavers and working to the other end, and every unit paver around every tree pit having to be cut.

In contrast, at the Sony Centre (now known as Meridian Hall) project in Toronto, (Fig. 4) with a similar design, clear instructions were given to the unit paver installer. Not a single unit paver had to be cut for the entire project.

For the City of Toronto, the new generation of tree planting details and specifications address many of these issues. They will form the basis for a complete set of drawings and specifications that will provide site supervisors what they need to ensure that such coordination miscues do not happen.

Landscape Architects vs. Urban Forestry

The urban forestry department of many cities recommends a space between trees of between 6 m and 10 m (19 ft and 32 ft). Tree spacing is a function of the size and type of tree. A spacing of 10 m is typically recommended for what one hopes will become large, mature trees. Wider spacing allows crowns to fully develop without competing for sunlight and provides access to more soil.

Toronto: left, Paris: right

Urban Forestry policymakers should allow landscape architects and urban designers some scope with regard to tree spacing. Sometimes a landscape architect’s “design” sense suggests that trees should be planted much closer, such as in the above example from Toronto. The trees are spaced 4.2 m apart. The photo above taken in Paris shows trees that are less than 4 m apart. Landscape architects sometimes want closer spacing so the trunk, as well as the canopy, can spatially define an area around a single bench. The issue of tree spacing can lead to very animated discussions between landscape architects and urban foresters who worry about the maintenance involved with the crowns of maturing trees growing into each other. It seems to me that given the difficulty of growing a tree to any significant stature in the urban landscape, the work of having to prune them should be welcomed.

Tree spacing of 10 m to 12 m for mature trees along a main arterial road designed for cars may be reasonable.

Tree spacing for sidewalks?

Urban Forestry vs. City Storm Water Engineers

The Toronto Green Standard has some very progressive, mandatory stormwater reduction requirements for new developments. Nevertheless, there is an existing policy that is at odds with the effort to reduce the amount of stormwater runoff that flows into the sewer system. The policy also conflicts with another Green Standard objective: to grow large healthy trees in sidewalks to increase the tree canopy.

The policy states that stormwater cannot drain from the surface of a private property across a public sidewalk. Any stormwater that has not been captured must be drained underground and into the storm sewer, meaning stormwater from private property cannot be managed in the public realm.

The rationale for this policy is a large hard-surfaced plaza on private land should not be permitted to have stormwater draining across the public sidewalk and into the street. But this is not the case for the project illustrated here, nor for a growing number of new projects. Requirements for increasing tree canopy and reducing stormwater are generating more ecologically sound projects. Much of the private plaza in this case study is covered by a large well-planted landscaped area capturing much of the rainwater.

The water sheeting down the adjacent private walkway toward the sidewalk is captured by the trench drain that delineates the public area from the private and diverted underground and into the sewer. The policy should be revised to allow for consideration of the context. It is difficult to integrate the various systems needed for Green Infrastructure with “one size fits all” policies. In this example, the water coming down the walkway would have benefited the tree located directly across from it in the public sidewalk.

Private water could have run across the property line to the tree in the public sidewalk

Landscape Architect vs. Architect

Fig. 5 300 Front St.The tree at the end of the row often gets shortchanged in the amount of soil and water it receives. Note the tree on the far left is not getting any water or soil from Silva Cell or the shared planting bed.

Landscape architects and architects must coordinate more if city sidewalks are to become green infrastructure. The coordination required applies from the design process through to construction.

As an example, in Fig. 5, despite being planted simultaneously with the other trees, the tree at the far left is clearly not doing as well. There are a number of reasons for this, including:

- The trees to the right have access to soil and water beyond that of the soil under the sidewalk, from the adjacent planting bed. One option would have been to install more Silva Cells under the walkway to provide all the trees with comparable soil volumes. But that would have required coordination with the architect earlier in the process when the underground structure was being designed. The landscape architect was relying entirely on the soil and water provided under the sidewalk.

- The tree on the left could have benefited from the water coming down the walkway toward it. Instead, the water was intercepted by the trench drain separating the public area from private property. If it were able to drain across the sidewalk, the runoff would have been captured by the passive irrigation system located at the back of the curb. This illustrates the need to revise the policy with respect to stormwater runoff as discussed above.

- The tree to the left, is the last tree in the row. The soil trench created with Silva Cells was designed to extend 3 m beyond the last tree. However, construction on the adjacent building was underway before the soil trench was excavated. The hoarding for the building overlapped the 3 m area intended for the soil trench, making it impossible to construct without removing the hoarding. Resolving this conflict would require a collaborative effort between the architect and landscape architect early on in staging of the construction.

As a result of these issues, the last tree in the line was deprived of water and soil, and it shows. (Fig. 5)

Urban Forestry vs. Everybody Else

The 300 Front stree project provided the opportunity to test out many details that have informed the emerging, new standard, including utilizing a 100 mm trench drain at the back of the curb as a passive irrigation system. There are 60 mm PVC pipes every 2 meters connected to the trench drain that extends under the sidewalk and delivers water into the Silva Cells and the soil. The system doubles as an aeration tube and conduit for fertilizing the tree with compost tea.

The trench drain is a source of endless debate as to whose asset it is, meaning who pays for it and who maintains it? A metal trench drain attached to a concrete curb does not sound like it should be part of Urban Forestry’s portfolio, yet it is very important to the success of trees planted along streets. The lack of clarity about who has responsibility for such a system is one of the many challenges. Many trench drains are filling up with debris and clog regardless of the design because they are not being maintained.

Progress can be slow, but as the 300 Front street case study shows, the 3 C’s of Creativity, Collaboration, and Compromise is a critical step to getting the design right. Stay tuned for the next post on Toronto’s Green Standard Soil Volume requirements.

The grill openings for trench drains should be at right angles to the curb in order to reduce clogging.