In February, the U.S. Forest Service published a report indicating that cities around the country are losing around 4 million trees per year. Of the 20 cities included in the study, 17 showed significant losses of canopy cover, and 16 showed significant increases in impervious hardscape (or paved surfaces that don’t absorb water). At the same time, cities like Los Angeles, New York, Salt Lake City and Philadelphia continue to announce “Million Tree” planting initiatives as part of citywide green infrastructure efforts.

But are these initiatives likely to result in long-term success for urban trees? I’m not optimistic. That’s because we can’t expect to increase canopy cover, environmental utility or tree mortality rates simply by increasing the number of trees we plant — we have to change how we plant them.

Trees are a huge asset to their communities, yet we frequently fail to plant them in viable conditions where they can grow to maturity. Why are mature trees important? As trees grow, they provider greater and greater economic and environmental value, becoming increasingly effective at lowering temperatures, reducing energy costs, enhancing property values and calming traffic. At mature sizes, trees begin to function as meaningful green infrastructure.

For example, a study by U.S. Forest Service researchers shows that a tree with a 30-inch trunk circumference delivers 70 times the air quality benefits of a tree with a 3-inch trunk circumference. Urban trees are a part of almost every development, yet mature urban trees are rare, and might be the most underutilized resource for leveraging maximum value and utility from public spaces.

There can be many reasons why urban trees fail to grow to useful sizes, but the most critical is that they generally don’t have access to sufficient amounts of soil, resulting in a short death and replacement cycle. We remove them — at ongoing expense — before they ever grow big enough to make much environmental or economic contribution. According to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, the average lifespan of a tree in a downtown area is less than 10 years. At a time when we are facing more serious environmental threats than ever before, leveraging the many benefits that trees offer is critical.

Planting trees in conditions that will support long-term growth is the first way in which we need to revise our assumptions about trees as green infrastructure. For trees to live to 60, 70 or 80 years old they need adequate amounts of high-quality soil — around 1,000 cubic feet per tree. Our estimates indicate that trees planted in 1,000 cubic feet of soil pay back their costs after around 20 years. And those trees should be around and contributing substantial economic value for many decades beyond.

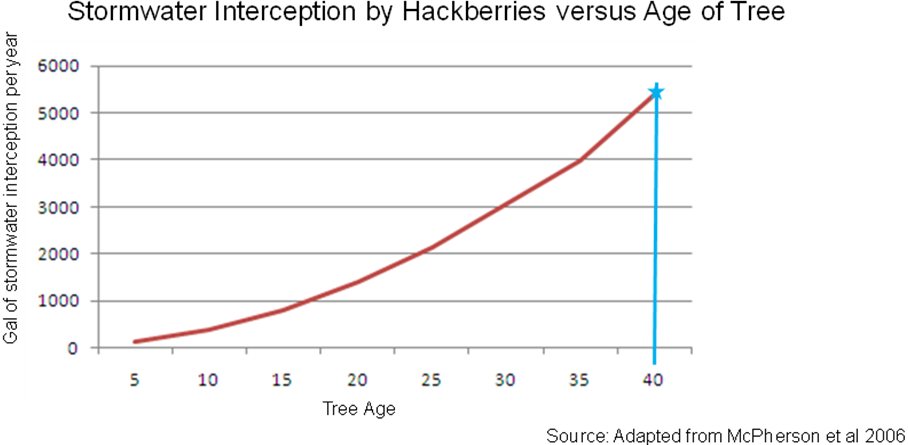

Properly planted trees also play an important role in stormwater infrastructure. This is arguably where they have the greatest value. The soil trees grow in alone is capable of managing rainfall events of up to two inches, which is greater than the average storm event in many places. As trees grow bigger and put out fuller canopies, their capacity to manage stormwater via interception (the amount of rainfall temporarily held on tree leaves and stem surfaces) increases, which can provide significant additional stormwater benefits beyond storage in the soil.

I’m not trying to pick on Million Tree initiatives. Garnering public support and involvement in tree planting is an important part of the long-term success of the urban forest. My point is simply that we need to pay attention not just to quantity of trees, but to quality andperformance. That must start with ensuring that they have access to adequate soil volumes, even in paved areas like sidewalks, parking lots and plazas.

Some cities across North America are beginning to address the problem of in adequate planting conditions by setting soil volume minimums for street trees. Toronto, Ontario has the most ambitious program: Their Green Standard calls for street trees in shared soil volumes to receive a minimum of 15 cubic meters (529 cubic feet) per tree, and for single trees to receive a minimum of 30 cubic meters (1,059 cubic feet) per tree. The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, Athens-Clark County in Georgia, Markham, Ontario and the Denver Parks Department are some of the other municipalities that are setting soil volume minimums to ensure the long-term viability of their trees.

We make massive investments in “gray” urban infrastructure features, like pipes and light poles, with the expectation that they will perform as efficiently and effectively as possible for decades — even though they lose value as soon as they go online. Trees work in the opposite way and require us to plan a little differently, yet the potential payback is enormous. Designing conditions for trees to grow and thrive in urban areas will significantly leverage their value and effectiveness to the community at large, and we all stand to benefit.

This post originally appeared in Next American City.

Douglas Adams: “Life… is like a grapefruit. It’s orange and squishy, and has a few pips in it, and some folks have half a one for breakfast.”