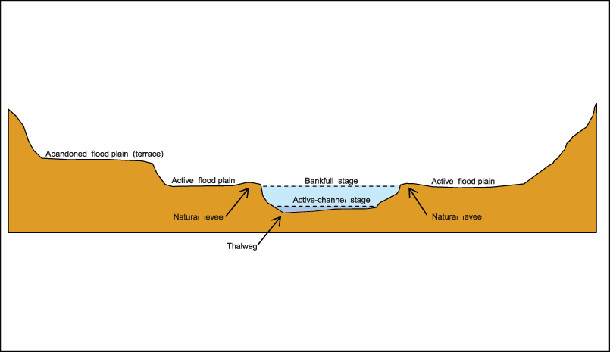

A diagram of the cross-section through a stream channel and its adjacent components. This system, not just the stream channel itself, serves to process water from the surrounding landscape in varied methods. These methods for processing water are redundant, and this redundancy provides for back-up when failure of a single system occurs, ensuring that the failure of one part does not equate to the failure the whole system.

Photo Source: USGS

(Read “Rise of the Curb Cut: Part 1 here).

The fundamental behavior of stormwater in curbs and street design is simple. Each creature, each inanimate object, each molecule of everything functions and abides by its simple and powerful law every day: gravity. From this basic concept, direct parallels can be drawn between the design elements of streams and the design elements of streets.

Banking on Change

In channels, flow occurs between the two edges, called banks. When the channel is full to the edge of these banks, we refer to the condition as “bankfull,” or the maximum capacity the channel has to contain flowing water. If even one more drop hits the channel, the capacity is exceeded and the channel then extends itself into the overflow conditions into the surrounding area referred to as the floodplain. The floodplain serves as an accessory to the main channel, allowing it to expand into this area when necessary rather than causing catastrophic and uncontrolled flows in unanticipated areas. Floodplains also provide a large amount of infiltration and groundwater recharge, abundant growth of vegetation due to increased amounts of water distinct from the uplands, and a place for debris to be deposited due to decreased energy of flow in these areas.

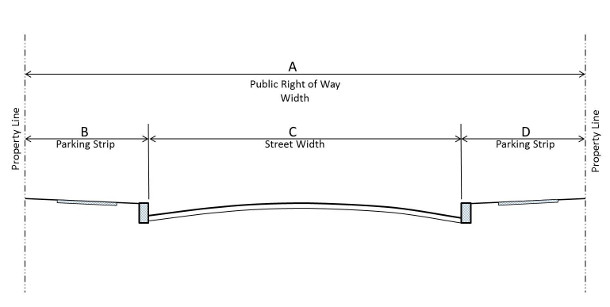

A typical curb-and-gutter street section, showing the street, crowned to move water away from the center to the curbs at both sides. The “parking strips” show sidewalks on either sides for people to move about away from the flow of traffic and stormwater functions. The entire section is efficient at moving water yet impervious, with no place to accept and treat stormwater except in sewer infrastructure below.

Photo Source: CA-elcerrito

Street sections and curbs match the form and function of natural channels in some important ways. The curb acts as the bank, containing the flows. The street and curb serve to create the channel at bank full. The street and curb act as a standalone system, however, without any floodplain for overflow. Excess water often goes into a storm sewer – another effective stream channel – and downstream until reaching the receiving waters of a major lake or river.

The additional functions of the floodplain – water purification through soil and plant interaction in the profile, sediment reduction, and provision for passive watering – are forgotten in urban streets. The dynamics of the overflow conditions and expansion of the channel under those conditions are difficult to understand and predict, and they are often minimized in the design process. Whereas there was space between structures and populations in rural environments that could accommodate unpredictable water flows, the tightly-confined nature of the urban areas make unpredictable water flows a potential liability. This is especially true because many people believe stormwater is unclean.

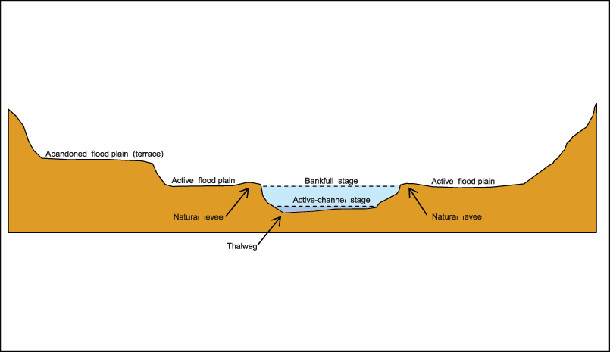

Stormwater finds its way to areas outside of the street into planters as seen here. In order to bring water into these areas, the adjacent curb is removed and replaced with an inlet – the curb-cut – seen in granite above. This curb-cut directs and accepts water into these areas at lower levels of flow as it moves along the gutter. At higher levels when standing water in the planter will not allow any more water to enter, the flow along the curb bypasses the curb-cut and continues downstream.

Photo Source: The Intertwine

The most important difference between natural river channels and urban streets lies in the response of the system to changing environmental conditions. Whereas a stream responds to environmental conditions specific to its unique environment and evolution, streets and curbs are designed from a template of materials non-specific to environmental conditions other than the size of a given volume of water (or storm event). These designs often neglect to answer the needs of the adjacent areas for groundwater recharge, vegetation watering, nutrient provision, evaporative cooling , and the people living there.

Bringing Water In By Letting Water Out

Recently, designers, citizens, and policy-makers have all started to recognize that rain water and gray infrastructure like sewers, curbs, and sidewalks don’t need to be kept separate – and in fact that there are advantages to integrating them. Special places have been designed to receive stormwater from the street, gracing the once dry areas with free irrigation and fertilization. The curb-cut is a break in the continuous height of the curb where stormwater running aside it may be released from its channel into a neighboring area. These areas are often vegetated and sized to hold a certain volume of water in the spaces between the particles of soil. The street channel, through the rise and fall of the curb via the curb-cut, now has access to a floodplain.

Stormwater is diverted into the planters via grated curb-cuts for a pedestrian-friendly surface. Water that enters the planters is available for uptake and use by the plants via evapotranspiration, cooling of surfaces, and pollutant removal through movement through the soil profile.

Photo Source: Carbon Talks

This unique and simple device is designed as an off-line or a bypass system, a bonus area for stormwater before it reaches an inlet to the storm sewer. Curb cuts provide a passage for water to leave the street at low flows, but once the capacity is reached in the storage area of the planter or tree opening, the water continues on its journey along the curb as it once was.

Curb cuts are easy to create – just cut and remove a section of curb and replace it with a concrete curb-cut poured in place. With this simple addition, the once-lost functions of the floodplain have rejoined the street “channel” to provide water, nutrients, cleansing, and reduced energy, and evaporative cooling to adjacent areas. In fact, curb cuts also soften and expand the banks and floodplain of the street by bringing water into the landscape beyond.

As we saw in part one of this series, the curb was created to protect the health of city dwellers at a time when municipal standards for waste removal were still unaddressed. It prevented the return of contaminated water from the streets back into the places people lived. As sewers, waste, and water treatment have improved, the quality of stormwater in the streets has too. Rejoining urban hydrology across the curb through the curb-cut might be only the beginning. We can use the framework and our understanding of curb cuts to design the urban landscape to bring water into our lives by letting water out of the street.

Andrea Wedul is a Graduate Landscape Architect with The Kestrel Design Group.

Sources Cited

Louis, G. E. (2004, August). A historical context of municipal solid waste management in the United States. Waste Management and Research (via PubMed.gov), 4, 306-322.

Wikipedia. (n.d.). 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak. Retrieved April 13, 2013, from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1854_Broad_Street_cholera_outbreak

I really like the idea of using excess water from the street to water planters along the side of the road. I don’t think it happens much where I live, but I may have to write the city about it. Anything that will help make the city greener is a great idea in my book. Especially when it is as easy as cutting a few gaps in the curb.