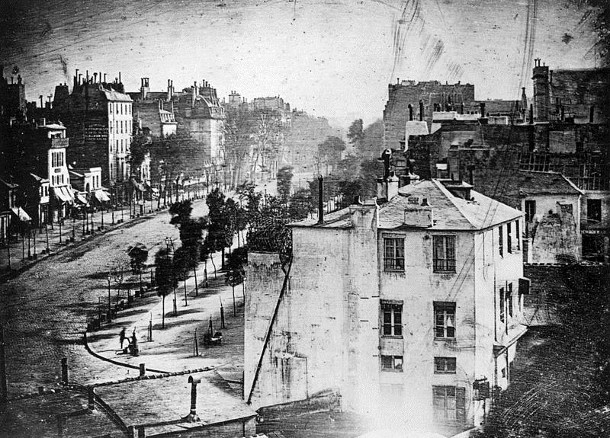

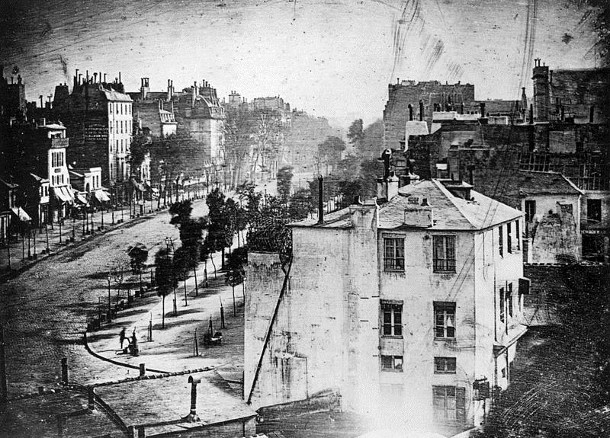

This image is borrowed from the Boulevard Temple daguerreotypes, taken in 1838 by Daguerre. It is the world’s oldest known photograph, depicting people and street trees in Paris at that time. Three rows of young trees are visible (some damaged), and these were some of the trees that would later grow into the trees that enlivened the French Impressionists paintings of Paris’s street scenes of the 1870’s & 1880’s. Image: Wikipedia.

The remaking of Paris fell squarely onto the shoulders of Napoleon I’s grandson, Napoleon III. Napoleon III accepted his new position as Emperor when huge Parisian riots erupted in 1848, and removed the latest crop of monarchists and put the Bonapartes back on top. Unlike his grandfather, Napoleon III had a real flair for remaking Paris. He hired Baron G.E. Haussmann from Bordeaux in 1853 to assist him with the job.

Haussmann was charged with many noble goals, such as letting Parisians drink cleaner water and breathe cleaner air. The Emperor also emphasized the importance of wide, oblique, angled streets, centered between train stations for rapid troop movement, with clear lines of sight for heavy artillery to put a stop to further riots and barricades that might remove Napoleon III from power.

Baron Haussman proved instrumental in effecting these streets. The Baron’s home city of Bordeaux had been remade by the Marquis deTourny; who was a royal intendant to King Louis XV in the 1740’s and 1750’s, a time in which Bordeaux created a vast network of tree-lined boulevards, treed places, and a city-wide encircling green corridor. deTourny was both visionary and hard-headed enough to override the local authorities, who bitterly fought his aforementioned “greening” plans for Bordeaux. A century later, deTourny’s mentee, Baron Haussmann, learned the importance of “making no small plans” for Paris, as Walter Burley-Griffin would later say for Chicago in the 1900’s.

Baron Haussmann appointed some great people to his charge, and his team got to work. In a mere 17 years (1853-1870), they demolished the old network of city walls, converted them to tree-lined boulevards, and removed about 60 percent of the old city. For good measure, they also doubled the size of Paris while they were at it. I counted 20 major straight boulevards, some running for miles, that Haussmann inserted into Paris. Many of these were up to 100 feet (30 m) wide. The boulevards laid out by Baron Haussmann were lined with pollarded trees which were heavily pruned every year, a maintenance regime which kept these trees in perpetual adolescence and allowed them to exist with much smaller soil volumes. I should also note that Haussmann’s team created building setbacks, and hundreds of blocks of solid stone buildings using a spectacular design template.

Today these 2nd Empire buildings with mansard roofs, wide boulevards, round-a-bouts, and voluminous numbers of trees are the face of Paris projected around the world. Fashion had come full-circle, and the promenading aristocratic alles of Queen Marie Medici and Louis XIV in the 1600’s were now the tree-lined Parisian boulevards provided for the general public and the merchant bourgeoisie to gather, recreate and enjoy. It all cost what critics called, “the outrageous sum of 2.5 billion francs.” To me, these incredible tree-lined boulevards are reflective of what a Bilbao city councilman said when asked about Frank Gehry’s globally-famous Guggenheim Museum: “It cost us a lot of money, but for what we got, it was cheap.”

Ile Saint Louis is the smaller natural island behind Ile de Cite shown in the foreground [you can see Notre Dame on the right]. The Seine River goes around on both sides of the island. This is the center of Paris. Image Source: Swede

An absolutely incredible image from Airpano (2010). They shoot 360 degree panoramas of great cultural and natural wonders of the world. This starburst image captures Paris with its tree-lined boulevards radiating from the Arc de Triomphe. An image that encapsulates the phrase, All roads lead to Paris, and reinforces Paris as a City of Trees, in addition to its more famous moniker as the City of Lights. Image: Air Pano

L. Peter MacDonagh, ASLA, is the Director of Science + Design The Kestrel Design Group.

Bibliography:

Lawrence, H.W. 2008, City Trees: A Historical Geography from the Renaissance through the Nineteenth Century.

Mercier, L.S. 1782. Tableau de Paris.

That picture labelled “Champs-Elysee” is really the Avenue de la Grande Armée. It is the “continuation” of the Champs d’Élysées on the western side of the Arc de Triomphe. Other than the absence of the Arc from the photo (indeed the photo may be taken from the top of the Arc?) one can tell by that high-rise building at centre-right which is the Palais des Congrés at Porte Maillot (over the Perihperique freeway).