OpenTreeMaps are collaborative, crowd-sourced projects where citizens help inventory urban trees, learn about the environmental benefits trees provide and explore nature in their city. Kelaine Ravdin, owner of Urban Ecos, has worked as the project lead on OpenTreeMap projects across California, including Sacramento, San Francisco, San Diego, and Los Angeles. Kelaine’s work blends a deep understanding of urban forestry with current mapping and data tools. I spoke to Kelaine about her experience using open data, working with cities, and what tree inventories of the future might look like. Our conversation has been edited and condensed. –LM

Tell me a bit about your background.

It’s a bit helter-skelter! I shifted from fauna—a pre-vet Bachelor’s degree—to flora by pursuing a Master’s degree in landscape architecture with a minor in forestry. I spent some time in Berlin as a Fulbright Scholar studying urban ecology and design and then came to California to work with the US Forest Service’s Center for Urban Forest Research, doing research into the benefits that urban trees provide. After a few years, I decided to branch out on my own as an urban forestry consultant and started my company, Urban Ecos.

How did you get involved in the Open Tree Map?

About seven years ago, San Francisco’s Friends of the Urban Forest (FUF) won a grant to build an open tree map to crowd-source a tree inventory for the city; I was hired as a consultant to be the project lead. We launched the project about two years after receiving the grant, in 2010.

Right after we launched, a company called Azavea got in touch with us; they had just gotten a grant to build an open-source citizen tree mapping project! Given that we had so much overlap in experience and in what we wanted to achieve, we ended up collaborating so that Azavea could build on what FUF had created. That became the Philly Tree Map.

Did you become an open tree map expert?

Hah, well, not exactly – I’m still more the a tree person than a software person. But it did lead to me being hired as the project lead for the greenprint map in Sacramento and then the San Diego tree map and then the LA tree map.

Are all open tree maps now built using Azavea’s software?

Well, one key thing about OpenTreeMap is that the code is open source, so the software doesn’t really belong to anyone. The main contributors have been the developers I worked with early on—Umbrella Consulting—and Azavea. But in an open source project anyone can download and make use of the code and build new features.

That said, Azavea has done the bulk of the work on the OpenTreeMap software. They’ve just released a huge new update, OpenTreeMap 2.0 that really makes use of the improvements in technology that have taken place in the last five years. And they’ve shifted the project to a subscription model to make it easier to get started.

Open Tree Map projects all seem to require coordination between several different agencies (non-profits, cities, grant agencies, etc.) How does something like this get off the ground?

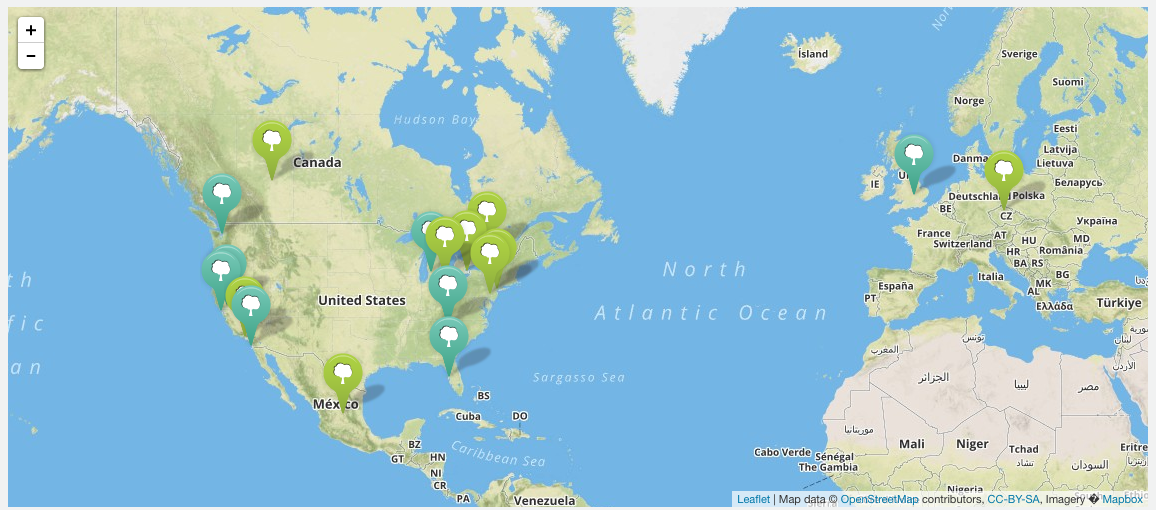

My experience is entirely with California maps, but there are now maps all over the country and in Canada, England, and Mexico. Even in California my experience has varied quite a bit, but there has been one commonality: every project has a champion. This person is the driving force to get the grant, hire someone to lead the project (like me!) and see the whole thing through.

How long does it take to set up an Open Tree Map?

It’s getting faster and faster. The first time we did it, in San Francisco, it took about two years to complete the project. By the time we were setting up a map in San Diego several years later the turnaround time was down to just six months. Now, with version 2.0, you really can get started in just minutes.

Is there ongoing tech support? Once everything is set up, how does it get maintained?

Maintenance has changed as the technology has developed. OpenTreeMap 1.0 was expensive to set up, but had no subscription fee (it also had no updates). With the release of Azavea’s version 2.0 there is a subscription model, so depending on your needs you pay a flat monthly fee that gives you a set number of features, a certain number of trees, and software updates.

But isn’t it open source? Why pay?

It is open source, and the code is there for anyone to build and create their own map, but it’s not a turn-key operation. Anyone considering setting up an open tree map for their city should know that it requires technical experience and money to make something truly functional.

What is your vision for this platform?

My hope was always that open tree maps could help a broader audience to understand and appreciate with the urban forest – something they could dip into to get information about a tree or add the one next to them at the bus stop, and dip out of just as easily. In other words, a way to interact and help that wasn’t a big, intense field operation. My feeling is that you shouldn’t need to be an urban forest evangelist to participate. I want everyone to be able to participate easily.

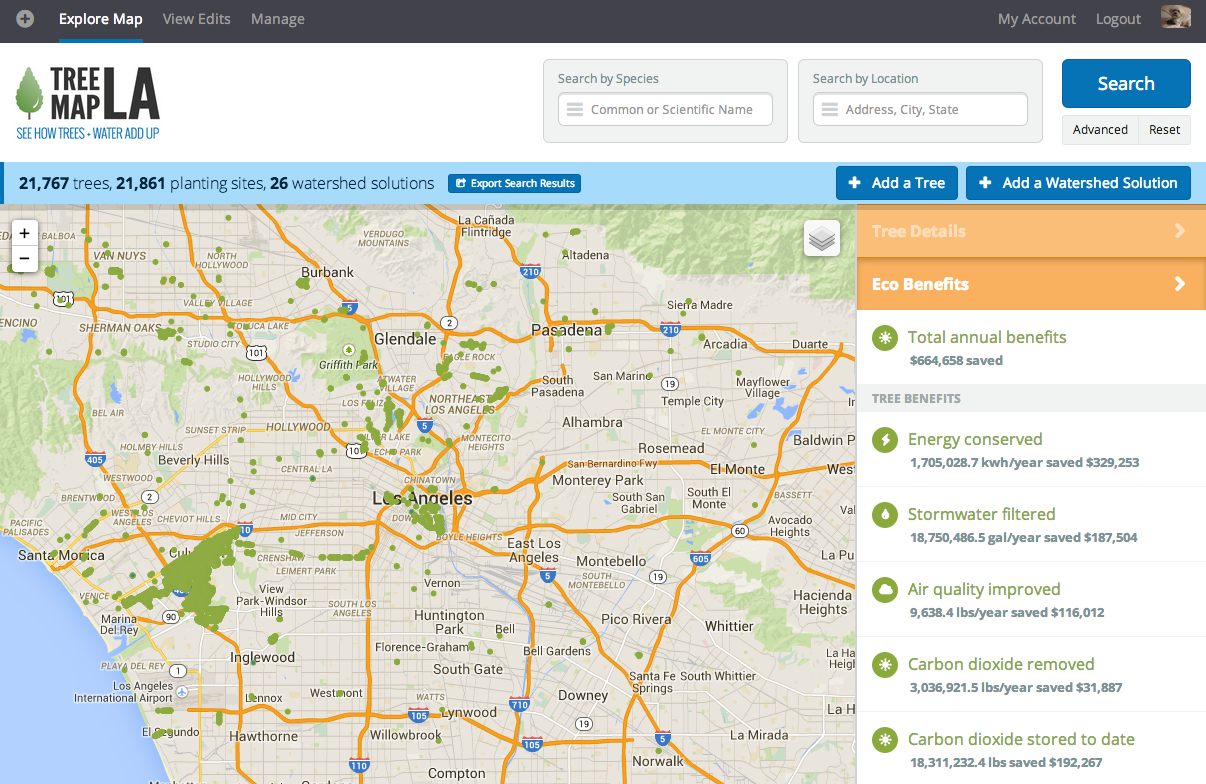

Los Angeles has done a great job promoting this message and doing public outreach for their open tree map. They have a lively Facebook and Twitter presence and do events where people get together to map trees in a neighborhood for a couple of hours, and then sometimes drink a beer together in the neighborhood pub!

What are some of the goals cities have for their open tree maps?

Actually, in my experience it’s never been the city driving the effort – it has always been a partnership with a non-profit that advocates and is at the vanguard. The most the cities have been willing to do is agree to share existing inventory data during the initial setup projects and to consider using the data that the map compiles. We have yet to connect a public map and a city database; although in fact, there are security measures in place so that public input doesn’t contaminate official city data. In my experience, cities are still pretty slow-moving and tech-averse.

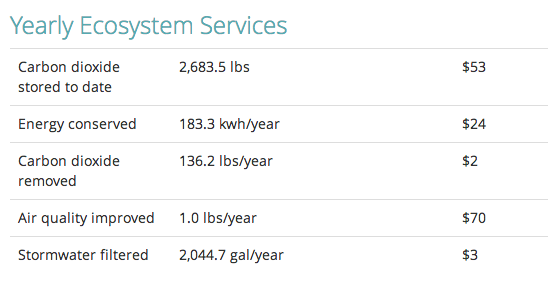

All the maps display urban forest “ecobenefits.” How are those calculated?

The eco-benefits are calculated using i-Tree, the software developed by the US Forest Service.

What are the advantages of an open tree map compared to a traditional tree inventory?

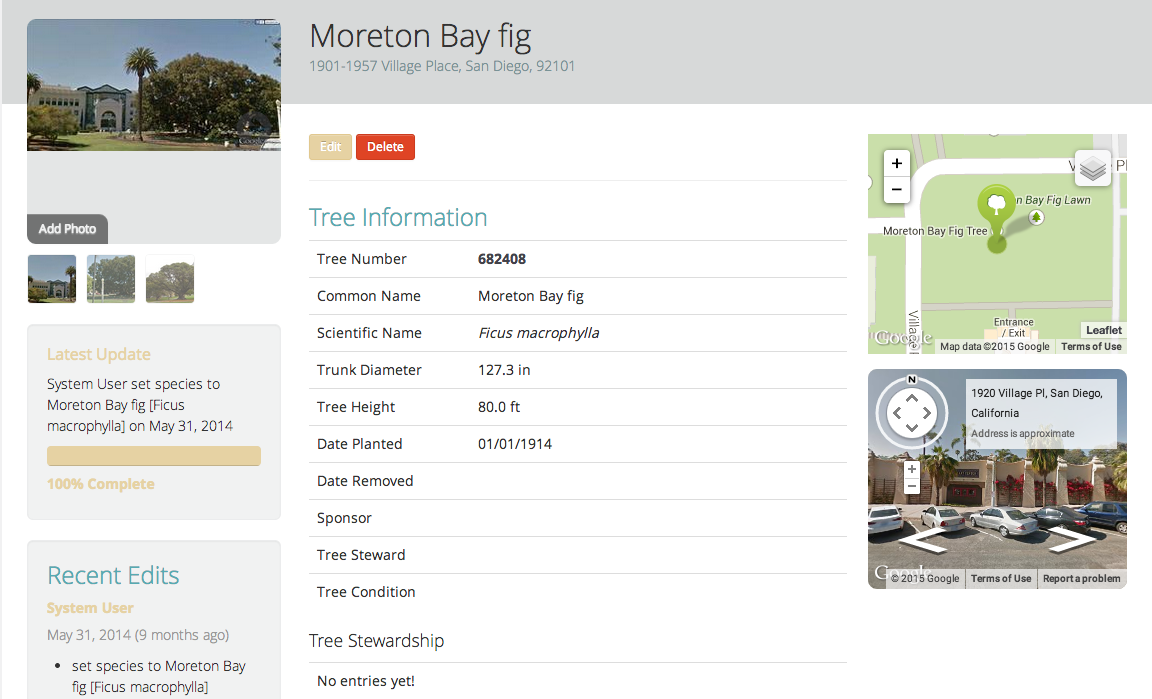

I think of it more as a supplement to a traditional inventory rather than a replacement. But one of its biggest advantages is the living nature of an open tree map.

If you look at San Francisco’s current inventory, you will see a lot of trees that are 3” in diameter but that were planted 20 years ago… the inventory just hasn’t been updated in that time! Cities spend a lot of money on doing a tree inventory, which is a useful exercise, but it’s only a snapshot. There is often little money or manpower to update the inventory regularly. In a perfect world an open tree map would enable the public to help keep the tree inventory current.

These maps seem like great tools to help inform effective urban tree management, care, planning, and policy.

That’s really important. There is no reason a tool like this couldn’t be used to influence planning, species selection, care and maintenance, and policy.

Another big area an open tree map can contribute is providing a platform to map trees on private property. These are trees which would otherwise never be inventoried because of the expense and the intrusion, but that can nonetheless be a major contributor to the overall urban tree canopy. Any time we get a better picture of what’s happening on private property, it helps us make better public decisions.

Better care of the WHOLE urban forest is the goal. We can’t do any of that without an accurate inventory.

Are open tree maps ever completed?

Never. By nature they are ongoing, and with good reason. From a science perspective, we always want to incorporate new data. Also, trees are living, changing, and growing. If a tree inventory contains current information it means we understand their impact much more accurately.

Accuracy with volunteer data is always an issue. How do manage that?

I was concerned about the same thing, so I did a small, informal assessment after launching San Francisco’s open tree map. What I found was that there were a few different categories of errors that we could help manage by adjusting the user experience.

For example, geolocation using an address is the easiest way to add trees to the map, but it’s an imperfect tool because geolocation just drops the tree in the center of the parcel, usually the roof of a building! Users need to then drag the tree to the right spot. To manage that issue, we added a warning within the map reminding people to drag them away from the center if they hadn’t. We expected species identification to be the biggest problem, so we didn’t make that field mandatory. Instead, we added an option to allow people to enter partial information such as, “I know it’s a maple, but I don’t know what kind.” While this isn’t perfect precision by any means, it does give you a general sense of what to expect from that tree.

Trees with a serious error – wrong size, wrong space, wrong species – were very rare, probably less than 10 percent. So people really outperformed my expectations. They didn’t feel pressure to guess at things that they didn’t know.

The data on these maps is far from perfect, but is the best science available to us and is defensible on air quality benefits, water quality benefits, and other environmental effects.

How would you like to see this project change and grow over the next decade?

One of my hopes was to be able to add other urban nature to the map, such as creek beds, butterflies, birds, etc. This still lies in the future, but the Los Angeles map has added a feature called “Watershed Solutions” that tracks the impact of tools like rain gardens and rain barrels. So far 26 of these “solutions” have been added, and the city has agreed that they would use the map tool to document their success. There is so much more room to collaborate and work with cities to make the care of trees more effective and efficient. I’m excited to watch that develop.

Thanks, Kelaine! Kelaine Ravdin is the founder and owner of Urban Ecos.

Leave Your Comment