We all know that street trees have value; you frequently hear statistics about how much energy savings they offer, or how much they add to the selling price of a home. And in some cases, for example with heritage trees or in environmentally sensitive areas, trees are identified as assets for planning and permitting purposes. Yet the larger urban forest, that interconnected population of trees in the built environment, isn’t recognized as an asset on city balance sheets – where the real work of budgeting, financing, and accounting gets hashed out. But that may be changing.

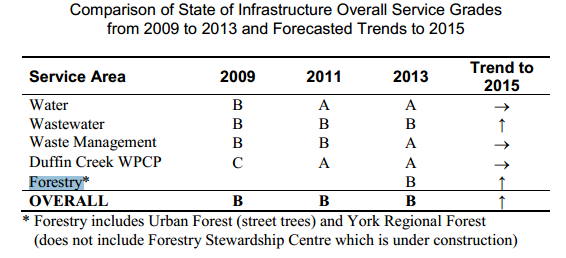

The Regional Municipality of York, Ontario in Canada officially included “Forestry” (both street trees and regional forests), as an asset group in their Environmental Services 2015 State of Infrastructure Update Report. Including Forestry in their infrastructure report is a formal recognition that trees provide actual, measurable value that requires maintenance and management. With this move, the urban forest joins more traditional infrastructure line items such as waste, wastewater, and waste management on the region’s balance sheet.

The definition of an asset

In accounting terms, a government asset is defined as the following: “[t]hat government must control the future economic benefit associated with the asset to the extent that it can benefit directly from the asset and generally can deny or regulate access to that benefit by others.”

In 2008 the Canadian Federal Government mandated that all public entities (such as cities, universities, and regions) must treat their assets the same way that the private sector does – by placing a dollar value on the asset and depreciating on the balance sheet over time. This mandate meant that all entities were required to create Tangible Capital Asset (TCA) reports as well as internal Municipal Performance Measurement Programs (MPMP) that provide an evaluation of the state of the asset based on standardized benchmarks. (Read more here for a good overview of these two programs).

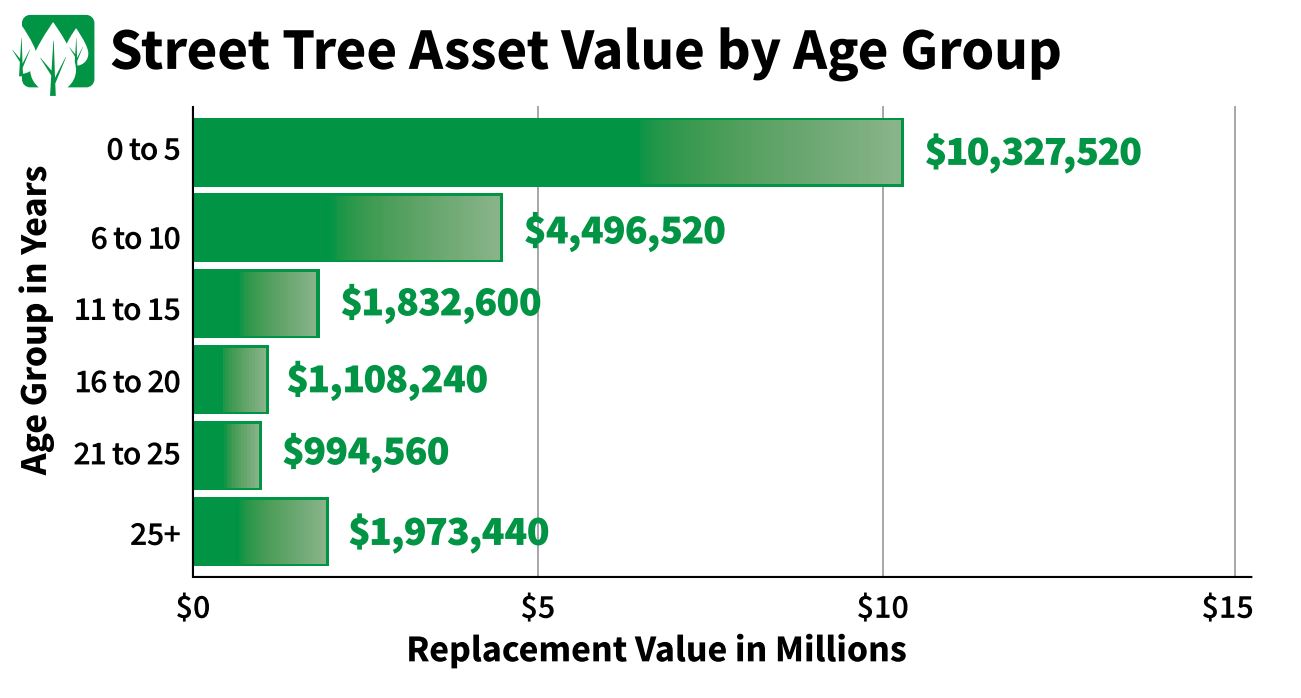

As prescribed by the Public Sector Accounting Board, Tangible Capital Assets (TCAs) do not include biological items like trees, but York Region wanted to be able to create asset reports for their urban forest so that they could measure their performance, include them in budgeting, and assess their own internal performance managing them as a resource. For these reasons, they decided to include the urban forest in their Municipal Performance Measurement Program (MPMP). Urban trees are still not formally TCAs, but York Region is treating them as such for the purpose of the performance program, and includes them (and other biological assets) when preparing their state of the infrastructure reports.

The significance of including trees in the MPMP program

Treating trees as assets for the purposes of the Municipal Performance Measurement Program achieves several important goals:

- Recognizes real value: puts the value trees provide where it really matters — on balance sheets.

- Creates metrics: requires measurable areas of performance and consensus/recognition of how that is defined and achieved.

- Justifies budgets: justifies an adequate installation and maintenance budget to ensure that the asset is being managed properly.

Treating trees as assets increases the clout and influence of urban forestry departments tremendously, repositioning them as the owner of a large and growing asset class. This gives new value to street trees and provides a regulatory requirement to manage their value.

I asked Jess Vogt, an assistant professor at DePaul University who has studied the cost of maintaining (and not maintaining) urban trees, about the idea of making forestry an infrastructure asset class. She said, “It’s a fascinating idea. And it seems like it would be a great thing for cities to do because it would help them realize that they need to spend money maintaining trees in the same way you need to spend money maintaining bridges and roads.”

She continued, “One of the things that we’ve come across in looking into municipal budgets and what cities do spend money on in terms of trees is that they spend limited money on maintenance in the best of circumstances, and when there is any kind of fiscal crisis tree budgets are the first to go. They are considered optional. Not planting more trees in one thing, but not maintaining existing trees for safety is quite another because they may become at risk if they are not maintained. I think that if they were an asset class it would put trees into more serious consideration.”

Classifying the urban forest as an asset doesn’t solve all the challenges of creating a mature tree canopy in the built environment – there are still the problems of providing adequate available soil volume, soil compaction, construction practices, and poor nursery stock, to name just a few. But it’s a great start.

First in class

To our knowledge York Region is the first jurisdiction in North America that has applied this process to the urban forest. If more urban forestry departments follow suit, it will be easier to refine these standards and accelerate the benefits of including the urban forest in the Municipal Performance Measurement Program (MPMP). The MPMP is internal to each municipality and therefore gives more leeway about what assets the performance measurement is applied to. The Tangible Capital Asset (TCA) program is reported directly to the Provincial Government and has a federal counterpart as well.

York Region’s move to recognize forestry in the MPMP came about after their Urban Forestry department was put under the Environmental Services department. With the support of the department’s senior management, who recognized the capacity of green infrastructure and the role it can play at the city level, it was mandated that their internal MPMP process include urban forestry.

An external consulting firm was hired to work with region staff to do the asset evaluation. All other assets, such as waste water facilities, had values and standardized benchmarks that they could be evaluated against. None of this existed for urban forestry. While trees provide many real services, since they had never met the traditional definition of an asset the urban forestry group had to develop a new template that would work.

The Region and the consulting firm turned to existing research to evaluate the state of the urban forest. To do this, they asked questions like: was there a work order system in place to capture and measure work? Was maintenance reactive or proactive? Were there adequate budgets to do the needed work? Was there a system in place to measure what work was needed? Were there standardized practices to evaluate if the work was being done efficiently?

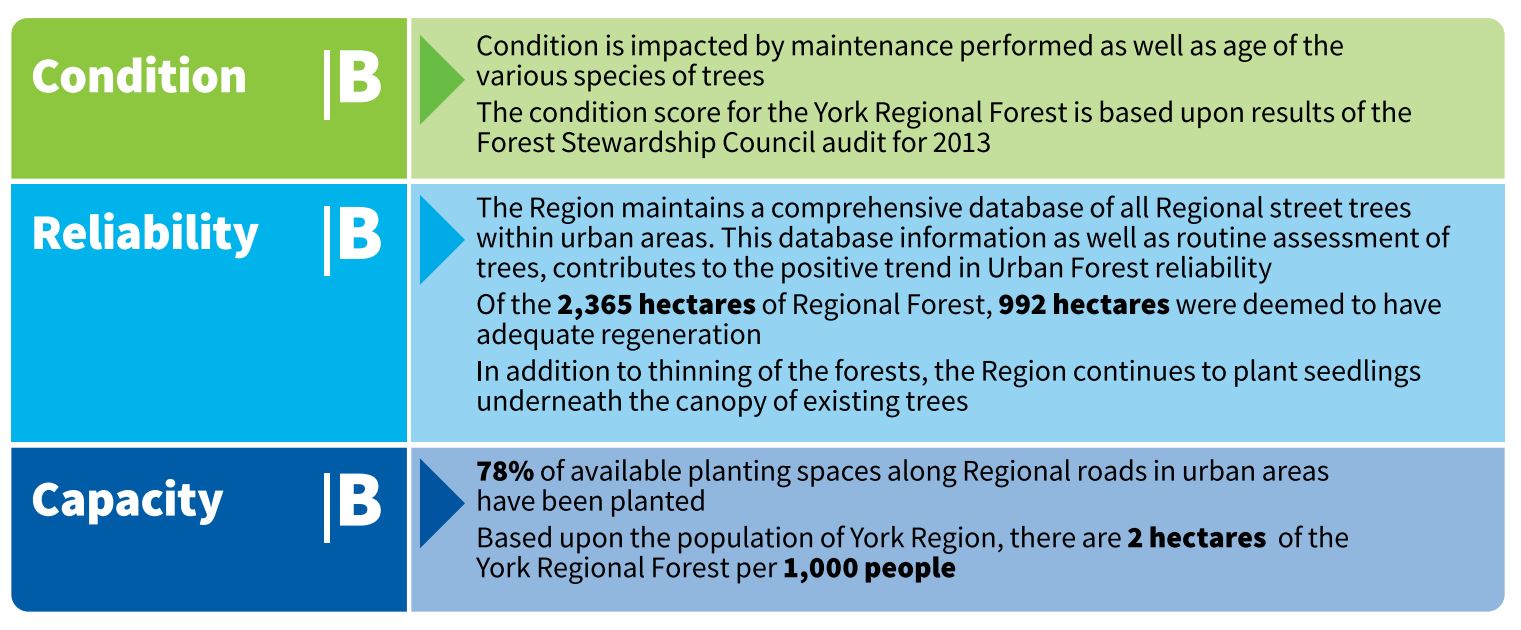

As part of the process they developed a number of key performance indicators. For each asset class they have three dimensions: reliability, capacity, and soundness. Each dimension has measures (ex. resilience to weather and disease, size, age, stocking rate) and each measure has indicators (ex. species diversity, # of street trees by diameter class, tree space available).

All of this was aligned with criteria for creating an overall rating for the state of the urban forest. There are also a series of benchmarks so the Region can evaluate progress toward their goals of increasing urban tree canopy cover and successfully manaing the urban forest as an asset. This process was not designed to put a dollar value on the asset the way i-Tree does; instead it evaluates the state of the asset and whether it is being managed properly.

York Region had little information to work with in order to create their asset evaluation, so the process for creating this system for managing their urban forest was no doubt challenging. But it is an exciting first step. The final version is published and the executive summary is publicly available on the York Region website (pages 25 and 33).

Recognizing the urban forest as an asset class doesn’t eliminate the need to have all kinds of other policies around tree care in place. But if we can become more sophisticated in how we capture benefits – and assign budgets – it could have a positive impact of the overall level of professionalism and practice in the industry, create a mechanism to generate more funds to meet these benchmarks, and standardize practices and create more funds for research to prove out best management (BMP) applications. Above all, this combination of factors has the potential to significantly raise the perceived value of the urban forest for decision makers – that’s a value that is hard to estimate.

Do you live in a city or town that recognizes urban trees as an asset group? Please write to us at [email protected] and let us know!

Special thanks to James Lane (York Region), Lara Roman (U.S. Forest Service), Jess Vogt (DePaul University), and Terrence Chen (Michael Baker International) for their contributions.

References:

Vogt JM, Hauer RJ, Fischer BC (2015). The costs of maintaining and not maintaining trees: A review of the urban forestry and arboriculture literature. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 41(6): 293-322.

York Region State of Infrastructure Report, 2015.

I think it’s a great idea to have these areas classified as an asset. Trees are not just beneficial to the environment, they contribute hugely to the wellbeing of people. Most of us would far rather look out on some greenery than at concrete. It’s a shame that precious woodland needs to be assigned a $ value, but if that helps to get money spent on our trees, then it can only be a good thing.