If you work with trees, you know how important soil is. Understanding a site’s soil is key to plant selection, amendment recommendations, and maintenance planning. But soil science is complex, and analysis takes time and money. Here are a few considerations to help make soil assessment more efficient on a budget.

Divide and conquer. Even on a small site, don’t assume that soil is the same throughout. Topsoil may have been removed in some areas, fill soil added in others. Usage can change the soil properties as well; a footpath, a lawn and a natural area are likely to have different chemical makeups and levels of compaction. As best as you can, divide the site into “zones.” For example, an area that has been graded or disturbed would be a separate zone than one that has been undisturbed. Collect samples from each of these zones for analysis.

Take an average. If you are testing for horticultural properties such as texture, pH, or nutrient levels, take multiple sub-samples from each zone and blend for a representative sample of that zone. Sub-samples should come from the top 6-8 inches of the soil, excluding mulch or other surface organic matter. You will want to end up with 2-3 cups of soil per zone, some to analyze on site and some to send for lab analysis if desired.

Take an average. If you are testing for horticultural properties such as texture, pH, or nutrient levels, take multiple sub-samples from each zone and blend for a representative sample of that zone. Sub-samples should come from the top 6-8 inches of the soil, excluding mulch or other surface organic matter. You will want to end up with 2-3 cups of soil per zone, some to analyze on site and some to send for lab analysis if desired.

Digging is also analysis. You can find out a lot about the soil with just your muscles and low-tech tools such as a shovel or soil probe. While you are collecting sub-samples, pay attention and make note of the following:

- Color of soil

- Ease of digging or probing and at what depth this changes

- Moisture levels at varying depths

- Presence of roots (live or dead) at varying depths

- Presence and identification of living plants – weeds or otherwise

- Indicators of disturbance such as construction debris, poor quality fill soil, absence of roots where roots should be present.

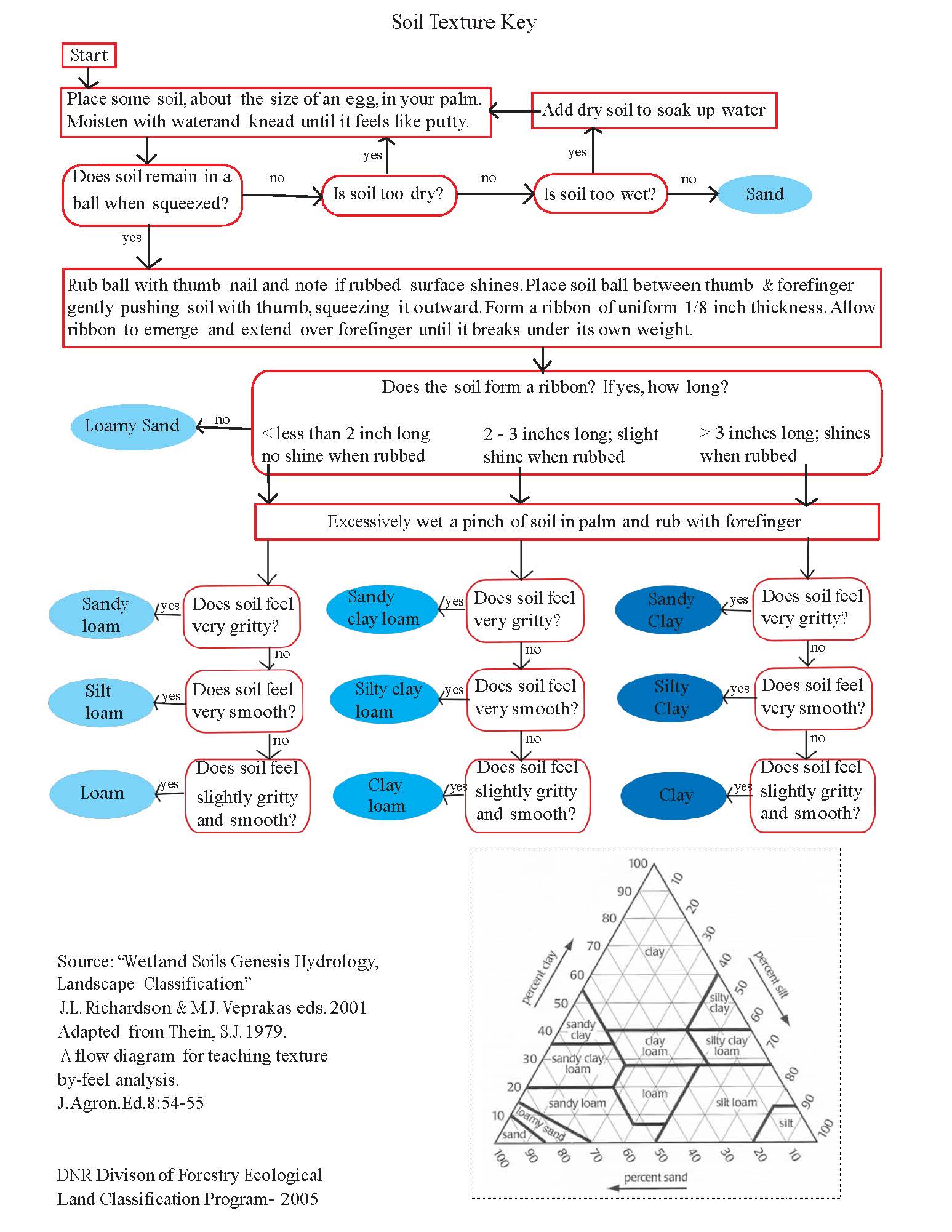

Get your hands dirty. Soil texture is one of the most important factors to analyze, as it will affect so many recommendations. While a soil lab can analyze soil texture, you can do this on site for free. There are many online flowcharts explaining the “Soil Texture by Feel” method, below is one of my favorites.  You can also analyze soil structure – how it hangs together in aggregates – with a simple field test described in this article.

You can also analyze soil structure – how it hangs together in aggregates – with a simple field test described in this article.

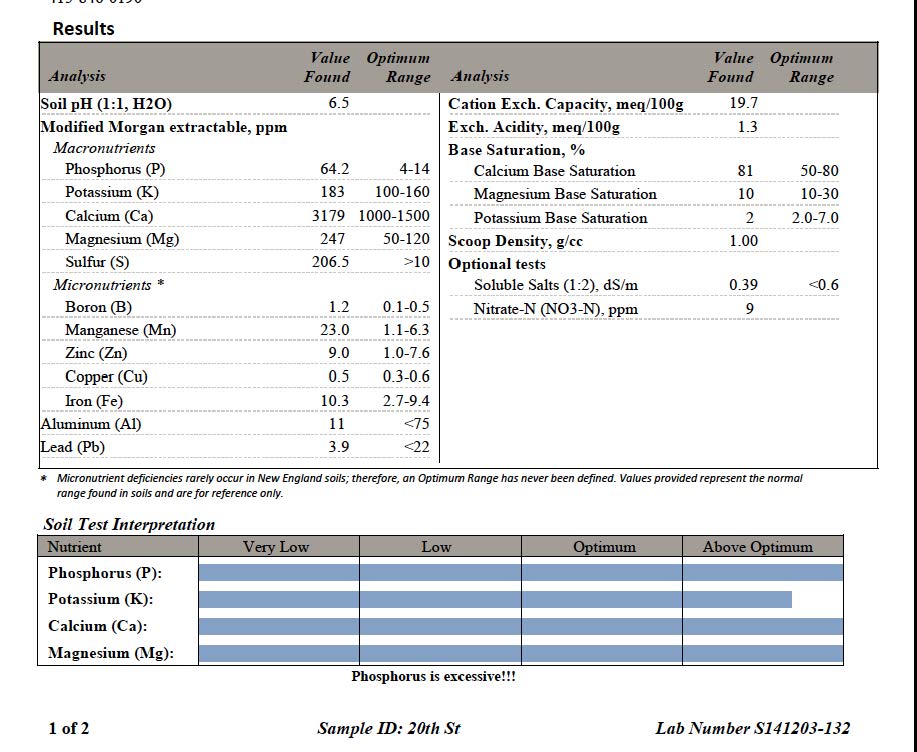

How a soil lab can help. Although you can test pH and nutrient levels on site with field testing kits, a lab can provide a report with recommendations for amending soil based on what you want to grow there. The lab can also tell you whether the site’s nutrient levels are considered optimal, excessive or low, but beware – ideal nutrient levels are based on regional norms. If you use an out-of-state lab, you run the risk of getting inaccurate recommendations.

I live in California, where expensive commercial labs are the only option for soil testing. For clients on a budget, I sometimes send soil samples to University of Massachusetts for fertility analysis. I’ll never forget one of my first reports from UMass warning me that “Phosphorus is excessive!!!” in my sample. (They really used three exclamation marks). The site was an urban sidewalk garden with a (mostly) thriving palette of native and climate-appropriate plants. Alarmed, I contacted my local University Extension Agent and found out that the levels of phosphorus at my site were completely within California norms – but off the charts compared to New England soils. I still send soil to UMass on occasion, but I’ve learned to interpret their reports through a California lens.

Read others’ reports. Soil analyses from other parties may provide some valuable additional information, depending on when they were generated. A geotechnical report may address grading, drainage, soil stability on slopes, presence of underground water, and other factors you might be unable to look at in your horticultural analysis.

Read others’ reports. Soil analyses from other parties may provide some valuable additional information, depending on when they were generated. A geotechnical report may address grading, drainage, soil stability on slopes, presence of underground water, and other factors you might be unable to look at in your horticultural analysis.

Most soil labs specialize in horticultural properties of soil and often, testing for pathogens. A different specialty lab will be needed to detect chemical contaminants. If the soil or water had ever been tested for contaminants, accessing that lab’s report would also be helpful.

USDA soil survey information is available online, although designed for use on Windows systems. SoilWeb apps can also be used to access soil survey data for most of the United States. PDFs of historical surveys are available although they do not include PDFs of the large color maps that came with the original printed versions, so they are less useful. Your regional USDA office may be able to get you a printed copy of any historical soil survey or you may find one at a USGS library or Federal Depository Library.

Hopefully, soil is the first thing you want to know about when designing a new landscape. But beware: the more you know about it, the more you realize how much more there is to know. You may just find yourself hooked on soil science.

Hopefully, soil is the first thing you want to know about when designing a new landscape. But beware: the more you know about it, the more you realize how much more there is to know. You may just find yourself hooked on soil science.

Ellyn Shea is a consulting arborist in San Francisco.

Leave Your Comment