Many trees purchased from nurseries may have significant defects that can reduce the useful life of the tree. This isn’t just speculation; there is good evidence that large segments of the nursery industry are supplying defective plants. Brian Kane at the Urban Tree Foundation and Ed Gilman at the University of Florida, both respected researchers in this field, have been observing and reporting on this trend for many years.

Poor branch structure, including co-dominant leaders, can create weak points in the canopy. To recognize these defects landscape architects need to understand the natural branching forms of the trees they specify so that they can detect when this form has been manipulated by the nursery, allowing them to pick healthy specimens. Hidden below the ground are equally deadly defects such as girdling roots and buried root collars, created during different phases of the production process, that can cause poor establishment or tree failure later in life. Combined, defects above and below the ground reduce the trees ability to establish and can cause decline or premature failure.

Crown defects have become so common that in some cases they are no longer seen as defects, but rather just the normal appearance of a particular species. Probably the best example of this is the Bradford pear. Pears were heavily used from the 1960’s to the 1990’s as a perfect street tree. They had symmetrical lollypop heads and grew well in difficult soil conditions. But these trees got the reputation of falling apart as they aged, splitting ‘like celery’ from a weak common branch point. This splitting problem isn’t endemic to the species; rather the weak branch points were created by the nursery making pruning cuts that enabled the production of the symmetrical crown. The pruning cuts resulted in multiple codominant branches growing just behind the cut, which were easy for the nursery to exploit into the perfect tree. Other species such as elm, maple and zelkova suffer from similar defects that weaken the tree long after planting. All of these species typically produce few co dominant branches in forest conditions.

This failed pear tree is the result of poor nursery pruning practices that created multiple co-dominant leaders.

These failed maple trees are the result of poor nursery propagation practices that created girdling roots. Photo: Patrick DeCoste

Over the past 15 years there has been significant research into these defects and how they can be managed. The nursery industry has been slow to correct the practices that create these defects, although the better nurseries are changing production methods. Nonetheless, for the foreseeable future, the burden to source good quality trees for projects will rest with the landscape architects who specify the trees, and nursery inspections will be a critical part of project quality control. The following is a primer that designers can use to create and enforce plant quality specifications.

Specifications

A good specification is the essential foundation for the inspection. They form the basis for acceptance or rejection at the nursery, and the instructions to the contractor to modify the plant stock to correct defects if acceptable plants cannot be sourced. While the following discussion is directed to trees, shrubs have similar sets of defects, particularly in their root stock, that need attention.

Fortunately, a good nursery stock specification already exists and its adoption is critical to obtain quality nursery stock. No, it is not the American Standard for Nursery Stock ANSI Z.60, which is mostly a measurement and term definition standard and makes very few statements about the actual quality of the tree. (It is still important to include ANSI Z.60 in a specification as it is needed for important industry references.) The document that must be included in the specification is the plant quality specification produced by the Urban Tree Foundation. Developed in 2014, it’s a specification template that designers can adapt to their project needs and gives them the tools to demand a different quality than is typically available. This is a complete set of specifications and includes plant quality details as well as plant installation and soil modification.

Client and contractor buy-in

Designers who claim interest in sustainable outcomes must include sustainable plants. Incorporation of these requirements into the plant procurement and installation process requires education of the client and the contractor.

The client must be informed of and agree to the higher standard early in the design process, as these higher plant quality standards will add cost to the project including slightly higher plant purchase and installation cost, as well as additional construction administration fees for the landscape architect. The benefit to the client will be more rapid establishment and trees with longer life expectancy and fewer management problems. It is understood that some clients may be only interested in initial project cost and/or may not care about plant quality. For that type of client there may be little value to forcing these ideas into the construction process. (More on contractor buy-in later on in this article.)

Plant pre-purchase

For larger projects, the option for plant pre-purchase offers the best opportunity to attain quality plants because it removes the pressure for quick acceptance and allows a selection of quality nurseries and negotiations to modify the plants during the pre-purchase contract period. If the project schedule affords one growing season in advanced of installation, significant pruning can be accomplished that can turn marginal stock into good quality stock. Below ground plant quality issues can be easily mitigated with time for the tree to adapt to any root loss.

Project submittals

Contractors typically submit proposed nurseries for approval. In an ideal situation, the designer will have included in the project documents a list of acceptable sources and made sure that the plants specified are available, but it cannot be assumed that even the best nurseries are producing defect-free trees. The new specifications should be the basis for acceptance during the inspection phase even at pre-approved nurseries.

Discussions with the contractor and the proposed nurseries can set the stage for a successful inspection phase. Reviewing the requirements with the contractor and the nursery ahead of time, including the root collar inspection requirement, will improve the dialogue.

Establish that the grower understands that this is not a typical plant tagging exercise and that that you are using a non-standard specification. Explain that for field-grown material the inspection must occur prior to digging. If trees are already dug, your options to inspect and impose modification to the root ball become very limited.

Be prepared for resistance; you will need your client’s support at this critical point in the process. Be proactive and start early in the construction sequence to give time for these inspections. As soon as the installing contractor is identified, reach out to them to start the process. If you wait for the submittal to arrive, it may be too late.

Preparing for the inspection

Preparing for the inspection means being educated about the plants you are selecting and having the tools to conduct a thorough evaluation.

Understand the juvenile and ultimate forms of the plants that you are inspecting. It is surprising how few designers understand the difference and importance of permanent future branches and temporary branches. For species that mature into large trees with tall, clear trunks, most if not all the lower branches are temporary and the ultimate canopy branching form of the tree may not actually exist. Opposite branching species will have different and more difficult branch management issues than alternate branching species as they mature. Review Structural Pruning: A Guide for the Green Industry by Gilman, Kempf, Matheny and Clark to understand properly pruned young trees.

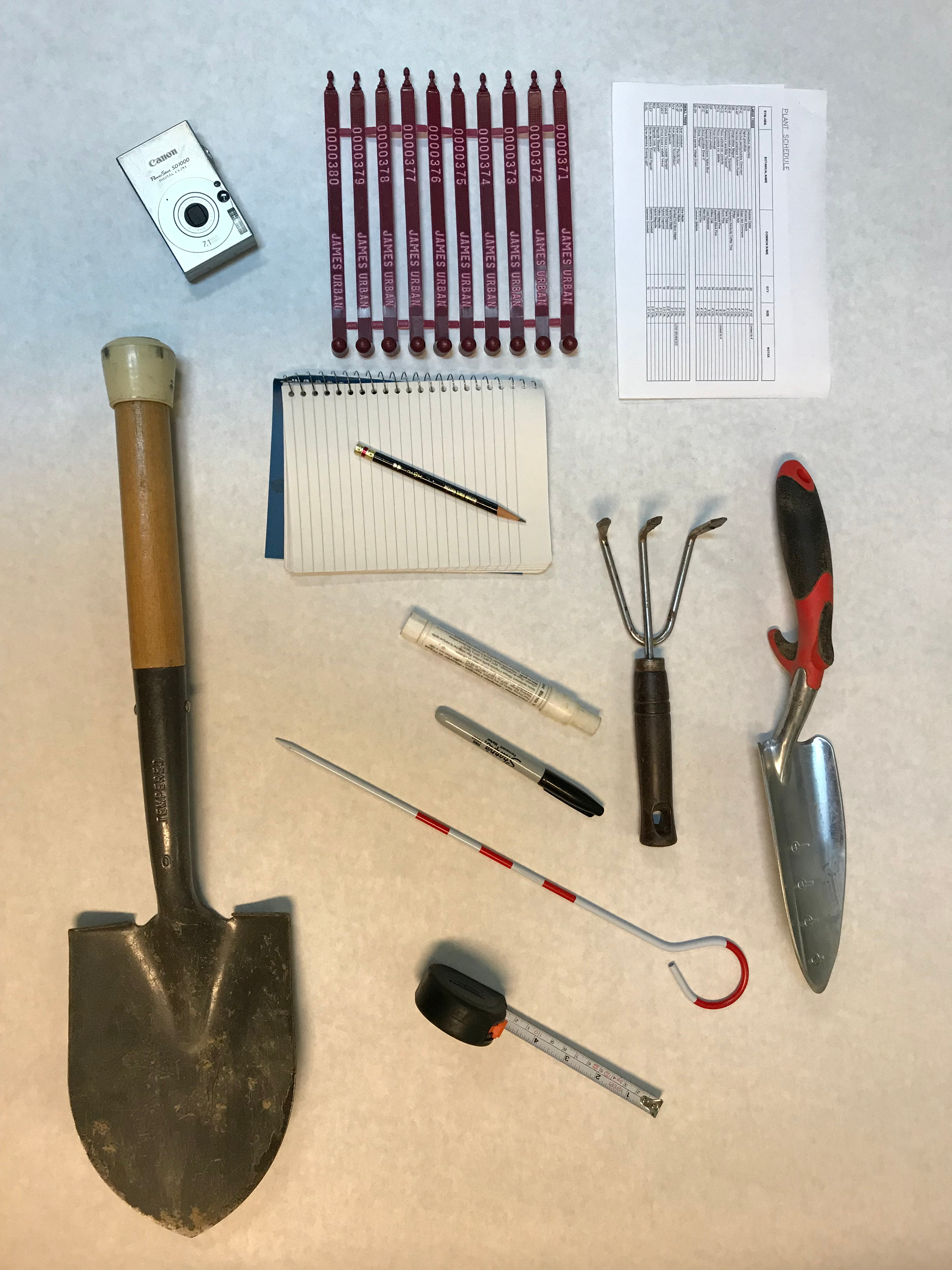

You’ll want to bring your own tools for the inspection. These must include:

- Forked hand cultivator and a hand trowel (available at garden stores)

- Surveyor’s chain pin (available at benmeadows.com)

- Small tape measure (preferably one that has linear units on one side and diameter units on the other; available at benmeadows.com).

- White and black grease crayons (available at art stores) or a yellow lumber crayon

- Sharpie marker

- Small notepad

- #2 pencil (they write on wet paper better than pens)

- Camera (your phone)

- Plant list and plant quality specification

- Your office’s numbered plant seals

If getting specific trees in certain places is important, a reduced copy of the planting plans will allow tree numbers to be assigned to specific locations. Bring the plant quality section of the specification and any other documentation on plant quality requirements. Dress to spend time in the dirt on your knees and walking thru wet grass. Don’t forget sunscreen, insect repellent, and a hat.

Inspection day

Keep the discussion friendly and light, but be firm with explaining that you will be doing invasive inspections of the root collar. For many nurseries this will be a new experience. Allow a generous amount of time and be sure the grower is prepared to work with you through the process. The inspection time per tree for this process is going to take, at a minimum, twice as long as a more typical nursery inspection. Take good notes and lots of photos.

Nursery inspection trips are a critical part of a designer’s ongoing education. Be sure to look at other trees and plants available in the nursery. A block of really wonderful trees not on your list can stimulate design ideas for future projects. Nursery owners love it when you ask “what are those trees” or “can we stop here for a closer look”. Make the day a learning experience.

Inspection above the ground

One of the most important things to recognize is that the trees that meet the specification will likely not have a perfect shape.

It is unfortunate that many designers approve trees that they think “look good” without understanding that the very attributes that make a young tree attractive at a young age may be the same features that cause a tree to be defective later in life. Landscape architects must understand basic tree defects and the long-term growth habits of the trees they specify.

The inspection of trunks and canopies will be similar to previous inspections, except you will be looking for different items. Young tree branch structure is almost never similar to the mature tree structure. Branch spacing in nursery-produced trees is typically much closer together than naturally growing trees due to previous pruning. Trunk flares will be harder to distinguish. For trees smaller than about 4 inches (10 cm) in caliper many if not all of the branches on the tree when purchased are likely to need to be removed as the tree matures.

The new pruning approach will create a more open canopy, and the tree may not present the most dramatic image at the time of planting. Force yourself to select trees with branching that will result in a central leader or that can easily be pruned to have one. Most trees will require some additional pruning (and in some cases significant pruning) to meet these standards. However, trees produced by good growers will typically require minimum additional work.

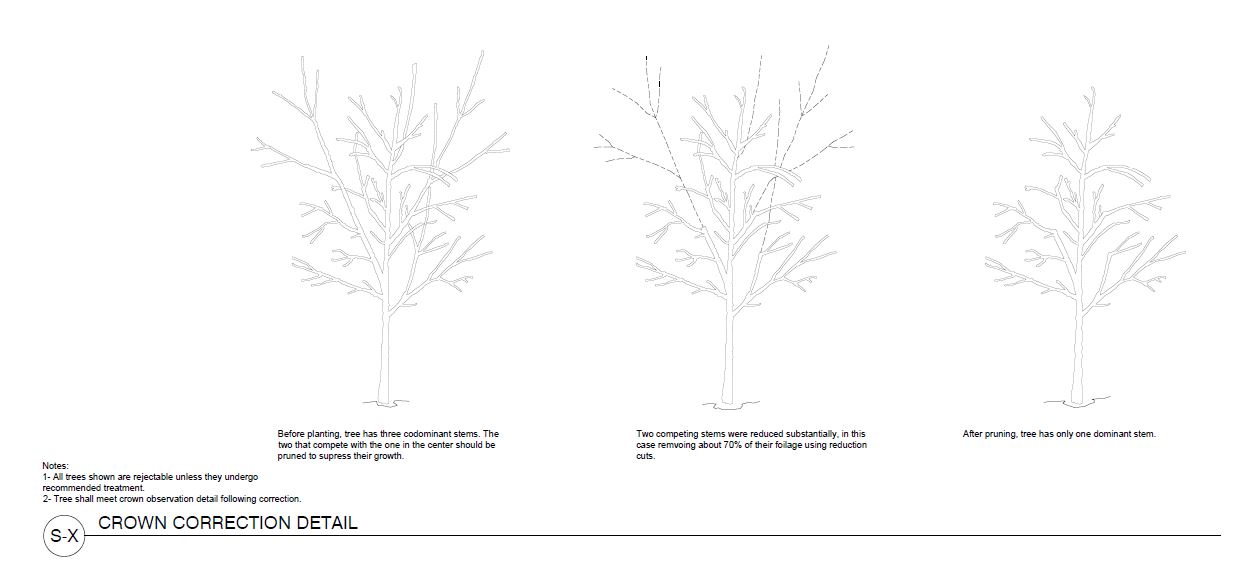

The most common defect in trees results from the grower making a heading cut at the top of the liner early in the growing process to create multiple branches (called codominant leaders) growing from a single point. This creates the dense symmetrical canopy often desired by designers. Leaving co-dominant branches is a significant cause of future branch failure. Determine if some of these leaders can be removed, what kind of a single leader tree would result, and at what impact to future tree shape. A double leader tree can almost always be fixed with only a small kink in the trunk. This kink will slowly straighten as the tree grows.

Three branches from the same location can be repaired but with more impact. One or two of the leaders might be partially cut back or reduced rather than immediately removing them at the main stem. Reducing a co-dominant stem (removing about one half to one third of the stem length) slows down the growth of this limb while encouraging the growth of the remaining leader. But this approach requires a second round of pruning two to three years after planting to make a final branch removal cut. This option passes on the problem to a future unknown tree manager who may not be attuned to the branch management process. Four or more leaders from the same point becomes very problematic and rejection is likely the better option. For trees like zelkova there may not be many nursery trees that are suitable.

Tree with many co-dominant leaders developing from a nursery pruning cut to create a full head. This tree should be replaced.

Special cases

What if a ‘character tree’ is desired? Meandering trunks and branching are not structural defects provided that long term structure impact is understood. A double leader tree with a wide branch angle of 90 degrees or more may produce a tree with strong structure well into the future. The branches should have a pronounced ‘U’ shape at the branch union rather than a tight ‘V’ shape. Nurseries are happy to sell what others consider a cull.

Evaluating minor defects

Minor defects such as unhealed pruning cuts, broken branches, and bark abrasions may not be as serious as they appear. They may typically heal and be acceptable. Significant wounds at the base of the tree may be more critical than a similar size wound higher in the canopy. A tree with good branch structure but minor bark damage is preferable to a tree with many co-dominant leaders but no other defects.

If there is an option to select trees from a block that are slightly under the specified size but have superior structure, take them. Adherence to the specified size is likely the least critical factor to long term project success. Be flexible about substituting cultivars and even species if you chance on a set of really good trees after rejecting an unacceptable offering.

Diseases, damage, and splitting

Bark diseases, borer damage, and significant bark splitting is a set of conditions that should be noted and is likely a cause for rejection. Designers must develop a knowledge of different types of insects and diseases that affect the types of plants being specified in order to identify affected plants.

Small trunk wound that is healing and may not be cause for rejection if the rest of the tree is acceptable.

This does not mean you need the proficiency of a plant pathologist or entomologist. You do not need, for example, to be able to identify a particular canker or insect, but you should be familiar with the basic expressions of insect damage, cankers or fungus infestation in nursery stock. Simply knowing the normal color and texture of a particular species’ bark and leaves should be sufficient to identify when something is irregular. You can always note that something does not look correct and check resources when you get back to the office. Good growers will explain what you are seeing and can be trusted to be give honest explanations. Asking what they think that reddish patch on the bark is will help them to respect you as an interested professional.

Conclusion

The above recommendations are counter to the approach most designers take in the nursery. It requires rethinking our natural inclination to select trees that look best on opening day – but may have long-term problems – rather than looking for trees with more open, and often less symmetrical, structures that are more sustainable and have greater longevity.

Inspections of the root system and depth of the trunk flare are equally important, and more complicated. Instructions for how to carefully select nursery trees after a belowground evaluation will be covered in the second half of this series.

James Urban, FASLA, is an expert in urban trees and soils. He is the author or the book Up By Roots: Healthy Trees and Soils in the Built Environment.

Top image: Herry Lawford / CC BY 2.0

Leave Your Comment