Trees and sidewalks transform city streets into lush and inviting places to linger, to chat with a neighbor or enjoy the outdoors on a summer evening. As key pieces of urban infrastructure, they each invigorate a city in their subtle ways. Both provide health and economic benefits, and help to build character and support a sense of place and community. Each comprises a valuable public asset. Yet these two elements in our public streetscapes are often at odds with each other, with tree roots causing damage to sidewalks, and sidewalks or other pavement inhibiting tree health and longevity by limiting root development space and water or nutrient availability for trees.

While conflicts between roots and sidewalks can sometimes feel intractable, quite a number of potential solutions exist for minimizing and even eliminating the issues. To be effective and successful at reducing tree and sidewalk conflicts on a comprehensive scale, cities should act on several levels. In this article, we’ll discuss strategies within four broad categories that can be used by local or regional governments:

- Policies (to guide the management of trees and sidewalks, including both new construction and repair/maintenance)

- Processes (to establish clear expectations and actions within government and those tasked with oversight of trees and sidewalks)

- Standards and tools (for new construction and repair)

- Funding

When sidewalks become impassible, or trees fail to thrive, their tremendous value to our community is dramatically reduced and – in some cases – lost altogether. It is in a city’s best interest to create a clear and progressive plan for managing the health of their trees and their sidewalks in order to maintain these assets. Here are some guidelines for doing that.

Policies

The responsibility for maintaining trees and sidewalks is typically determined by each city or other jurisdiction, and can vary widely. Some cities place the full responsibility for upkeep of street trees and/or sidewalks with the adjacent property owner, while others take on the maintenance of street trees (such as in Boulder, CO), sidewalks (such as in Bellevue, WA) or both. Many jurisdictions fall somewhere in between. Some cities, such as Chicago, IL and Boulder, CO provide a cost-sharing program for sidewalk repairs. A City’s policies for managing street trees and sidewalks provide key guidance in how these vital elements of public infrastructure are managed.

Some of the main policies and rules that may help in guiding management of trees and sidewalks include:

- Tree Ordinance: Whether specific to street trees, or addressing trees on private land as well, a clear tree ordinance should help guide how to protect and preserve existing trees, and when, where, and how to plant new ones.

- Urban Forest Management Plan: Some cities go a step beyond a tree ordinance and create a comprehensive plan to manage the city’s trees. These commonly address trees on both public and private land. An urban forest management plan will likely tie in to other planning efforts, such as growth management, stormwater planning, or other development planning.

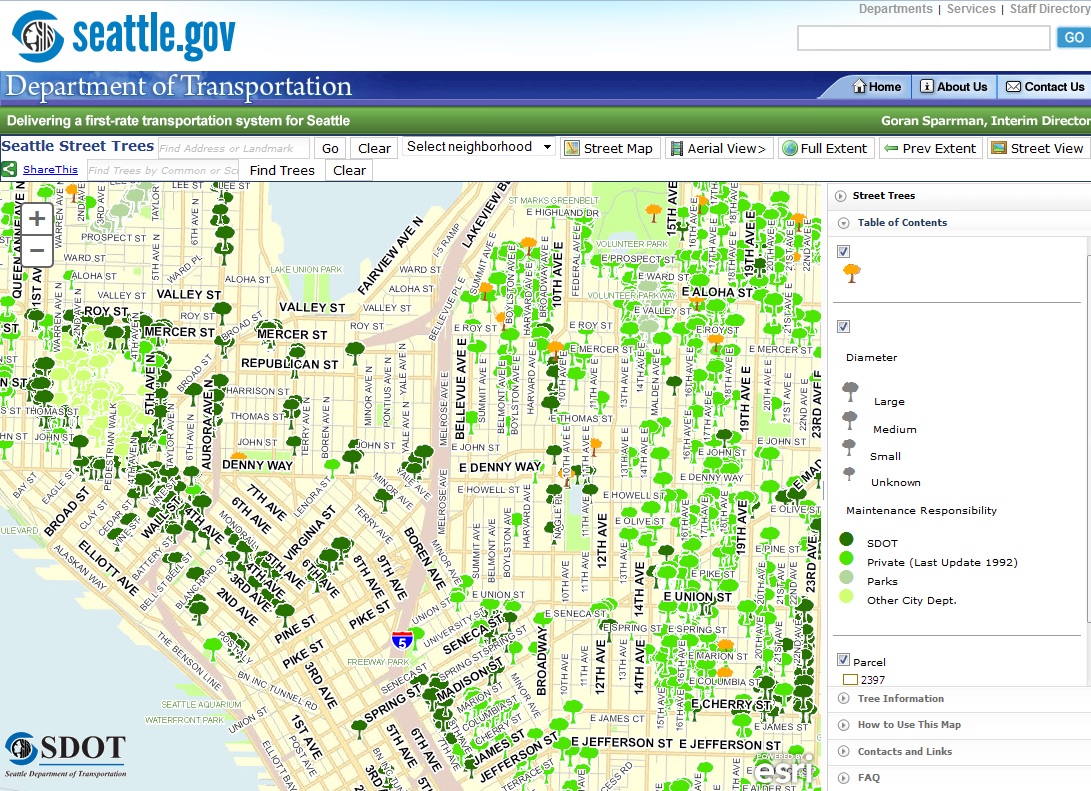

- Street Tree Inventory: Developing a street tree inventory and map (with potential inclusion of trees in parks or other areas) with details such as species, size (DBH), and ownership/ maintenance responsibility can be helpful in management and planning for the urban forest. Such an inventory can also be maintained as a public map available on the web (see examples from New York City, Seattle, or San Francisco), to facilitate public involvement in maintenance and stewardship.

- Street Tree List: Often incorporated into or referenced by a tree ordinance, many cities have developed a list of approved street tree species/cultivars. Such lists should address the situations/settings for which each tree is approved (e.g. shorter trees for under power lines, or minimum planting area widths for larger trees, etc.). Species listed should be appropriate to the region’s climate as well as use in the urban environment, be vetted for likely pest or disease problems, and be selected to help provide the necessary diversity within the urban forest.

- ADA Transition Plan or other mobility planning: Many U.S. cities have developed or are developing plans to work towards more complete compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), or more specifically the Proposed Guidelines for Pedestrian Facilities in the Public Right-of-Way (aka PROWAG). These plans may help guide repair to or development of new sidewalks, curb ramps, and other pedestrian facilities.

- Street Tree and Sidewalk Design Requirements: These are often established both by zoning code (setting unique requirements for different types of development) as well as standard plans or specifications. The design requirements may include sidewalk material options (including base courses or subgrade materials), widths for both sidewalks and planting areas, utility or other setbacks and clearances, tree types, and spacing (referring also to an approved street tree list).

One particularly noteworthy policy or standard for developing a healthy urban forest and reducing tree and sidewalk conflicts is establishing a minimum planting area and/or minimum soil volume per tree. In the past, minimum spaces for tree planting have typically been expressed in terms of surface area, whether as a minimum width for a planting strip between curb and sidewalk, or simply minimum length and width for a tree pit. Many cities have such standards on the books.

However, recent research – as well as the practical experience of cities leading in this effort – has shown that these practices may have allotted spaces that are too small for trees to thrive in without damaging adjacent sidewalks and infrastructure. In addition, experts and researchers in the field have more recently begun looking at usable soil volume as a better measure of a tree’s needs than strictly surface area. This is helpful in part because usable soil volume can not only help ensure that a tree actually has what it needs to thrive, but can be a more flexible requirement among competing needs for urban space. In some cases, using solutions such as some of those mentioned under the “Standards and Tools” section below, useable soil for trees may be provided below pavements, giving options to develop healthy urban trees while still providing sidewalks, gathering spaces or other urban amenities within limited space.

Recommended soil volumes by tree size have been presented by various researchers and professionals over the past decade, ranging from 400 to 600 cubic feet for a small tree to 1,500 to 4,000 cubic feet for large trees. Some jurisdictions have adopted minimum soil volume requirements, including Washington, DC, Denver, CO and Athens, GA. While some of the requirements that cities have enacted are lower than the volumes recommended by tree professionals, having these in place is a useful step in ensuring that trees have a minimum amount of soil to help them thrive while helping to reduce conflicts with sidewalks. Once soil volume is established as a metric for tree planting standards, it would likely be easier for a city to adjust its minimum volumes as their particular experience warrants.

Process

Cities should have processes in place to implement their policies and standards, including review of new construction and repairs of trees and sidewalk infrastructure, whether these are undertaken by a public agency or private entities. There are a number of questions to ask in terms of process when looking at how tree and sidewalk conflicts may be resolved or avoided within a given jurisdiction. Are trees and sidewalks managed and overseen within the same department? Who reviews applications and designs for new development or repairs? Who reviews field conditions, and inspects work along public streets?

Some cities include the divisions and staff that manage sidewalks and street or other public trees within the same department – typically either their transportation or public works departments. Cities that combine street tree management in the same department with other street management include Washington, DC (in DDOT), Los Angeles (Bureau of Street Services), Pittsburgh (Public Works) and Seattle (SDOT). This facilitates staff from forestry and roadway engineering and repair working together in review of solutions and identifying supporting budgets relating to trees and sidewalks.

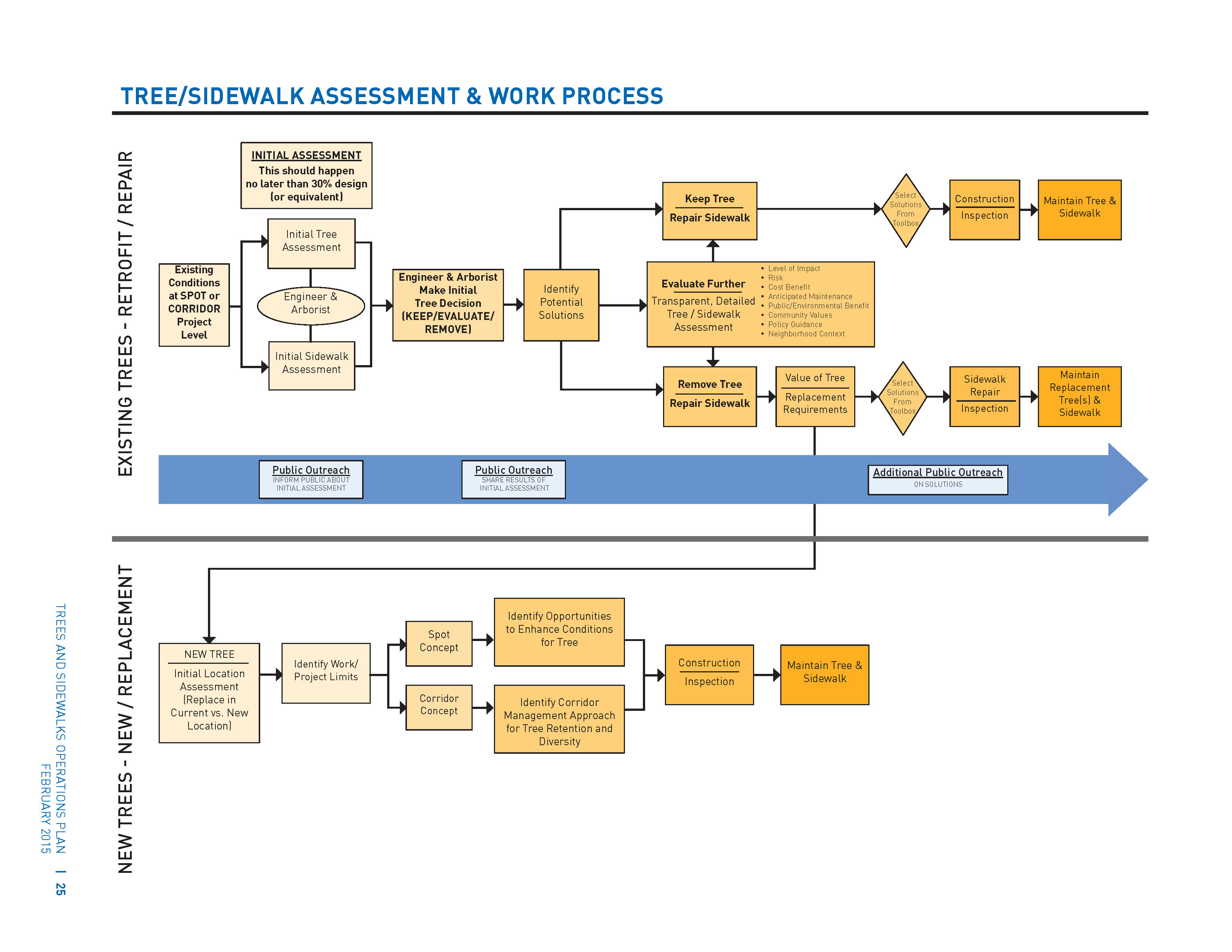

Seattle, in fact, has formalized a process under its Trees and Sidewalks Operations Plan (approved in 2015) in which both an arborist and an engineer perform a joint field review of tree and sidewalk conflicts that need to be addressed and make initial recommendations for repairs. In developing this operations plan, Seattle was seeking, among other things, a way to improve efficiency and tree preservation under its sidewalk repair program. In some cases, projects were prolonged when pavement design and tree preservation decisions were made after work had begun and existing sidewalk pavements removed.

By involving both an arborist and an engineer early in the process, city staff have been able to make key decisions sooner, looking at tree health (and value and feasibility of preservation versus removal/replacement) and discussing potential tools for use in making repairs. The City has a brief form that is used to document the joint field review and help guide further action. This helps to ensure that trees are not unnecessarily removed, while considering a range of solutions for repairing and providing accessibility along the City’s sidewalks.

An excerpt from the Seattle Department of Transportation’s Field Arborist Engineer Review Checklist (page 23)

Standards and Tools

There is a wide range of tools now available to help prevent or repair conflicts between trees and sidewalks. The basic solutions available, or at least approved for use in a given city, are often outlined in the policies and design standards of the jurisdiction. Many jurisdictions are looking to promote urban tree health and may consider additional solutions if proposed by those doing work along the street, especially if they result in sidewalks and planting strips with reduced maintenance needs.

A helpful compendium of potential solutions to tree and sidewalk conflicts was written by authors Laurence R. Costello and Katherine S. Jones, titled “Reducing Infrastructure Damage by Tree Roots” and published by the Western Chapter of the International Society of Arboriculture (WCISA) in 2003.

The Toolkit chapter (pg 31) of the City of Seattle’s Trees and Sidewalks Operations Plan also provides a broad range of tools and solutions divided into four categories:

- Paving and other surface materials

- Rootzone-based materials

- Infrastructure-based design solutions

- Tree-based solutions

The toolkit further indicates which solutions might be applied in new construction, repair/retrofit situations, or either, as well as giving a relative cost range for the various tools.

For example, the “Paving and other surface materials” section addresses the use of pavers. Unit pavers (including new rubber or composite varieties) provide a more flexible surface, resisting the cracking commonly seen with concrete sidewalks, and may be reset more easily if upheaval becomes a problem. Rootzone-based materials include basics such as mulch or root barriers, as well as more involved tools such as providing root paths to help direct roots and focus their growth in desired locations.

Infrastructure-based design solutions are often addressed in a city’s design standards, and focus primarily on giving trees adequate space to grow, and potentially using more robust paving approaches to avoid sidewalk damage. These tools include practical items such as a curving or offset sidewalk, tree pit sizing, and curb bulbs, to give trees more space to grow. They also include soil volume, a key element in ensuring successful tree development and reducing damage to sidewalks and other nearby infrastructure. The tree-based solutions includes pruning (both crown and root) but the key item is the development of an approved street tree list to help select an appropriate tree for a given location.

Other cities, such as Portland, OR have developed similar and in some cases more pared-down toolkits of solutions.

Funding

A final, key piece to addressing tree and sidewalk conflicts is funding. As discussed above, cities take various approaches to who is required to pay for repairs to or replacement of damaged sidewalks and street trees. Some broad categories of funding that are necessary to maintain healthy street trees and a sidewalk network in good, accessible condition include:

- Tree planting (and potentially maintenance)

- Inspection and enforcement of tree planting, maintenance, and protection

- Sidewalk repair

Regardless of who pays for the implementation, a City should have at a minimum a clear and established process and funding for management and oversight of its tree and sidewalk programs. There need to be adequate staff to ensure that design and construction requirements are being met, otherwise the city may continue to suffer challenges in developing its street trees and urban forest, and a continued or growing backlog of sidewalk repair needs. Efforts to secure this funding may hinge, at least in part, on demonstrating and convincing city executives, policy makers, and the public of the value and broad range of benefits that healthy street trees and a robust, well-maintained sidewalk system provide.

Concluding thoughts

Addressing tree and sidewalk conflicts, and establishing a healthy urban forest together with a sidewalk network in good condition at a city-wide scale takes a multifaceted approach. Some of the key areas that should be addressed include establishing policies that guide the maintenance and development of trees and sidewalks, processes for implementing these policies, and a preferred set of tools to be used in accomplishing the work. Last but not least, cities must make sure there is adequate funding to address the work needed, whether it is simply oversight and management of work done by private entities, or funding the work associated with repair or replacement of sidewalks, and installing new street trees with appropriate space and materials.

Some of the innovative elements we’ve discussed in this article for developing healthy street trees alongside high quality sidewalks include providing an online street tree map and database (and keeping it reasonably up to date); providing standard minimum tree planting space dimensions and (ideally) minimum soil volumes; and encouraging collaboration by engineers and arborists early in the process of sidewalk repairs and construction adjacent to street trees. Utilizing some or all of these techniques in working towards development of processes, policies, tools and funding will help to establish a successful program to develop and maintain trees and sidewalks throughout a city.

Justin Martin is a landscape architect at MIG | SvR in Seattle, WA.

Leave Your Comment