Public space is more than just a pleasant amenity in our towns and cities, it is an important connection between our homes, businesses, institutions, and the rest of the world. It’s where we bump into each other and wave hello. It’s also where nearly half of violent crimes happen (Bureau of Justice Statistics), where people run into law enforcement, where we protest and demonstrate. Public space is for announcing our outrage and expressing out highest aspirations, while simultaneously encompassing the most banal (and essential) utilities and infrastructure. In recent years, the importance of public space has grown in the eye of planners, designers, and the public, and the concept of “placemaking” has come to the forefront of many urban centers.

Placemaking is a people-centered approach to the planning, design, and management of public spaces. It involves looking at, listening to, and asking questions of the people who live, work, and play in a particular community to discover their needs and aspirations. This information is then used to create a common vision for that place. Small-scale, simple improvements result from this vision that can immediately bring benefits to public spaces and the people who use them.

Places that fulfill these visions are the greatest expressions of thoughtful design. And they need not be grand in scale or scope in order to be great. The Project for Public Spaces (PPS), a non-profit promoting placemaking, asserts that most great places, whether a grand downtown plaza or humble neighborhood park, share four key attributes:

- They are accessible and well connected to other important places in the area.

- They are comfortable and project a good image.

- They attract people to participate in activities there.

- They are sociable environments in which people want to gather and visit again and again.

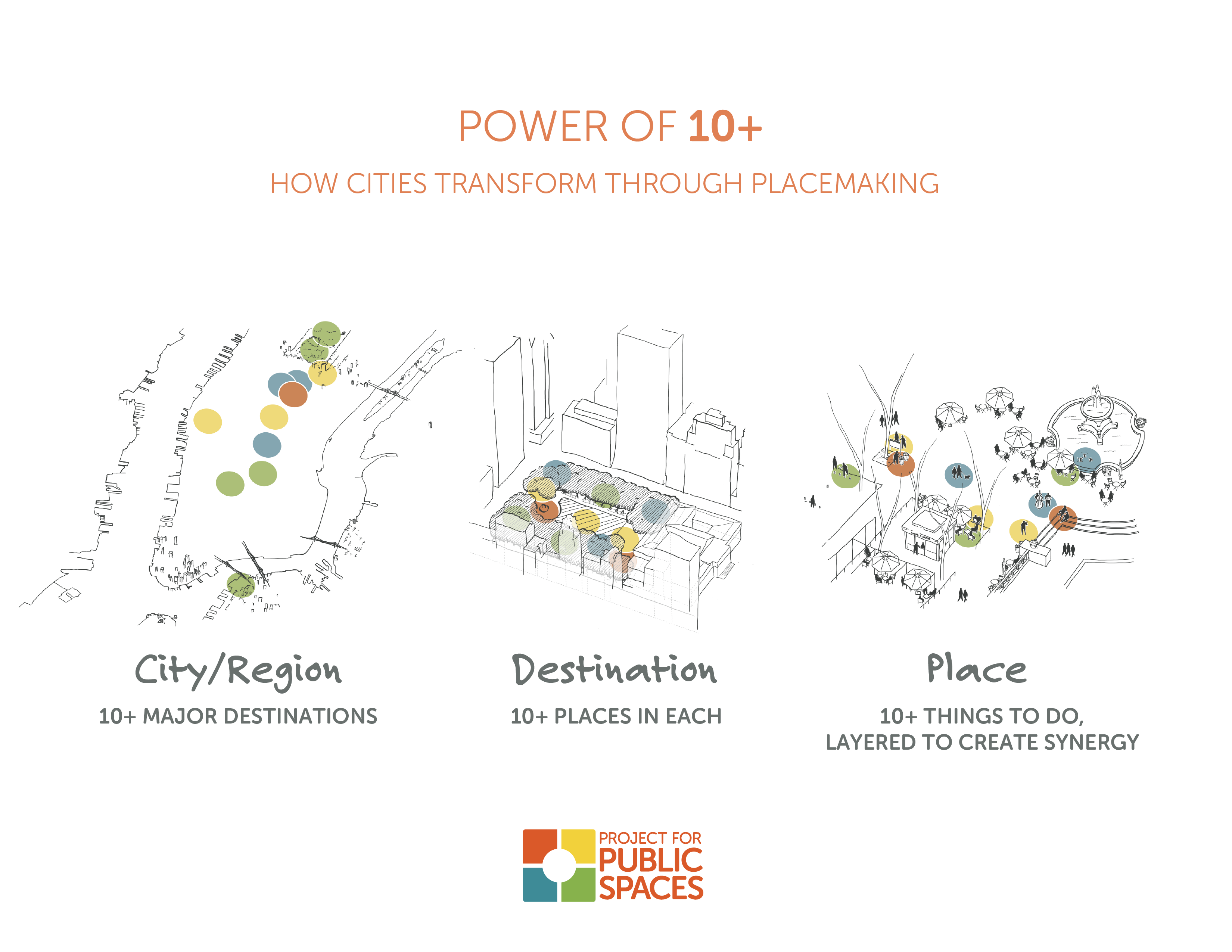

PPS also describes a philosophy of “The Power of 10+” – the notion that cities of all sizes should have at least 10 destinations where people want to be in order to attract new residents, businesses, and investment, as well as the people who already live there. A destination could be a downtown square, a main street, a waterfront, a park, or a museum. That place, in turn, should have 10 places in it. As an example, a public square could offer: a café, a children’s play area, a place to read the paper or drink a cup of coffee, a place to sit, somewhere to meet friends, and so forth. Within each of the places, there should be at least 10 things to do: walk a dog, play in a fountain, get lunch, feed the birds, etc. By layering destinations, places, and activities, complex spaces are created that will draw a wide range of people to an area.

They have eleven “Principles for Creating Great Community Places” for people who are involved in design and other disciplines related to placemaking to refer to.

The community is the expert

This is a hard one for many designers, who may have good intentions about incorporating community identity and preferences, but also their own notions about what constitutes “good” design. Tap into the community for information about how the area functions, historical perspective, critical issues, and public feelings. This creates a sense of community ownership in the project.

Create a place, not a design

Designers should strive to create a place that has both a strong sense of community, a comfortable image, and activities/uses that collectively add up to something more than the sum of its (often simple) parts.

Look for partners

Partners are critical to the image of a public space improvement project – and its future success. They can be local institutions, museums, schools, or others. These collaborations are important for providing support, community involvement, and getting a project off the ground.

They always say, “It can’t be done.”

In creating good public spaces, those involved inevitably encounter obstacles. Often, this is because no one in either the public or private sectors has the job or responsibility to “create places.” Starting with small-scale improvements can demonstrate the importance of “places” and help to overcome the objections that will necessarily come.

You can see a lot just by observing

Observations help uncover what kinds of activities are missing in a space, and what might be incorporated in the future. Once spaces are built, continuing to observe them teaches us even more about how they evolve and can be managed.

Have a vision

Visions are individual to each community, however some basic ideas are useful to consider in nearly all of them: the kinds of activities might be happening in the space, that the space should be comfortable and have a good image, and that it should be an important place where people want to be. That is, that it should instill a sense of pride in the people who live and work in the surrounding area.

Form supports function

Input from the community and potential partners, understanding how other spaces function, and overcoming obstacles and naysayers will shape the space. While design is important, these other elements tell you what “form” you need to accomplish the vision of the space.

Triangulate

“Triangulation is the process by which some external stimulus provides a linkage between people and prompts strangers to talk to other strangers as if they knew each other” (Holly Whyte). For example, if a bench, a wastebasket and a telephone are placed with no connection to each other, each may receive a very limited use, but when they are arranged together along with other amenities such as a coffee cart, they will naturally bring people together.

Experiment: Lighter, quicker, cheaper

The best spaces experiment with short-term improvements that can be tested and refined over many years. Seating, outdoor cafes, public art, striping of crosswalks and pedestrian havens, community gardens, and murals are examples of improvements that can be accomplished in a short time and at little expense.

Money is not the issue

Once you’ve put in the basic infrastructure of the public space, the vendors, cafes, flowers, and seating will not be expensive. It is these elements that will make the space “work.” Additionally, if the community and other partners are involved in programming and other activities, this can also reduce costs. By taking a “people first” approach to your decisions and design, the community is likelier to have enthusiasm for the project — and benefits will be more readily visible relative to the cost.

You are never finished

Good public spaces respond to the needs, opinions, and ongoing changes of the community. Being open to change and having the management flexibility to enact that change is what builds great public spaces and keeps them great.

The movement to bring thoughtful, people-centric design to cities and towns – to make places that are not only functional, but meaningful – is growing. There is increasing recognition within the design and planning disciplines of the value of creating places that we care about, that we invest in, places where we want to live. As a landscape architect, I’m incredibly excited about incorporating these concepts into my work. What kinds of rich, thriving communities can we create with this approach? I can’t wait to find out.

Works Cited

Project for Public Spaces

Placemaking Chicago

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Nicole Peterson is a landscape architect with the Kestrel Design Group.

Leave Your Comment